This Parish Summary is an overview of the large amount of information held for the parish, and only selected examples of sites and finds in each period are given. It has been beyond the scope of the project to carry out detailed research into the historical background, documents, maps or other sources, but we hope that the Parish Summaries will encourage users to refer to the detailed records, and to consult the bibliographical sources referred to below. Feedback and any corrections are welcomed by email to heritage@norfolk.gov.uk

Bradenham is located in the centre of Norfolk, to the east of Necton and northwest of Shipdham. Settlement is now concentrated at Bradenham village, although the hamlets of West End and High Green are still occupied. In the medieval period the settlement pattern was much more spread out, and many moated sites and tofts have been identified. Interestingly the Domesday Book records Bradenham as being held by several people prior to 1066 including one freewoman – Aethelgyth. Baynard took control of most of the parish after the Norman Conquest. The name Bradenham also identifies a Saxon origin for the settlement – having its origins in Old English it can be translated as broad homestead or enclosure or broad river meadow. The second translation may be more likely as the River Wissey runs through the parish. The parish is particularly rich in Bronze Age finds. There is also ample evidence for medieval settlement with at least ten medieval moated sites recognised so far.

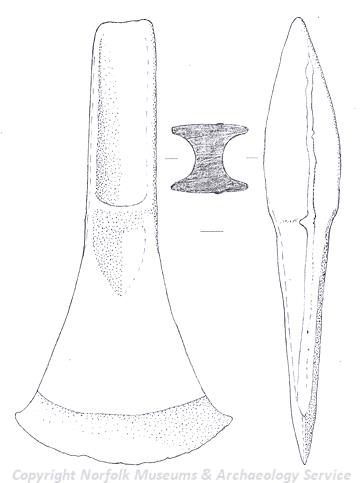

A Bronze Age palstave from Bradenham. (©NCC)

The earliest evidence for activity in the parish is at a site excavated by the NAU in 2002 during construction of a pipeline. This Neolithic to Iron Age site (NHER

37098) contained evidence for ditches and possible post hole structures. A Neolithic pick has also been recovered from the parish (NHER

2768). The richest prehistoric period is however the Bronze Age. In the same watching brief that discovered the Neolithic site a Bronze Age metal workers hoard was recovered in situ (NHER

37104) in a shallow pit. Another, possible scattered Bronze Age hoard, has been recovered by extensive metal detecting on one field (NHER

30636). Individual finds of a sword (NHER

33370), axe (NHER

8699), palstave (NHER

31495) and shaft hole implement (NHER

29492) also date to this period. This is an unusual number of finds. In contrast only one site has produced evidence for activity in the Iron Age. The random discovery of Iron Age pottery in a gravel pit (NHER

8700) during extraction suggests people were still active in the area in the later prehistoric period.

There is more evidence for Roman activity, however. A Roman road runs through the parish (NHER 8714) and metal detecting at one site has found evidence for continued occupation at one site from the Roman period through to medieval times (NHER 30636) when the settlement appears to have vanished. This occupation continued into the Early Saxon period and we have also been able to identify the location of the Early Saxon cemetery (NHER 31039) where numerous Early Saxon brooches and other personal ornaments have been recovered from graves where people were buried with rich objects. An antiquarian account also records the finding of Early Saxon pottery and spearheads within the parish (NHER 8702). The Saxon church of St Andrew’s, West Bradenham (NHER 8725) was rebuilt in the 1300s. The slightly later Norman church of St Mary’s, East Bradenham (NHER 8703) was also rebuilt in the 14th century.

In the medieval period there is extensive evidence for occupation and high status sites. Unusually at least ten moated medieval sites have been identified in the parish (NHER 1034, 1035, 1036, 1037, 2885, 8717, 8719, 8723, 8726 and 33830) and there are also several fishponds (NHER 2885 and 8720) although these may not have all existed at the same time. The majority of medieval moats surrounded manor houses and associated farm buildings, but in Bradenham it is thought that some of these moats may have surrounded more humble buildings – cottages, barns and farmyards. Moats were a fashion statement and in medieval Bradenham they were the hottest status symbol – a case of keeping up with the Joneses! The identification of a very small medieval moat or toft (NHER 33830) shows that even the lower social classes were trying to keep abreast of the latest trends.

In the post medieval period fashions changed and large, imposing houses began to be built such as West Bradenham Hall (NHER 8718) that was built in the 16th century and was the childhood home of the writer Rider Haggard. His dog Spicer is still buried in the garden. Not to be outdone East Bradenham Hall (NHER 8721) was built slightly later in the 17th century. The more grisly remains of the post medieval gibbet (NHER 8722) were excavated by Rider Haggard where he found the remains of the irons and a piece of human skull.

The parish also has remains of more modern archaeology. A bombing decoy airfield (NHER 13552) was set up here in World War Two and the remains of a pill box (NHER 17913) are recorded in the Old Vicarage garden.

Megan Dennis (NLA), 18th August 2005.

Further Reading

Allhusen, C. and P., Unknown. ‘Bradenham Hall Garden & Arboretum’. Available:

http://www.bradenhamhall.co.uk/. Accessed 27 January 2006.

Brown, P. (ed.), 1984. Domesday Book, 33 Norfolk, Part I and Part II (Chichester, Philimore)

Norfolk County Council, Unknown. ‘Norfolk Countryside’. Available:

http://www.countrysideaccess.norfolk.gov.uk/walk-07.asp?id=07. Accessed 27 January 2006.

Mills, A.D., 1998. Dictionary of English Place Names (Oxford, Oxford University Press)

Rye, J., 2000. A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place-names (Dereham,The Larks Press)

Wade-Martins, P. (ed.), 1994. An Historical Atlas of Norfolk (Hunstanton, Norfolk Museums Service/Witley Press)