This Parish Summary is an overview of the large amount of information held for the parish, and only selected examples of sites and finds in each period are given. It has been beyond the scope of the project to carry out detailed research into the historical background, documents, maps or other sources, but we hope that the Parish Summaries will encourage users to refer to the detailed records, and to consult the bibliographical sources referred to below. Feedback and any corrections are welcomed by email to heritage@norfolk.gov.uk

The small parish of Dilham is to be found in the northeast of Norfolk, immediately east of Worstead. Its name comes from the Old English for ‘a homestead where dill is grown’. The parish has a long history and was certainly well established by the time of the Norman Conquest, its population, land ownership and productive resources being extensively detailed in the Domesday Book of 1086.

The archaeological record for the parish is quite sparse until medieval times, but having said that, objects have been found from every earlier period from the Mesolithic onwards. The first evidence we have of human activity comes in the form of three Mesolithic flint axes (NHER 8187, 21250 and 32126), found at various locations in the parish. The Neolithic usually yields greater quantities of flint tools than earlier periods, but in Dilham only two polished flint axeheads (NHER 8188 and 33138) have so far been found, together with a few flakes and a scraper (NHER 30508 and 30509). Succeeding centuries have also given up little in the way of finds. The Bronze Age is represented by a single barbed and tanged flint arrowhead (NHER 30899), the Iron Age by a few pottery fragments (NHER 19542) and the same in the Roman period, plus a coin (NHER 19543) and fragments of brick and roof tile (NHER 19542). Saxon Dilham fares little better, with just a few pottery fragments (NHER 19542).

Of course this does not mean that there was little human activity in the parish in those times, merely either that artefacts may not have survived (for example wood), or that they have yet to be discovered. A comparatively small amount of metal detecting has been carried out to date, and the early archaeological record may well change in the future.

Medieval objects have been recovered in the parish, for example pottery fragments (NHER 30508 and 30509), pieces of horse harness (NHER 18517) and a jetton (NHER 19543), but it is at this time that the first structures to survive today start appearing. On the face of it, the oldest of these is St Nicholas’ Church (NHER 8210), but appearances are misleading. The original church was indeed 13th century, but the whole building was demolished and rebuilt in the early 19th century with the shell of a round west tower, which collapsed in 1899. The church was again rebuilt in 1931, reusing some old material, which gives it a style that has puzzled some. However, the medieval font survives inside. Local legend had it that there was a second church in the parish, but this was swallowed into the ground. The appearance in the 1990s of a large depression in the existing church’s graveyard may point to the origins of the legend.

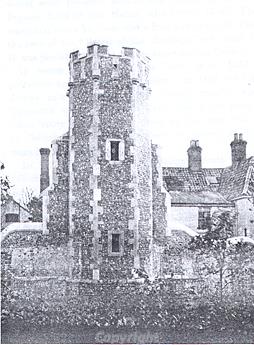

14th or 15th century tower, all that survives of Dilham Castle.

A 15th century flint, brick and stone tower with a stretch of wall, standing next to 19th century Dilham Hall, are the remains of Dilham Castle (NHER

8189), and probably represent one side of its gatehouse. The castle was probably built by Sir Henry Inglose (who died in 1450), Lord of the Manor at the time. It could more accurately be described as a fortified house, and though it was built at a time of unrest, there is no certain evidence that it ever came under attack. It also seems to have had a fairly short life, as a medieval undercroft found beneath the present hall indicates the castle was replaced with another building prior to the current hall’s construction.

Other evidence of medieval activity is less substantial, but nonetheless interesting. Man-made fishponds (NHER 42574) have been noted northwest of Dilham Hall, and it is thought Broad Fen was once a lake formed by flooded medieval peat diggings (NHER 22944), drained in the early 19th century during construction of the North Walsham and Dilham Canal (see below). Possible house platforms have also been recorded (NHER 19020 and 20221), although they may be post medieval or indeed natural features.

Dilham’s post medieval landscape must have been an attractive one. To the east of the parish were water meadows (NHER 39353), which can now only be seen as the cropmarks of drains and channels that managed the flow of water across the meadow to promote spring grass growth for livestock. There were three 19th century windmills, one (NHER 15891) to the east of the Cross Keys pub, of which the base of the brick tower remains, and one on each side of Mill Common (NHER 15892 and 15893), both of which are now gone.

Dilham and North Walsham canal showing Bacton Wood Lock.

The construction of the North Walsham and Dilham Canal (NHER

13534), completed in 1826, was to have a significant impact on the parish, and not least on the two 18th century water mills positioned on the stream that the canal replaced. Of these, one stopped working as a result, and has since vanished (NHER

15439). The other (NHER

15438) continued in use and was provided with an artificial lake (Dilham Lakes) to give it the necessary head of water that the canal had taken away. Today, only the mill’s brick wheel pit survives, and Dilham Lakes are now under pasture.

Some were quick to see commercial advantage in the canal. At about the same time as it was constructed, Dilham brickworks was built (NHER 15890), probably as part of the Dilham Hall estate, clearly seeking to use the canal for transporting its goods, and indeed sited at the head of a branch of it (‘Tyler’s Cut’). After brick making ceased, its buildings were used for a variety of trades before falling into disrepair. They have now been renovated for residential use.

Elsewhere in the north of the parish, a series of 19th century artificial waterways and islands used for boating and leisure, not on the archaeological record at the moment, were partly served by a drainage pump which is on the record (NHER 8207). Only the brick base of the pump remains. A 19th century lime kiln (NHER 16694) is marked on the 1840 Tithe map near to one of the windmills (NHER 16694), but no trace of it remains today.

Post medieval residential buildings include Manor Farm (NHER 22712), a 17th century brick and flint farmhouse with a thatched roof. The house stands near a 16th century thatched barn with slit and honeycomb windows and pigeon holes in the eaves. Dilham Grange (NHER 22711) was built in 1846 in minimalist Tudor style, and Oak Farm, formerly Tonnage Bridge Farm (NHER 24751) is an early 17th century house with later extensions,

The location of Dilham south and west of the River Ant meant the parish was an important part of the series of World War Two defensive stop lines erected in 1940 when a German incursion along the east coast was considered a possibility. The river and canal formed a natural defence line, and this was beefed up at the time by the addition of concrete pillboxes, anti tank mortar emplacements, tank traps and barbed wire. The barbed wire has long gone, and no tank traps remain, but three of the original four pillboxes have survived. These are NHER 17022, 32559 and 32564. The fourth pillbox (NHER 32563) was blown up in 1950. The concrete base of one of the anti tank mortars also survives, just south of the canal (NHER 32562).

As mentioned above, the relative scarcity of finds from the earlier periods of the parish’s existence may just indicate a lack of detailed investigation, and the picture could greatly change in future. It is hard to imagine prime land like this not being extensively utilised by man since the earliest times.

Piet Aldridge (NLA), 18 January 2006.

Further Reading

Brown, P. (ed.), 1984. The Domesday Book (Chichester, Phillimore & Co.)

Knott, S., 2005. 'Norfolk Churches'. Available:

http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/dilham/dilham.htm. Accessed 18 January 2006.

Manning, M., 1997. ‘Dilham Brickyard’, Norfolk Industrial Archaeology Society Journal.

Rye, J., 1991. A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place Names (Dereham, The Larks Press)