This Parish Summary is an overview of the large amount of information held for the parish, and only selected examples of sites and finds in each period are given. It has been beyond the scope of the project to carry out detailed research into the historical background, documents, maps or other sources, but we hope that the Parish Summaries will encourage users to refer to the detailed records, and to consult the bibliographical sources referred to below. Feedback and any corrections are welcomed by email to heritage@norfolk.gov.uk

Walsingham is a parish in the northwest of Norfolk. Situated a few miles in from the coast at Wells next the Sea it is best known as a place of medieval and modern pilgrimage. The archaeology of the parish, however, reveals an interesting number of earlier sites and suggests there has been activity here since Palaeolithic period. The parish was formed when two smaller parishes, Great and Little Walsingham, were joined. The earliest historical records of the villages date to 1035 and both villages are mentioned in the Domesday Book. One of the most interesting manuscripts referring to the villages is the Walsingham Cartulary, a collection of charters in the British Museum, which is unfortunately undated. The first of these refers to the foundation of a shrine at Walsingham. After the foundation of this shrine the area became a place of pilgrimage. These historical documents are very useful when examining Late Saxon and medieval Walsingham and can be combined with the archaeology of the parish to understand how the villages and religious sites developed. For evidence of activity in earlier times, however, we have to turn to the archaeological evidence.

A Roman model of a goat found at the Walsingham Roman temple site. (© J. Bagnall-Smith.)

The earliest find from the parish is a Palaeolithic flint handaxe (NHER

2019). Flint tools were used throughout the prehistoric period and although their presence does not necessarily indicate occupation in an area it does mean there was human activity nearby. Several tools from the Mesolithic period have also been found. A Mesolithic blade (NHER

21106), flint tools (NHER

29923) and a flint core (NHER

39259) have been recovered from sites where there is more activity in later periods. Often evidence for activity in the Mesolithic is hard to find, as people were not living in permanent settlements but temporary camps. Comparatively, Neolithic hand axes are relatively common finds in Norfolk. Several Neolithic flint axeheads (NHER

2020 and

14934) have been found at Walsingham. A possible hoard of four axeheads (NHER

11177) was found in one location. In the Bronze Age people began to make tools out of copper alloy. Some of these tools have been found at Walsingham. A man walking his dog found a Bronze Age copper alloy knife (NHER

1955). A Late Bronze Age axehead (NHER

28254) has also been found. Some reports suggest that a hoard of Late Bronze Age copper alloy socketed axeheads (NHER

2022) was found in Walsingham chapel. They may have been moved into the building after being found elsewhere. The earliest sites recorded also date to the Bronze Age. Several possible Bronze Age barrows (NHER

2021,

2067 and

21776) have been identified. Ploughing has destroyed several of these burial mounds. All that now remains of them are cropmarks of the ring ditch that originally surrounded the mound. These ring ditches can be identified from aerial photographs. There is also evidence for activity in the Iron Age. Although no monuments have been identified several Iron Age coins (NHER

23501 and

2023) have been found. These include an Iron Age fake gold coin (NHER

29924). Many Iron Age objects have also been found on a later Roman temple site (NHER

2024). Their presence there may suggest that the temple was built on an earlier Iron Age religious site.

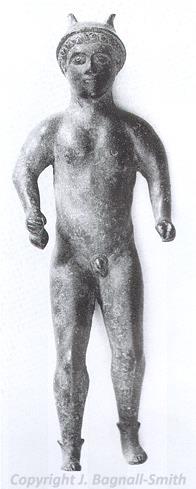

A Roman figure of the god Mercury found at the Walsingham Roman temple site. (© J. Bagnall-Smith.)

Walsingham was an important place in the Roman period. A long-term metal detecting survey has recorded thousands of Roman finds from an area north of Great Walsingham. The scatter of material spreads northwards into Wighton parish. The large number of pottery fragments, coins, brooches and building material has identified this spread as the remains of a Roman town (NHER

42850). The number of bits of exotic and high quality pottery indicate that this might have been an area of some importance. The recording of the location of finds within the town and observations of the landscape have enabled archaeologists to identify Roman roads (NHER

1922,

2041 and

2050) running through and to the settlement. Areas of buildings (NHER

21106 and

25399) and a Roman temple (NHER

2024) have been interpreted. At the temple site over 6000 coins have been recovered, many which may have been deposited there as gifts to the gods. The discovery of three figurines of Mercury, the Roman messenger god, suggests that the temple may have related to him. Other finds relating to satyrs and cupids also suggest Bacchus, the god of wine and debauchery, may have been worshipped here. Gifts of food and wine may have been left in pottery containers and ritual feasting may have taken place.

A Roman bust of a three-horned deity found at the Walsingham Roman temple site. (© J. Bagnall-Smith.)

Other Roman finds are scattered around the parish. The River Stiffkey seems to have been a concentration of activity. Coins (NHER

2026,

2028 and

2083), brooches (NHER

23336 and

23501), pieces of quern stones (NHER

16257) and fragments of pottery (NHER

2056,

12617 and

14303) are relatively common finds. At one site fragments of Roman amphorae (NHER

39259) or pottery storage vessels weighing up to 1.5kg were found! A Roman military pendant (NHER

28253) and a silver harness or belt fitting (NHER

28254) have also been recovered by a metal detectorist.

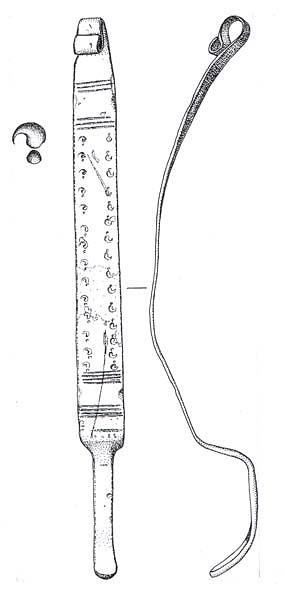

An Early Saxon girdle hanger from Great Walsingham. (© NCC)

An Early Saxon cemetery was excavated in Great Walsingham in 1658 by Sir Thomas Browne. This is the earliest recorded excavation of a Saxon cemetery in Britain. The only problem is that we do not know where the excavated cemetery was! There are two possible locations (NHER

2030 and

2024). It is possible that Sir Thomas excavated the cemetery without mentioning the Roman temple beneath it (NHER

2024). Metal detecting and fieldwalking on the other possible site (NHER

2030) found virtually no finds. This might be explained if the site was completely excavated and all traces of the cemetery removed. An Early Saxon cremation urn found in a railway cutting (NHER

2031) may be a clue to the location of the site. A set of two brooches and some rings were buried with the urn. At another site a rare brooch from Lombardy and other metal detected finds including pottery and more brooches suggest this was an area of Early Saxon settlement and burials (NHER

29923). Other exotic finds include a Merovingian gold coin (NHER

37715) that had been made into a pendant. An Early Saxon girdle hanger (NHER

28254) and buckle (NHER

28253) have also been found by metal detectorists.

The wealth of evidence for Roman settlement and Early Saxon activity contrasts rather well with the apparent dearth of archaeological evidence for the rest of the Saxon period. Excavations at St Mary’s Priory (NHER 2029) in Little Walsingham have uncovered a single Middle Saxon grave. This has been interpreted as an earlier Saxon religious centre on the same site but the evidence for this seems uncertain. The site of a possible Late Saxon church (NHER 2057) in the parish has also been identified although no evidence can be seen of this from aerial photographs of the site. An early wooden church would be hard to identify without excavation however. More circumstantial evidence has suggested that there was a Late Saxon coin mint (NHER 1121) somewhere in Walsingham. The inscription ON WALSI on two Late Saxon coins has been interpreted as meaning from Walsingham. More clear evidence of Late Saxon activity is provided by the Late Saxon box mount (NHER 28253) found by a metal detectorist in the parish. A possible Viking presence is revealed by the discovery of a Viking trefoil brooch (NHER 28253).

The development of the pilgrimage centre at Little Walsingham is well recorded in historical documents. The shrine was founded by Richeldisde Favarches in 1061 when she built the first Holy House after receiving visions. In these visions she was transported to Nazareth where she saw the house where Mary was told she was carrying the baby Jesus. She was told to build a replica of this. The first Holy House, probably a small wooden building, was built in Little Walsingham around 1061. A religious order was later founded at the site and the first prior was put in place in 1153. St Mary’s Augustinian Priory (NHER 2029) was built adjacent to the first Holy House. Later a Franciscan Friary (NHER 2036) was also built near the site. These sites became the main centre of pilgrimage in England from the 12th to the 14th century when travel to shrines further afield such as that at Compostella was more difficult. Pilgrims included Henry II, Edward I, Henry VII and the humanist Erasmus. Edward III even built a house there (NHER 13287) so he had somewhere to stay when he came to visit. The medieval priory became significantly wealthy and in the 14th century a period of expansion included the building of a chapel around the Holy House. A much larger, grander aisled church with a central tower was built to replace the Norman church in the priory. The Franciscan friary (NHER 2036) was also built at this time. To provide accommodation and facilities for the visiting pilgrims the medieval village of Little Walsingham grew around the site. This may have been a planned medieval town (NHER 43121). The archaeological evidence is not completely clear. Many of the remaining medieval buildings in Little Walsingham may have been pilgrim hostels and inns. Excavations in the 1950s underneath the modern Anglican shrine (NHER 2035) revealed foundations of a medieval inn or almonry. Other medieval structures include the Shire Hall (NHER 15129), now a museum, and a leper hospital (NHER 2060). A medieval cross stood in Common Place (NHER 2042) and the village church, St Mary’s and All Saints’ (NHER 2063) was built in the Norman period although it was significantly altered throughout the medieval period. It was seriously damaged by fire in 1961 but has since been rebuilt.

Outside of the pilgrimage centre at Little Walsingham there is plenty of other evidence for medieval activity. There are two deserted medieval settlements in the parish. Quarles (NHER 1962), possibly meaning 'circles', and Egmere (NHER 1922) have now shrunk to single farms. The earthworks of these deserted medieval villages can be seen on aerial photographs. Medieval moats (NHER 2051, 11319, and 15507) may also mark the location of medieval settlement. The Berry Hall medieval moated complex in Great Walsingham (NHER 11951) is a particular large and complex set of earthworks including moats, fishponds and rectangular enclosures around possible housing platforms. The sites of two medieval stone crosses (NHER 11952 and 14302) are also known. The site of medieval All Saints’ and St Mary’s Church, Great Walsingham (NHER 2057) can be seen very clearly as a cropmark or parchmark within a rectangular enclosure. It was demolished in 1552. All Saints’ and St Peter’s Church, Great Walsingham (NHER 2062) was built in the 14th century and this became the parish church when All Saints’ and St Mary’s was demolished.

There have been many medieval finds made by metal detecting and field walking. Unsurprisingly many of these are related to pilgrims travelling to the shrine. Several lead ampullae (NHER 14374, 23328 and 13289), or flasks for holding holy water or oils, have been found. Part of a large and ornate piece of medieval horse harness (NHER 25466) has been recovered. The gilt and enamelled decoration on the harness depicted a heraldic animal. A cross-shaped medieval reliquary (NHER 32874) with slots for holding parts of the True Cross was also found in Walsingham. A medieval boot found in a trench dug for sewers in the High Street, Little Walsingham, is a rare survival of a leather object. In normal circumstances leather would decay leaving nothing left for the archaeologists to find.

The Holy House was destroyed in the 16th century during the Reformation. The priory and friary were partly demolished and left in ruins. The Prior and Canons of St Mary’s Priory were the first in England to sign the Act of King’s Supremacy in 1534. Not all the religious men of Walsingham were happy with this decision and in 1537 Nicholas Myleham, Sub Prior, and George Gisborough were among eleven people who were tried for treason in Norwich. They were all found guilty and were condemned to death. Nicholas and George were executed at Walsingham at Martyr’s Field (NHER 2044) where possible human bones have been recovered. In June 1538 the statue of the Virgin Mary was sent to London and was burnt along with many other religious images. The property of the religious establishments was handed to the King’s Commissioner, the Holy House was destroyed and many of the buildings ransacked. Many of the late and post medieval buildings in Little Walsingham contain reused medieval stones from the religious buildings that were removed at this date. Pilgrimage to Walsingham didn’t occur again until the modern period.

Life went on however. There are records of many post medieval buildings in the parish. Abbey Farm in Little Walsingham was built on the site of the priory. This complex farmhouse may have been built in the 16th and 17th centuries. The remains of a post medieval icehouse (NHER 2059) that belonged to the farm can still be seen in the grounds of the landscaped park around the remains of St Mary’s Priory. Another house formerly in the grounds was High Grove House (NHER 15508). A police station (NHER 2060) was built on the site of the medieval leper hospital in the 17th century. Walsingham Gaol (NHER 15128) was also built at around this period. Inmates were used to turn the treadmills at the adjacent mill until they were replaced by steam power. If they escaped the rigours of the gaol some of the poorer population of post medieval Walsingham may have ended up in the workhouse (NHER 17417). Someone digging a hole for a pond in their garden uncovered the foundations of this building. Other people were not so lucky. They did not dig holes in their gardens, they just appeared! The parish appears to be riddled with post medieval chalk mines. One opened up under the Old Smithy, Great Walsingham (NHER 17900) and the back garden of a bungalow in Little Walsingham sunk into another one (NHER 42665). These mines appear to have gone out of use in the 19th century when they were partly filled up and buildings built on top of them.

A World War Two pillbox in Walsingham. (© NCC)

In the modern period the area was not untouched by the two World Wars. To the west of the parish is a World War Two airfield (NHER

1966) that was used by the Signal Corps to drop small pieces of metal over German cities. These were used to trick the German radar operators into thinking they were bombs. Around this site are a series of defences including pillboxes (NHER

12875,

16083 and

19720), spigot mortar bases (NHER

32413 and

32412), a searchlight (NHER

33742) and a Home Guard shelter (NHER

32414). Nearby was a secret auxiliary hide out (NHER

40329). This would have been used by the Resistance in the event of a German invasion and the survival of this type of monument is very rare. The village of Little Walsingham may have been defended by a machine gun emplacement (NHER

38142) built next to Aelred House.

The pilgrimage centre at Walsingham has been reinstated in the 20th century. The area is now frequently visited by followers of the Roman Catholic and Anglican faiths and interested tourists. The development of a new Anglican shrine (NHER 2035 and 34341) and a new Roman Catholic church (NHER 41650) have given archaeologists the opportunity to learn more about the archaeology of the parish. Combining this knowledge with the work of metal detectorists has enabled us to bring the past to life.

Megan Dennis (NLA), 20 January 2006.

Further Reading

Angela, M., no date. 'The Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham'. Available:

http://www.petticoated.com/walsingham.htm. Accessed: 20 January 2006.

Anonymous, no date. 'Black Lion Hotel, Little Walsingham'. Available:

http://www.blacklionwalsingham.com/. Accessed: 20 January 2006.

Anonymous, no date. 'Walsingham'. Available:

http://www.walsingham.org.uk/. Accessed: 20 January 2006.

Bond, H. A., 1960. The Walsingham Story Through 900 years (Walsingham, Greenhoe Press)

Brown, P. (ed.), 1984. Domesday Book, 33 Norfolk, Part I and Part II (Chichester, Philimore)

McColl, C., 2004. 'Roll of Honour - Little Walsingham'. Available:

http://www.roll-of-honour.com/Norfolk/LittleWalsingham.html. Accessed: 20 January 2006.

Mills, A. D., 1998. Dictionary of English Place Names (Oxford, Oxford University Press)

Rye, J., 2000. A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place-names (Dereham,The Larks Press)