The Norfolk Historic Environment Record holds archives relating to many different aspects of Norfolk’s archaeology. This includes evidence for the production of clothing dating from the prehistoric period onwards. Clothes worn by people in the past rarely survive on archaeological sites. Archaeologists therefore have to look at the tools used to make clothes and the items used to hold them together to work out what people wore and how they made their clothes. This article shows how woollen cloth was made in the past. It examines the evidence from Norfolk for each part of the process and shows how raw wool from sheep and other animals was processed into fabric. This article is based on a display put together for the Woolly Wonders event held at Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse in 2006 and repeated at the Norfolk Show in 2006.

Shearing - Removing the Wool from the Sheep

First of all the wool has to be removed from the sheep. In the past this was done by hand. The sheep was firmly placed between the shearer’s legs and a pair of metal shears was used to carefully snip the wool away from the skin. This resulted in a very close shave and, if the sheep was unlucky or the shearer unskilled, a few nicks and cuts. Metal shears, possibly used to shear sheep, have been found at several sites in Norfolk including a Roman pair of shears from Snettisham (NHER 1555), a Late Saxon pair of iron shears from Sedgeford (NHER 31814) and a medieval pair of shears from King’s Lynn (NHER 1219). The technology for these objects remained unchanged until the post medieval period when man-powered pump action shears and later electric shears replaced the hand shears. Although the shearer could not cut the wool so close to the skin the sheep was less likely to be hurt during the process and shearing was much quicker and safer.

Holkham Hall, one of the most important and influential Palladian houses in England. (© NCC)

In the past sheep were important commodities. The Coke Column (NHER

39800) at Holkham Hall (NHER

1801) was erected in the mid 19th century to commemorate Thomas Coke. The capital has turnips and mangle wurzels instead of acanthus leaves and the base is decorated with reliefs including one depicting the Holkham sheep shearings. On one of the corners of the plinth is a sheep. The monument illustrates the importance of agriculture, including sheep, to the estate.

To protect his sheep from harm and to enable him to keep an eye on them a farmer would tie crotal or animal bells around their necks. These are relatively common finds (NHER 22540, 42603 and 41686). Cows, goats and other domesticated animals also wore them. If the sheep went missing the farmer would be able to find them by following the noise of the bell. If a neighbouring farmer found an unusual sheep in his flock he could tell where it belonged by the type of crotal bell it wore.

A post medieval lead alnage cloth seal from Fincham. (© NCC)

Once the fleece was removed from the sheep it could be packaged up for transportation and processing elsewhere. Lead cloth seals were widely used in Europe between the 13

th and 19

th centuries to identify where wool and cloth had come from, to regulate trade and act as a quality control check. Many of these lead cloth seals have been found in Norfolk (NHER

22755,

34966 and

40963). Cloth seals were folded around the cords securing a bundle of cloth and stamped closed. One side of the seal depicted a city’s coat of arms and the other would record the length or width of fabric or the weight of the parcel.

The cloth seal system was necessary because the fleece of different types of sheep and even different parts of a fleece from a single sheep had different qualities and colours. By selecting to use fleece from a certain part of the animal or a certain type of sheep you could radically alter the quality and texture of the resulting cloth. After selecting the quality and colour of the fleece to be used the wool then had to be cleaned and prepared for spinning.

Cleaning and Preparing the Wool

When wool is removed from a sheep it is greasy and dirty. It needs to be cleaned and prepared before it can be spun into thread. This can be done by hand, picking out lumps of dirt, twigs and pulling the fibres apart gently. It is much quicker and easier, however, to achieve the same effect by using a wool comb. This pulls all the tangles out of the wool and anything sticking in the wool can be easily removed. The earliest wool comb found in Norfolk dates to the Roman period (NHER 9786), but it is likely that they were also used before this date. Natural combs, like teasels and thistles, may also have been used.

A Roman wool comb from Venta Icenorum.

In the medieval period cards began to be used. These flat paddles had handles and a series of metal pins stuck into the face of the paddle. They were used in pairs with the wool being pulled between the teeth of the pins to separate and clean it. This was even quicker than using a single comb. A possible post medieval card has been discovered at Caistor St Edmund (NHER 37008).

After combing wool can be spun. If it is unwashed it contains lots of high lanolin (grease). Lanolin helps the fabric to repel water but is also rather smelly. Wool can be carefully washed at this stage to remove some of the lanolin. A small amount of grease makes the fibre easier to spin and so it would not have been completely removed.

Dying Wool

Wool can be dyed at a number of different stages in the process of producing cloth. If it is dyed before spinning the process is referred to as “dying in the hank”. If it is dyed after weaving it is “dyed in the piece”. In the past various natural dyes were used to brighten the colours of the fleece. People did not wear just browns, greys and whites but also produced red, blue, yellow, green, black and purple cloth. The most common dye was a plant-based red dye produced from the root of the madder plant. This has been used since the prehistoric period. Later kermes (an insect-based dye) and, from the 12th century, brazilwood were also used to produce red fabrics. Blues were made from the yellow flowered woad plant in a lengthy and complicated process. Greens and yellows could be made from the weld plant, blacks, browns and greys from tannins and purples from certain types of lichen. The Romans also created a purple dye known as Tyrian Purple, from shellfish but it was expensive and its use was restricted. To create even more variation the dyes were often mixed together.

Spinning and Plying

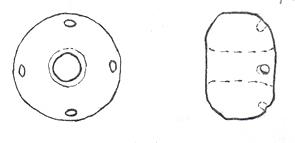

Before the invention of the spinning wheel in Europe in the 14th century all wool was spun using a drop spindle. A drop spindle is a wooden stick or rod with a weight (the whorl) on one end. Very few wooden spindles survive archaeologically. The whorl is a more common find. It can be made of pot (NHER 17652, 4626 and 5159), bone (NHER 2629 and 5439), lead, stone (NHER 9777, 3594 and 1449) or wood. Some spindle whorls are made from broken bits of pot with a hole drilled through the centre (NHER 5272).

Saxon spindle whorl found in Dickleburgh. (© NCC)

Different weight whorls would be used to produce threads of different thicknesses. To spin a thin thread a light weight would be used. To make thicker, chunkier threads a heavier weight would be employed. The spindle whorl was twisted in the working hand whilst the wool was gradually threaded onto the spindle from a stick called a distaff. These rarely survive archaeologically as, like the spindle, they were made of wood. There are illustrations from the Roman period showing how they were used.

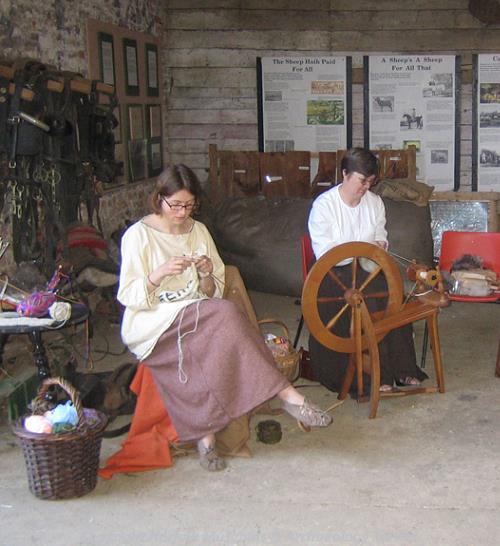

Megan Dennis (NLA) and Debby Craine, a Norfolk Heritage Explorer volunteer, during the Woolly Wonders event in Spring 2006. (© NCC)

The introduction of the spinning wheel in the 14th century was a revolution in cloth manufacture. It meant that wool could be spun from a seated position (it is most economical to spin with a spindle whorl from a standing position). The spin was placed on the fibre by the wheel rather than the hand-spun spindle. As long as the spinner could coordinate feet and hands the wheel made the job much quicker and more efficient.

Once wool is spun into a twisted thread there is nothing to stop it un-spinning itself. By plying (twisting) two threads against each other the spinner stops any untwisting. Therefore to prepare a fibre for weaving or knitting two threads need to be spun separately and then plied together. Exactly the same process is used for plying as has been described for spinning. Although first carried out on a spindle whorl it was also quicker and easier to ply using a wheel.

Weaving

The simplest type of loom for weaving cloth is a “warp-weighted” loom. This is basically a rectangular frame of wood. The warp, or vertical, threads are hung from the top of the frame and weighted with loomweights to keep them taut. Loomweights are a fairly common find (NHER 1423, 5216 and 8565). The rest of the loom often rots away because it is made of wood. Loomweights can be made of a variety of materials but are most commonly stone or pottery. If the loom is set up for a fine, thin material made using fine yarn then light loomweights are used so the threads do not snap. If coarser fabric is being woven heavier weights can be used.

Archaeologists can date loomweights by their shape. In the Bronze Age they were cylindrical, Iron Age loomweights are triangular, Roman loomweights are more pyramidal in form, Early Saxon weights are ring-shaped and Late Saxon weights bun-shaped.

Once the loom has been set up, with the warp threads hanging down vertically, the weft (horizontal) thread can be woven in and out of the threads. After each horizontal row has been completed the weft threads are pushed together with a pin beater to form the fabric. A pin beater (or weft beater) is a cigar-shaped bone tool (NHER 41335). It is usually pointed at both ends. It was used to sort out knots and tangles during weaving and to beat the weft, or horizontal, threads into place on the loom. Through repeated use a pin beater becomes shiny and polished because it absorbs the lanolin from the wool. Weaving swords and combs (NHER 11445 and 37008) were also used to push the threads into place correctly.

The warp-weighted loom was used commonly from the prehistoric period onwards. In the Roman period there is some evidence to suggest that cloth manufacture was overseen by the state in Norfolk. The Notitia Dignitatum (a late 4th century record of dignitaries and their areas of responsibility) includes a description of the controller of the state weaving-works at Venta. This might be Venta Icenorum (NHER 9786).

Before the introduction of the warp-weighted loom a simpler two-beam loom was used in the prehistoric period. This stretched the warp threads between two horizontal beams rather than using weights. In the medieval period the treadle loom, the most common horizontal loom, was developed. With later advances in technology the treadle loom was gradually mechanised and replaced with large automatic looms that required a minimum of supervision. These made the process of cloth manufacture much quicker and mass production from the post medieval period onwards has revolutionised not only fashions but also our attitudes to clothing.

Knitting and Crochet

An alternative method of production to weaving cloth was to knit, crochet or knot threads together to form a fabric. The earliest forms of knitting that survive appear to be a type of netting (also called sprang) used to create hairnets, bags and fish traps. It is very rare for these fabrics to survive, although in waterlogged conditions they are occasionally found.

Knitting and crochet were generally used for items of clothing that were difficult to make using seamed construction such as stockings, socks and hats. None of these knitted fabrics survive from Norfolk although it is fairly certain that they were used. Knitting needles and crochet hooks have been identified at others sites although none have been found in this county.

The Finished Product

Once a fabric has been woven it needs to be cut and stitched together into the finished clothes. This was carried out by hand with sewing needles. Several of these have been found in Norfolk. Needles were made from a variety of materials including bone (NHER 30165), copper alloy (NHER 22776 and 24324) and iron.

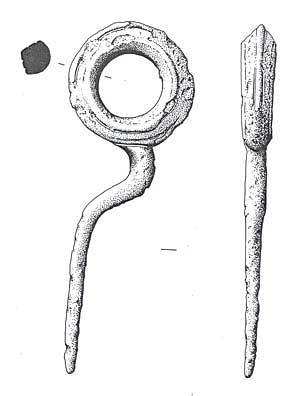

An Iron Age ring-necked pin from West Rudham.

(© NCC and S. White.)

Bone needles have been used since prehistoric times. Copper alloy needles were used for finer work, but bone needles continued to be made into the medieval period. Needles came in all different shapes and sizes – just like today. The smaller copper alloy needles used for finer work tended to get blunt. To sharpen them a bone with small grooves cut into it was used (a pinner’s bone). The needle would be run through the groove to sharpen it. Some pinner’s bones are stained green from the copper in the needles.

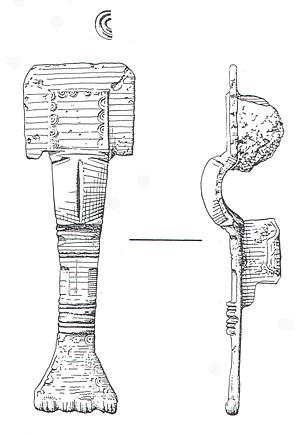

An Iron Age copper alloy toggle from North Repps. (© NCC)

Once clothes had been sewn together they could be embroidered or embellished in a variety of different ways. Feathers, gold wire, silk threads, cords, pearls and other precious stones could be attached on very luxurious clothing. Clothes could not be fastened with zips or Velcro in the past but there are plenty of toggles (NHER

25719,

31498 and

40246), buttons (NHER

6030,

14749 and

30741) and buckles (NHER

1314,

1453 and

2033) in the archaeological record that indicate how clothing was held together. Brooches (NHER

1626,

1736 and

5668), belts (NHER

13901,

14275 and

15062), pins (NHER

7850,

11440 and

14627) and clasps (NHER

21112,

24213 and

24417) would also have been used to secure items. Brooches, pins and buckles found in graves can be very useful. They give us clues as to how clothes were worn and where they were fastened. Although the clothes have rotted away from the location of a brooch archaeologists can work out what the garment might have looked like.

A complete Early Saxon small long brooch from the cremation and inhumation cemetery at Saxlingham in the parish of Field Dalling. (© NCC)

Although we don’t have any complete clothes from the past we do have very small fragments of textile. Often these are only preserved by the corrosion of metal near them. For example a hoard of Iron Age silver coins were hoarded in a pot that had been sealed with a linen or hemp cloth (NHER

25758). In some situations organic remains, like cloth, can survive. At Fishergate in Norwich (NHER

41303) the waterlogged conditions led to the survival of several pieces of medieval cloth and a complete leather shoe. The corrosion of metal objects can also help textile to survive as seen on a gilt medieval brooch from Gissing (NHER

24892) and an undated strap end from Feltwell (NHER

4927). A piece of Roman tile with a textile impression was found in Hockwold-cum-Wilton (NHER

5587). From these small remains, and the types of objects described above archaeologists can begin to piece together how clothes were made in the past.

M. Dennis (NLA), 5 January 2006.

Further Reading

Wild, J.P., 1988. Textiles in Archaeology (Princes Risborough, Shire Publications).