Norfolk is full of wonderful churches. They are often a focus for local historical research. This guide gives you a short introduction to finding out more about churches. Many books have been written on this subject and this is a short, generalised introduction. More information can be found in the books and websites listed in the Further Reading section at the end of the text.

St Nicholas' Church, Blakeney, showing the two towers, the seven lancet east window and the clerestory. (© NCC)

Step 1 – visit the church and ask locallyIf you are interested in researching the history or archaeology of a church it is important to visit the building. Walk around the exterior and interior enjoying the atmosphere and getting to know the building. Many churches have written guides to their history and architecture. These are often available in the church itself or at the local library. Norfolk Landscape Archaeology, Norfolk Heritage Centre and the Norfolk Record Office hold copies of some of these guides. These are an important starting point. Contact the clergy or church wardens and ask locally about the history of the church. Check whether there is a local historical society (look in the Exploring Norfolk’s Archaeology pack or on the ICON database on the Norfolk Libraries and Information Service website) or ask at your local library. Libraries also often have a local history section containing copies of maps, archives and local history books. There may also be collections of old postcards and photographs that might feature the church. Search the Norfolk Online Access to Heritage (NOAH) website which contains records held by the Cultural Services department of the County Council. You may be able to find out a lot about the history of a church and also have a good idea of the research previously done.

The ruins of St Peter's Church in Stanninghall in a 19th century print.

Step 2 - Look for documentary recordsPublished information

There are many published guides to Norfolk’s churches. A full list of these can be found in the further reading section below. For a disused church Neil Batcock’s survey, The Ruined and Disused Churches of Norfolk may be of use. Several descriptions of Norfolk’s churches have been published including those by T.H. Bryant and H. Munro Cautley (see list below). You may find more information in older publications such as Blomefield’s An Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk. These may help to identify how the church has changed in the last 200 years. Although Blomefield’s “History” is now out of print it is available at Norfolk Landscape Archaeology, Norfolk Record Office and through the Norfolk Library and Information Service. These publications provide information on the history of many of the most well-known of Norfolk’s churches. If there is little information available on your chosen church you may need to examine unpublished records at the Norfolk Record Office and the Norfolk Historic Environment Record.

St Mary's Church, Bylaugh. (© NCC)

Unpublished records'Researching a Norfolk Parish Church' is a guide produced by the Norfolk Record Office. This lists how to access various unpublished sources. These include bishop’s registers, visitation records, consistory court records, faculties, consecration records and title deeds, glebe terriers, parish records, wills and churchyard surveys. These can provide information on clergy, repairs to church buildings, misappropriations of church property and goods, alteration or destruction of church buildings, the consecration of buildings and descriptions of church furniture and churchyards. For more information download the guide by clicking on the link above. In addition to church records the Record Office also hold private papers that may relate to church history. These include architectural drawings, glaziers archives and antiquarian notes. Thomas Martin’s papers may be of especial interest as these include descriptions of church buildings, furnishings and inscriptions often prior to restoration. Unpublished photographs and illustrations may occasionally be found online at Picture Norfolk or the Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service's MODES collections online system. Ladbrooke's lithographs of Norfolk churches give an idea of what the churches looked like towards the end of the 18th century. These are available at the Heritage Centre in The Forum, Norwich. Wills are an important source for the dates of various additions to churches, such as towers and porches. Bequests dated to around 1370 to 1550 have been calendered in Norfolk Archaeology, volume 38 (available at Norfolk Landscape Archaeology, Norfolk Record Office or through the Library Service). The Norfolk Historic Environment Record also holds many unpublished records for Norfolk's churches which can be consulted by appointment.

Step 3 – examine the building materials

Churches are built of a variety of materials. Although they are mainly built of locally available building materials, because they are high status buildings rich and exotic stones are occasionally used in their construction. Sometimes materials from an earlier church were incorporated into the new building. Building materials used in Norfolk churches include: local flint, clunch, carstone, ironbound conglomerate, timber framing and imported limestone. Locally made brick has been used from the medieval period. Materials salvaged from Roman sites are also used in church construction.

All Saints' Church, East Winch. (© NCC)

FlintFlint is the building material used in most churches throughout Norfolk. Early flint churches are generally built of the unprepared cobbles mortared together. Flint walls were sometimes built with the stones laid in neat courses, or in a herringbone pattern. Brick or stone details for corners or door and window dressings were introduced later. Flint was not knapped until the 14th century. Knapping involves chipping the flint to reveal the interior black surface. Squared knapping involved squaring the block of flint as well as preparing the face of the block. This was costly and consequently was used for the more expensive churches. If the flint is knapped it can then be used in decorative schemes. St Leonard’s Church, Mundford (NHER 5155) has a decorative knapped flint and brick porch. Galetting, the use of small flakes of flint or other material pushed into the mortar between the larger blocks, was introduced in the early 15th century. The small stone chips prevented wide mortar joints from being scoured by rainwater. It was used until the 19th century. Another decorative technique was the combination of flint with another material to produce flushwork. Panels of limestone were cut to shape and filled with knapped and shaped flints. These could be used to produce intricate light and dark chequerboard as well as tracery patterns, floral motifs and lettering. Fine flushwork can be seen at St Michael at Coslany in Norwich (NHER 593), at St John the Baptist's Church, Garboldisham (NHER 5570) and most impressively in the tower of St Mary's Church, Redenhall (NHER 11104). St Mary Magdalen’s Church, Mulbarton (NHER 9520) makes use of chequered flint flushwork. This technique was popular and continued to be in use, with ever more intricate designs and workmanship until the 19th century. Flint wasn’t only used in medieval and earlier churches. Christ Church, Whittington (NHER 4799), was built in flint between 1874 and 1875, as was St Alban's, New Lakenham, Norwich (NHER 49862) in the 1930s.

St Paul's Church, Thuxton. (© NCC)

ClunchClunch is rarely used in churches. It is occasionally used as a dressing over rough stones as at St Michael’s Plumstead (NHER 6691). It is more commonly used for internal masonry because it is easily carved, and sometimes for window tracery as a cheap substitute for limestone. A splendid carved clunch arch with can be seen at Wymondham library (NHER 9439) formerly the chapel of St Thomas Becket.

Carstone

Carstone is sandstone that contains high levels of iron giving it its’ distinctive red colour. The stone outcrops in the west of Norfolk and is most commonly used in churches to the west of the county. St Edmund’s Church, Downham Market (NHER 2471) is a complete carstone church dating back to the Norman period. All Saints’ Church, North Runcton (NHER 3369) was built of carstone in the 18th century. Occasionally carstone is used for architectural elements as at All Saints’ Church, Newton-by-Castle-Acre (NHER 4053) where a pair of blocked 11th century loop windows have arched carstone lintels. It wasn’t used for major buildings or those of higher status until the 19th century when it was used extensively in Hunstanton and Downham Market and surrounding villages. Carstone has also been used for decorative building like chequered designs and in the 18th century galetting.

Ironbound conglomerate

Ironbound conglomerate is a red/yellow coloured stone with many pebble inclusions. It occurs all over Norfolk except for the fens and the marshs. It is used as a building material in many churches and is commonly mistaken for carstone. At St Mary's Church, Denver (NHER 2473) carstone and ironbound conglomerate are both used.

St Faith's Church, Lenwade. (© NCC)

Imported LimestoneImported limestone is found in almost every church in Norfolk. Often imported stone was used for dressings alone as at St Stephen’s Church, Rampant Horse Street, Norwich (NHER 598). Because imported stone could be carved it was used for intricate architectural elements such as windows, doors, quoins and corners. A cheaper local material would be used for the main walls. Limestone was imported from quarries as far away as Normandy (Caen stone) and the Isle of Wight, but most came from Northamptonshire (frequently Barnack stone) and Lincolnshire. False marbles such as Sussex limestone and Purbeck limestone were often used for fonts and tombs.

Brick

Until about 1370 locally made bricks were not widely used. Brick isn’t used commonly in church architecture as a main building material until the 15th century but it was used quite extensively for internal corners, heads of doorways and relieving arches from the early 14th century at least. It was perceived as being an inferior material and was used where it would not be seen (inside towers) or where it would be hidden by plaster. St Mary's Church, Shotesham (NHER 9631) is built of brick, but faced with flint to make it look respectable. So too are parts of the very smart Holy Trinity Church, Loddon (NHER 10538).

During the second half of the 15th century brick was used sparingly to add colour to chequerwork, and to the voussoirs of windows and doorways. Brick is used unashamedly at St Mary's Church, Shelton (NHER 10188) (which has diaper patterns of darker brick) and in the tower at All Saints' Church, Wheatacre (NHER 10755). At St Leonard’s Church, Mundford (NHER 5155) a knapped flint and brick porch was added to the earlier flint building. The Norwich Road Methodist Chapel in Holt (NHER 18894) also makes good use of brick in its decorative scheme. Here a combination of red, black, blue and white bricks are used. The chapel was built in 1860. The Church of Our Lady of the Sea, Wells-next-the-Sea (NHER 39340) is a good example of an Arts and Crafts church built in 1928 in red brick.

Roman building materials

The presence of Roman building materials (brick, tile and flooring materials) within a church has often been thought to indicate the presence of an earlier church on the same site. This may not necessarily be the case. Materials may have been reused from other buildings. St Mary’s Church, Houghton-on-the-Hill (NHER 4625) contains a large number of reused Roman bricks. St Peter and St Paul’s Church, Burgh Castle (NHER 10500) contains reused Roman bricks, probably from the nearby fort (NHER 10471).

Step 4 – look at the plan and structure of the building

A typical parish church contains many of the same elements. It is important to understand the plan, or layout, and structure of the church.

Plan

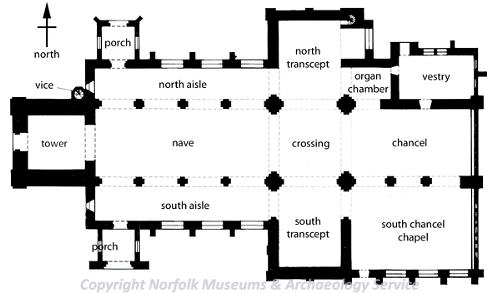

Begin by examining how the church is laid out. Make a sketch plan and label each of the areas as shown below. The plan below depicts a large, ornate and wealthy parish church. A more modest structure would consist of a simple tower, nave and chancel. By studying the plan of your church you may be able to suggest which areas may have been added later. For example the porches of many churches are added later than the original building, as at St Leonard’s Church, Mundford (NHER 5155). Aisles are sometimes added to naves to increase the width of the church as was seen most dramatically at St Nicholas’ Church, Great Yarmouth (NHER 4329) reputedly the largest parish church in England.

A plan of a typical parish church. (© NCC)

StructureStarting with the plan and identifying possible parts of the church that may have been built later you can then move on to examine the structure of the church to test your ideas. If a porch was built later than the main building then the wall of the porch should butt up against the wall of the church. It may be built of a different material or in a different architectural style to the rest of the building. By examining the structure of the building you can see how the building has grown and changed through time.

After examining the plan or horizontal, layout of the church remember also to look up. Additions can also be added vertically to the building. Towers are extended or remodelled, clerestories added and roofs replaced. You can draw a simple elevation (vertical slice) of the church and examine the structure carefully for evidence of changes to the building. The top of the tower may be a different shape to the bottom. Norfolk’s round towered churches frequently have a different shaped top that was added later. All Saints’ Church, Gresham (NHER 6617) has a set of Victorian battlements on top of its’ Saxon round tower. A roof scar, where a shallower roof was once attached to the building, shows that the roof has been replaced. Different style windows in the church indicate that they were added at different times. By using all these different clues you can begin to piece together the history of the building.

Some churches have been reduced in size, and the areas that led into aisles or chapels remain as scars. Good examples of these can be seen at St Gile's Church, Bradfield (NHER 6854) and St Mary's Church, Florden (NHER 9920). Towers have sometimes been truncated - St Peter's, Crostwick (NHER 8078) and St Paul's Church, Thuxton (NHER 8858) for example. There are also towers that were started but never finished including those at St Mary's Church, Stalham (NHER 8256) and St Paul's Church, Billingford (NHER 8858).

Round towers

Many of Norfolk's churches have a round tower. Round towers were built from uncut flints set in plenty of mortar, showing the grey, white or brown exterior of the stones. Some round towers are neatly faced with rounded flints (perhaps from the sea shore) set in even rows as at St Mary's Church, Thwaite (NHER 10477). At the other extreme some show an uneven mixture of anything hard that could be found locally even including Roman bricks at St Peter and St Paul’s Church, Burgh Castle (NHER 10500).

It seems that in Norfolk many early churches had round towers, but that the costlier square towers carried more prestige and were also much more convenient. It is very hard to fit a bell frame for more than one or two bells into a round tower. Some round towers were later rebuilt in the more fashionable square style when the parish could afford it. Often round towers only survive in small rural villages where there was never enough money to rebuild the tower.

The ruins of the church at Pudding Norton. (© NCC)

Step 5 – identify the architectural styles used in the buildingThe architectural style of Norfolk’s parish churches changed over time. Archaeologists and buildings historians have categorised these changes and defined a large number of different historical architectural styles. Often these overlap or were used in combination. However, by identifying the style of certain features in a church you can assign a rough date to parts of the building. What follows is a general introduction to the features of the main styles of church architecture. Most churches contain a mixture of different styles – windows were created, doors added and roofs replaced. When this happened the new features were generally added in the most fashionable style resulting in a hotchpotch of different architectural features. Look in the further reading section for more information on church architectural styles.

Saxon 450 to 1066

The earliest surviving churches in East Anglia date to the 10th century. These small stone structures have simple arches and windows. Many of the round towers in churches in Norfolk are Saxon. The churches themselves were often rebuilt or replaced later in the medieval period. Most round towers are older than their churches, which have sometimes been widened or completely rebuilt - as at St Mary's Church, Tasburgh (NHER 10104). A few round towers, such as All Saints' Church, Runhall (NHER 8887), and St Matthias' Church, Thorpe next Haddiscoe (NHER 10703) have been built against the west wall of an older church. The round towers of St Andrew’s Church, East Lexham (NHER 4074), St Matthias’ Church, Thorpe by Haddiscoe (NHER 10703) and St Mary’s Church, Howe (NHER 10128) are all good examples of Saxon towers. Saxon workmanship continued long after 1066 and therefore this style of architecture is also often called Saxo-Norman.

Norman 1066 to 1200

Norman architecture is very heavy and massive. The walls are thick, the round pillars are very large and all arches are semi-circular. Norman buildings were constructed by creating two stone “skins” between which rubble was poured. Columns were also rubble-filled. Walls were strengthened with flat buttresses (thicker pieces of wall) with small round-topped windows. Norman doorways are also round topped. The pillars and arches of Norman doorways are carved and set into the thickness of the wall. Some Norman doorways have multiple arches each of which is carved with a different pattern. Excellent examples of Norman doorways can be found at St Margaret’s Church, Hales (NHER 10523) and St Gregory’s Church, Heckingham (NHER 10511). Both of these churches are featured in the Norfolk Churches Trail Round Towers and Norman Doors. Norman churches were also the first to have stone ceilings – previously roofs had always been timber. Stained glass was also first used in the Norman period. St Margaret’s Church, Hales (NHER 10523), St Gregory’s Church, Heckingham (NHER 10511) and St Peter's Church, Melton Constable (NHER 3247) are excellent examples of Norman churches. Often Saxon and Norman architectural styles are termed Romanesque. The term transitional describes a style of architecture that has Norman details and pointed arches. It represents the transition between Norman and Early English architecture.

St Nicholas' Church, Salthouse. (© NCC)

Early English 1200 to 1300

The Early English style of architecture is often considered together with the later Decorated and Perpendicular styles under the name Gothic architecture. Gothic architecture can be defined by the use of the pointed arch. This enabled architects to design and build higher churches and create lancet windows. Pointed arches were often placed together in groups to form large complex windows. Early English architecture was lighter and more delicate than Norman styles. The roof no longer had to be supported on large chunky pillars but by buttresses – supports that were built outside the main walls. These walls could therefore be much thinner and contain larger windows. In the biggest and most ornate churches some buttresses were carried away from the walls themselves – leaving a space between the wall and the support. These are called flying buttresses. As buttresses supported the roof, pillars inside the church could now be much more delicate. Thin carved solid stone pillars became popular. These were carved to look like a cluster of even smaller pillars. St Mary's Church, Burgh next Aylsham (NHER 11602), St Mary's Church, West Walton (NHER 2210) and St Michael's Church, Coston (NHER 8886) are good examples of churches with mostly Early English architectural details.

St Mary's Church, Gressenhall. (© NCC)

Decorated 1300 to 1400

In the Decorated style architects began to add decorative features to the architectural styles already popular. In general Decorated architecture is more elaborate. Ribs were added to vaults and roofs and where ribs crossed carved and painted bosses were created. Windows became much more complex. Stone tracery was used to break large windows into much smaller panes. The tracery was based on ogee curves and created beautiful flowing patterns. St Mary's Church, Snettisham (NHER 1582), St Margaret's Church, Cley-next-the-Sea (NHER 6144), St Margaret's or St Mary's Church, Norton Subcourse (NHER 5282) and All Saints' Church, Wacton (NHER 10058) all contain many elements in Decorated style. The Decorated style remained popular in Norfolk and Perpendicular churches often also have strong Decorated traits.

Perpendicular 1400 to 1550s

Perpendicular architecture is very vertical. The pointed arch becomes blunted and the top of the arch became flatter forming a four-centred arch. The window is separated with vertical and horizontal stone bars (mullions) that emphasises the square look of this style. Intricate carving is another characteristic of Perpendicular pillars. SS Peter and Paul's Church, Salle (NHER 7466), St Nicholas' Church, Salthouse (NHER 6238), SS Peter and Paul's Church, Swaffham (NHER 2698) and St Martin's Church, New Buckenham (NHER 40579) are good examples of churches mostly built in Perpendicular style.

Early Gothic Revival 1550s to 1650s

After the reformation there was a move towards building churches in earlier styles. The most remarkable example in Norfolk is All Saints' Church, Westacre (NHER 3889).

English Renaissance 1600 to 1699 and Classical 1700 to 1800

English Renaissance architecture was part of a wider phenomenon of renaissance that referred back to the Classical period of Greece and Rome. This influenced all areas of thinking. Renaissance architects studied Classical buildings and based their designs on these Classical forms. At St Mary’s Church, Hillington (NHER 3515) a mural monument built in 1611 for Richard Hovel and wife, son Richard (died 1653) and wife is Renaissance in style. The church at St Andrew's Church, Gunton (NHER 6819) is built in Renaissance style. There is an early Renaissance pulpit in All Saints’ Church, Salhouse (NHER 8500) and at St Nicholas’ Church, Woodrising (NHER 8829) the large tomb of Sir Richard Southwell, who died in 1564, includes Renaissance style columns and entablature. Terracottas at All Saints' Church, Bracon Ash (NHER 9523), SS Mary and Thomas of Canterbury's Church, Wymondham (NHER 9437) and St John the Evangelist's Church, Oxborough (NHER 2642) have Renaissance styling. All Saints’ Church, North Runcton (NHER 3369) is a Classical style church built in 1713.

Gothic Revival 1780 to 1900

This period can be split into the Gothick style and true Gothic Revival. Gothick churches use Gothic-like motifs in an original way. St Margaret's Church, Thorpe Market (NHER 6765) is an example. In the 19th century there was a return to the medieval building styles. This Gothic Revival coincided with a great period of restoration and rebuilding of earlier churches. Many of the new churches built in Norfolk were in the Gothic Revival style which directly copied medieval features. These include Norwich Road Methodist Church, Holt (NHER 18894), St Mary’s Church, West Tofts (NHER 5156) and St Edmund’s Church, Hunstanton (NHER 1292). St Andrew’s Church, Brettenham (NHER 6093) and SS Peter’s and Paul’s Church, Brockdish (NHER 11106), were extensively restored and reconstructed.

20th century 1900 onward

Modern churches are often overlooked in studies of church architecture. This may be because there are as many different modern church architectural styles as there are modern churches. They make use of new materials such as concrete and reinforced glass and each is unique. Good examples include the Church of Our Lady of the Sea, Wells-Next-the-Sea (NHER 39340) built in Arts and Crafts style and St Edmund’s Church, Forncett End (NHER 10036). St Paul's Church, Tuckswood, Norwich (NHER 49863) and St Alban's, New Lakenham, Norwich (NHER 49862) are also good examples of modern churches.

There are a few churches in Norfolk that are modern rebuilds. The best known is St Nicholas’ Church, Great Yarmouth (NHER 4329). The church was gutted in 1942 by bombing and subsequent fire. The interior was rebuilt between 1957 and 1960 using the original materials gathered after the fire. St Mary and All Saints’ Church, Little Walsingham (NHER 2063) was also rebuilt after being gutted by fire in 1961. All Saints' Church, Bawdeswell (NHER 7216) is rebuilt in Classical style.

Step 6 – Look at the decoration and furnishings

Often the decoration and furnishings of a church are one of the most fascinating aspects of researching the archaeology and history of these important buildings. You might like to study the font, lectern, pulpit, rood screen, altar, piscina, sedilia, decorated bench ends and misericords. The walls of churches were often decorated. Simple and plain whitewash may hide earlier wall paintings as at St Mary’s Church, Houghton-on-the-Hill (NHER 4625). In other churches traces of these wall paintings may survive or they may have been destroyed forever by cleaning or repainting. You may also like to research the monuments in the church or the churchyard.

Step 7 – Record your findings

Norfolk Landscape Archaeology is responsible for safeguarding Norfolk’s archaeology and our aims are to record, conserve, interpret and provide information and advice on the historic environment. We would be very interested in including your research in the Norfolk Historic Environment Record so that it is freely available to future generations. Please contact Norfolk Landscape Archaeology to discuss the best way to record your hard work.

If you have enjoyed investigating your local church you may like to find out more about how people were living in your local area before it was built. You can use the Norfolk Heritage Explorer to find out more about the archaeology of your village and build a picture of how people lived in the past. You can explore the past yourself by fieldwalking, carrying out a building survey or investigating a local archaeological site. Find guidelines and advice in our other "how to..." articles.

M. Dennis (NLA), 12 April 2007.

Further Reading

Books

Batcock, N., 1991. The Ruined and Disued Churches of Norfolk (Norwich).

Blomefield, F., 1805 to 1810. An Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk (11 volumes).

Bryant, T.H., 1900 to 1915. The Churches of Norfolk (Norwich).

Farrar, E., 1887 to 1893. The Church heraldry of Norfolk (Norwich).

Fawcett, R., 1974. The Architecture and Furnishings of Norfolk Churches (Norwich).

Mansfield, H.O., 1974. Norfolk Churches: Their Foundations, Architecture and Furnishings (Lavenham).

Messent, C.J.W., 1936. The Parish Churches of Norfolk and Norwich (Norwich).

Mortlock, D.P. and Roberts, C.V., 1985. The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches (3 volumes) (Cambridge).

Mourin, K., 1999. Heraldry in Norfolk Churches (Norwich).

Munro Cautley, H., 1949. Norfolk Churches (Ipswich).

Pevsner, N. and Wilson, B., 1997. The Buildings of England. Norfolk (2 volumes) (London).

Websites

Knott, S., undated. Norfolk Churches. Available:

http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/norfolkindex.htm Accessed 12 April 2007.

Unknown, undated. Round Tower Churches. Available:

http://www.roundtowerchurches.de/Karte/karte.html Accessed 12 April 2007.

Round Tower Churches Society, undated. Round Tower Churches Society. Available:

http://www.roundtowers.org.uk/ Accessed 12 April 2007.

Stock Software Limited, 2006. The Churches of North Norfolk. Available:

http://norfolkcoast.co.uk/churches/church.htm Accessed 12 April 2007.

Fisher, P., undated. Six Parishes of the Saxonshore Benefice in North West Norfolk. Available:

http://www.saxonshorebenefice.fsnet.co.uk/ Accessed 12 April 2007.