This Parish Summary is an overview of the large amount of information held for the parish, and only selected examples of sites and finds in each period are given. It has been beyond the scope of the project to carry out detailed research into the historical background, documents, maps or other sources, but we hope that the Parish Summaries will encourage users to refer to the detailed records, and to consult the bibliographical sources referred to below. Feedback and any corrections are welcomed by email to heritage@norfolk.gov.uk

The parish of Quidenham is situated in the Breckland district of Norfolk, 10 miles northeast of Thetford and 24 miles southwest of Norwich. It borders Attleborough to the north and Harling and Kenninghall to the south. The name Quidenham may derive from the Old English phrase meaning ‘Cwida’s homestead’. However, other evidence suggests an individual named Guy or Guido held the land here in 1000, with the modern name being a modification of ‘Guidenham’. Whatever the case it is certain that the parish has a long history and was well established by the time of the Norman Conquest, with its population, land ownership and productive resources being detailed in the Domesday Book of 1086. Nowadays Quidenham village is a quiet, rural place but is known throughout East Anglia for its two splendid institutions, the Carmelite convent and the Children's Hospice.

Over the years this parish has been the subject of a great deal of archaeological activity, particularly in the form of metal detection and field survey. As a consequence a collection of over 300 artefacts, sites and listed buildings have been recorded. Therefore the following summary can only aim to highlight a small selection of the many fascinating discoveries and features from the area. It is heartily recommended that any interested readers should access some of the individual records to delve deeper into the heritage of Quidenham.

Many of the prehistoric finds and sites that are noted in the area were uncovered by extensive fieldwalking in Hargham (see further reading) and a high number of finds date to this period. Possible traces of occupation and resource exploitation in the landscape are registered through the large number of pot boiler sites (e.g. NHER 9210, 9162 and 39870) and features like hearths (NHER 6005). The locations of these scatters are undoubtedly linked to the collection and manufacture of flint implements. Indeed, the earliest recorded artefacts dating to the Palaeolithic period consist of flint tools such as axes (NHER 24145) and blades (NHER 13702). Similarly the next clearly represented period, the Mesolithic, has more of the same with blades (NHER 22771) and worked flints (NHER 40662) turning up. As is common with many areas of Norfolk the majority of prehistoric come from the Neolithic era. Large quantities of ubiquitous flint axes (e.g. NHER 9144, 9147 and 9148), scrapers (e.g. NHER 14859 and 16475), axe hammers (NHER 9091), hammerstones (NHER 13701 and 14038) and flakes (NHER 24144 and 32254) have been discovered in the parish. Unfortunately a large proportion of finds from the prehistoric period cannot be categorized into more specific eras, but these flint finds which include knives (NHER 29944 and 30835), production remnants (NHER 16475 and 29300) and tools (NHER 9145 and 24143) are still important. Thus our overall picture of Quidenham at this point in time is of a widely explored and occupied landscape.

Bronze Age monuments in Quidenham take the form of round barrows and hearths. Most of these hearths (NHER 10806-10809, 10812 and 10813) are not visible now necessitating a reliance on documentary evidence to discover their potential locations and existence. Others, like the one on Overa Heath (NHER 6004), survive into modernity and yielded pottery sherds and flints when investigated (NHER 10810 and 10811). A couple of the barrows were excavated in the early 20th century and were found to contain inhumations (NHER 6006 and 9154) while others held flints (NHER 10790) or pottery vessels of a contemporary date (NHER 10833). Agricultural ploughing has damaged many of these mounds like the one on Wilby Warren (NHER 9207) and the example recorded on land near to Eccles Hall (NHER 10787). Looking at the records it seems that barrows were built on nearly all the areas of heathland and grassland in the parish. In addition to these monuments various Bronze Age implements have been unearthed, including palstaves (NHER 10784 and 29885), a socketed axehead (NHER 39286) and agricultural tools: an adze (NHER 30730) and awl (NHER 31410). If all the documented barrow and hearth sites did exist during the Bronze Age then it would appear that there was a continuation of the high level of activity that seems obvious in earlier times. Doubtlessly metal detecting will help to add to the moderate collection of Bronze Age artefacts we have.

In spite of local legend, Boudicca the queen of the Iron Age Iceni tribe was probably not buried in Quidenham. Her burial in the so-called ‘Viking’s Mound’ (The Bubberies) (NHER 10785) is incorrect, as extensive study of the monument has determined it to be the motte of a Norman castle not a burial barrow. This leaves only one genuine Iron Age site in the parish, the earthworks of a possible dwelling to the south of Stacksford (NHER 9209). An assortment of contemporary artefacts have been unearthed through metal detecting, with silver Iceni coins (NHER 19544, 31404 and 32305), a La Tene type brooch (NHER 29888), tiny terret (NHER 30383) and clothing toggles (NHER 35174) forming just a small selection of what has been found.

As we move into the Roman period there are a huge number of reported finds, with far too many coins and sherds of samian or Romano-British grey ware pottery to mention individually. The same is true of brooches with Hod Hill (NHER 30362), Colchester (NHER 30378) and Dolphin (NHER 36100) types amongst the many identifiable examples from Quidenham. Everything from tweezers (NHER 37284) and nail cleaners (NHER 29885), used for personal grooming, to seal boxes (NHER 18644), for correspondence, and sarcophagi fragments (NHER 30348), from burials, have been discovered. Some of the objects from this period are quite beautiful, like the leaf-shaped escutcheon (NHER 30382) for the handle of a bucket or vessel that was found to the north of the New Eccles Hall School. This diversity of artefacts certainly shows significant activity during the Roman period – perhaps relating to occupation, trade, transport or manufacturing. Sadly no Roman sites have yet been discovered, although a Roman road (NHER 10816) was depicted running through the parish on a map of 1928. Of course, studying the location and concentration of artefact scatters may aid this search.

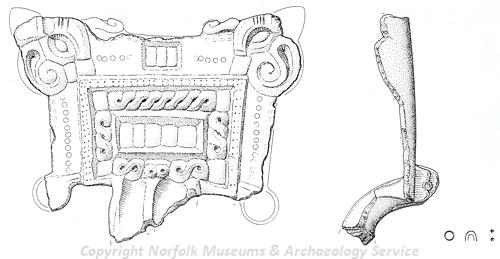

An Early Saxon upper bow and headplate of a great square-headed brooch from Quidenham Early Saxon cemetery. (© NCC)

The most obvious reminder of Quidenham’s Saxon heritage is the splendid flint round tower of St Andrew’s Church (NHER

10793), one of 124 round-towered churches in Norfolk. No Saxon burials have been recorded from the churchyard here but in 1859 antiquarians recorded the presence of 20-30 burial urns from an unspecified field in the parish (NHER

9158). It was suggested that these formed part of an Early Saxon cremation cemetery but the urns themselves have been lost and the find spot remains a mystery. Another cemetery site (NHER

37284) from this period has been postulated in the centre of Quidenham Park due to the number of brooches that were recovered. Excavations at the so-called ‘Shrunken Village’ site in Wilby (NHER

29582) show it was first occupied during Saxon times. The success of this first settlement no doubt stimulated the increased habitation here during the medieval period, with the substantial complex of enclosures from this period visible on aerial photographs. As regards to artefacts, some of the finest items retrieved from Quidenham are Saxon in origin. The best objects were found north of the Carr, and took the form of an unusual Early Saxon wrist clasp (NHER

30365) of unusual form and a superb fish-shaped mount from a hanging bowl of the same date (NHER

30365). Other items range from ornamental, like the stylised animal-head dress accessory (NHER

19544) and nice small-long brooch (NHER

30092), to the mundane – pins (NHER

30367 and

30375), strap end (NHER

29450) and sherds of Ipswich Ware (NHER

31315) and Thetford Ware (NHER

34974) pottery.

The medieval monuments of Quidenham can be summarised as churches, roadside crosses and deserted village sites! Two stone crosses survive at the Hargham A11 crossroads (NHER 9159) and Whitecross Drift (NHER 9160), with another: an Ashby or Eashby Cross (NHER 31543) reported in 17th century documents. Four churches are encompassed by the parish boundary for Quidenham. The church serving the village proper is St Andrew’s (NHER 10793), a small and picturesque building mainly dating to the 13th century. Interestingly, the fact that human remains in the churchyard date to a range of periods suggests that it may have been a burial site before the erection of the church. The second church is St Mary’s in Eccles (NHER 10823) dating to around 1300 with later 14th and 15th century alterations. It has a round tower and is notable for several interesting 19th century gravestones in the churchyard. The other two churches are All Saints’ in Hargham (NHER 9187) and Wilby (NHER 10824). The tiny 14th/15th Hargham church was derelict until the 1980s, at which point local people saved it from ignominy and began the process of restoration. The interior of All Saints’ in Wilby was refurbished in 1633 after a fire, but the 14th century Decorated-style exterior is largely unaltered. Continuing in an ecclesiastical theme, Quidenham was also the location for the medieval palace of the East Anglian Bishops. All that remains at the site (NHER 10794) of this palace is a series of incomplete ditched enclosures and pond-like depression.

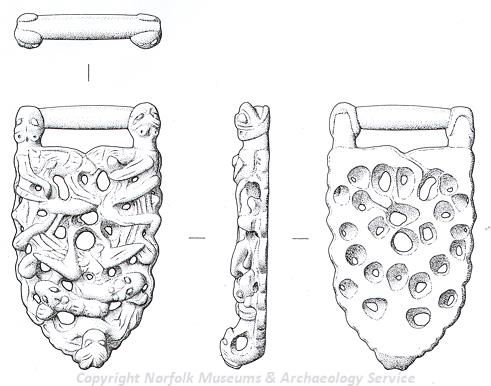

A medieval openwork and relief decorated strap-union from Quidenham. (© NCC)

As mentioned earlier, a medieval settlement centre has been identified from aerial photographs at Wilby (NHER

29582). Although the present day version of Wilby Hall (NHER

9186) is a magnificent 17th century brick hall with a rare collection of bee-holes, it is possible that the moat related to a previous medieval hall (‘Beck Hall’) that was sited here, to accompany the village. However, it is equally possible that the medieval hall lay to the north of this site as surveys of grassland here found earthworks (NHER

31185 and

31186) that could be consistent with a building of this type. The Domesday Book also recorded a medieval settlement in Hargham, and accordingly the remnants of a deserted village (NHER

11926) are identifiable through earthworks and cropmarks here. It seems that during the later stage of the medieval era the people were leaving outlying Hargham and Wilby to move to more densely populated areas, possibly including Quidenham itself.

A 15th century gilt-copper alloy figure of the Virgin Mary from Quidenham.

It is worth mentioning that a number of superb medieval finds have been found at various locations across Quidenham. Fittingly for a parish with four churches a number of these are of a religious nature. A lead Boy Bishop token converted into a pendant (NHER 29447), pilgrim badge (NHER 30382) and small figurine of an unidentified saint (NHER 39287) represent the most intriguing finds of this type. A beautiful ring brooch (NHER 30368) and seal matrix depicting a bird with foliage in its beak (NHER 24051) are amongst the other noteworthy items reported.

Several prominent post medieval buildings exist in Quidenham Parish. The foremost of these is Quidenham Hall (NHER 10820). This grand brick-built hall featuring octagonal turrets was erected in 1606 and was home to the Earls of Abermarle until 1948. At this point it became a Carmelite Monastery, inhabited by Nuns from a foundation in Rushmere in Suffolk. Originally it was a Tudor style mansion but work by the 7th Earl of Albermarle gave it the Georgian facings that are visible today. The Hall is surrounded by Quidenham Park (NHER 30517), which was in existence by 1762 and underwent alterations in 1794 and 1815 that included the widening a section of the River Whittle to form a lake. The kitchen garden and woodland relating to the Hall survive in this park. Similarly, a Hall (NHER 19788) stands within a park (NHER 30506) at Hargham. This hall was built in 1690 but was altered in 1770 and has an 18th century barn and summerhouse in its ground. The kitchen garden, now part of the park, includes many exotic plants and these set it apart from the Quidenham example. The third hall in the parish is at Eccles (NHER 10819), but this 17th century great house is no longer a private residence but is the principal building of Eccles Hall School. Although there is no associated park the remains of an icehouse (NHER 10818) used by the hall survives to the west. The last post medieval hall, at Wilby (NHER 9186), was discussed earlier so is merely noted at this point.

There is limited evidence of industrial activity in Quidenham with the site of a windmill (NHER 15051) and lime kiln (NHER 10791) noted on 18th and 19th century maps. Whilst nothing of the kiln remains, the mill dam is still clearly visible at the recorded location of the watermill. Two other site merit a brief mention: the post medieval gallows at Gallows/Gibbet Hill (NHER 9157) and the intriguing Devil’s Oven Cave (NHER 10817) which is in fact a duck decoy not a cave! Of course there are many other listed buildings from this period that interested readers may wish to visit, like those on Green Lane in the village of Quidenham (NHER 46408, 37336 and 46409).

Obviously a great quantity of post medieval artefacts have been recorded. Amongst the many coins, buckles and pottery sherds are a number of more interesting finds. A couple of children’s toys have been found; one was a small toy cannon (NHER 30370) and the other a lead figurine with Tudor dress (NHER 39287). Quite a few items of a martial nature have been discovered, such as musket balls (NHER 23223, 36198 and 45380), sword belts (NHER 30369, 31252 and 31314) and a gunflint (NHER 29648). The most intriguing find of this kind was a medal minted to commemorate the capture of the Spanish-held Fort Chagre in Panama by Admiral Vernon in 1739. This medal (NHER 30366) represents a most unusual and exciting artefact to find in rural Norfolk. Other interesting items of a more domestic nature include a thimble with stamped decoration (NHER 29447), a tobacco tamper (NHER 30370), a pastry cutter (NHER 35409) and fine finger ring with running rose decoration (NHER 29884).

After the post medieval era the majority of records refer to World War Two military structures and sites. However, there are a couple of records that date to before and after World War One. Firstly, the imposing gate-piers, gates, flanking walls and railings (NHER 46410) at the entrance to the drive of Old Buckenham Hall date to around 1911. In addition, the square, cast-iron K6 type telephone booth (NHER 46249) in Quidenham dates to around 1935, after World War One.

During World War Two the airfields at Snetterton and Eccles Road (NHER 9068) were important for sites, with the former being used by the USAAF 96th Bombardment Group until 1946 and the latter being used as a USAAF base to repair Flying Fortresses aeroplanes. Nowadays Snetterton has risen to local prominence as a motor racing track but several of the runways remain along with a hangar and water tower. The concrete platform and semi-underground building of a rare 1942-43 gun emplacement (NHER 29961) associated with the defence of Snetterton have also been noted. A Type 22 pillbox (NHER 29635) built in 1940 also survives in good condition southwest of Church Road Cottage. We end this review of Quidenham’s archaeology on a poignant note. The only other World War Two site that has not yet been mentioned is the crash site of a B17 Flying Fortress (NHER 22619) from Snetterton. This plane went down during January 1944 in frosty conditions killing all the crew, with debris from the plane marking the crash site.

Thomas Sunley (NLA), 22 January 2007.

Further Reading

Brown, P. (ed.), 1984. The Domesday Book (Chichester, Phillimore & Co)

Davison, A. and Cushion, B., 1999. 'The archaeology of the Hargham estate in Norfolk', Norfolk Archaeology 43 (2) pp257-74

Knott, S., February 2006. ‘St Andrew, Quidenham’. Available: http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/quidenham/quidenham.htm. Accessed: 22 January 2007

Mortlock, D. P. and Roberts, C. V., 1985. The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches: No.3 West and South-West Norfolk (Cambridge, Acorn Editions)

Pevsner, N. and Wilson, B., 1999. The Buildings of England, Norfolk 2: North-west and South (London, Penguin)

Rye, J., 1991. A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place Names (Dereham, The Larks Press)