This Parish Summary is an overview of the large amount of information held for the parish, and only selected examples of sites and finds in each period are given. It has been beyond the scope of the project to carry out detailed research into the historical background, documents, maps or other sources, but we hope that the Parish Summaries will encourage users to refer to the detailed records, and to consult the bibliographical sources referred to below. Feedback and any corrections are welcomed by email to heritage@norfolk.gov.uk

Little Cressingham is in the Breckland district of Norfolk. The parish includes two ecclesiastical parishes – Little Cressingham and Threxton. Little Cressingham comes from Old English and may mean ‘homestead where cress is grown’. Alternatively it has been translated as ‘homestead of the family or followers of Cressa’. Land in the parish is recorded in the Domesday Book. It was held by Ralph of Tosny. The record also mentions a mill. Land in Threxton is also recorded. This village seems to have disappeared in the post medieval period except for a small farm, a few houses, a modern sewage works and the church. The appearance of both villages in the Domesday Book suggests they were settled in the Saxon period. The archaeological record reveals, however, that this area is very rich in Late Iron Age and Roman archaeology. A documentary and fieldwalking survey carried out by Alan Davison for the Ministry of Defence has revealed where settlement was located in different periods in this changing landscape.

Bell Hill Bronze Age round barrow, Little Cressingham. (© NCC)

The earliest records on the database are some Mesolithic flint flakes (NHER

4669). A possible Neolithic long barrow (NHER

22725) has been identified from old aerial photographs although the earthwork is no longer visible. Neolithic flint axeheads (NHER

4672,

4675 and

21583) have also been found. A slightly later Neolithic to Bronze Age quartzite macehead (NHER

5049) was recorded. Other Bronze Age finds include spearheads (NHER

4677), an axehead (NHER

4676) and a pin (NHER

12615). The Bronze Age barrow cemetery (NHER

5051,

5052,

5053,

5054,

5055,

5056,

5057 and

5059) at Hopton Farm is well known. At least eight barrows were clustered here. One was excavated in 1849 (NHER

5051). Inside it was a crouched inhumation. Beside the body was found a dagger and a spearhead. The skeleton wore a gold breastplate, a string of amber beads and a gold bracelet. The remains of three sheet gold boxes were also recovered. This is the only known example of a rich Wessex Culture burial in East Anglia. A second barrow (NHER

5053) was excavated in the 1970s. Unfortunately ploughing had destroyed the burial but two ditches surrounded the barrow were recorded. Although some of the remaining barrows can be seen as earthworks others have now been flattened by ploughing.

The area is rich in Iron Age finds. These include coins (NHER 4678) and a pin (NHER 29078). The fieldwalking survey has identified an area of probable Early Iron Age settlement (NHER 24681). A second, later, settlement (NHER 24672 and 24687) has also been recorded. Part of an Iron Age spindle whorl has been recovered from this site. Woodcock Hall Iron Age to Roman settlement (NHER 4697) has been known since the 19th century. Systematic fieldwalking and metal detecting have recovered an enormous number of Iron Age and Roman finds including coins, pottery, building materials and metal objects. This was an area of significant settlement from the Late Iron Age until the 4th century AD. To the south of the stream the number of mid 1st century military finds recovered from a small plateau suggests this is the site of a Claudian fort built to guard the river crossing.

Cartoon depicting the discovery of Saham Toney 2nd century AD fort. © Eastern Daily Press.

The very hot summer in 1996 enabled the identification of cropmarks of a second later fort straddling the Peddar's Way (NHER 1289, a Roman road) where it crosses the stream at the Woodcock Hall site (NHER

4697). Traces of roads and structures within the large fort can also be seen on aerial photographs. A separate horse compound has been identified. The fort was the garrison for around 800 Roman legionaries and cavalry and was probably built in the second half of the first century AD on the site of an earlier Iron Age site and close to the earlier Claudian fort. It may have been constructed in response to the Boudican revolt. Another possible Roman road (NHER

5072) also passes through the parish. A scatter of Roman material has been interpreted as a linear settlement (NHER

24698 and

24699). This probably runs either side of a Roman road. A Roman building (NHER

12262) has also been recorded. Roman pottery fragments (NHER

4679,

24675 and

24677) are a very common find. They were recovered from practically every field surveyed during the fieldwalking. Whilst coins (NHER

35101,

35288 and

35289) are less common they are still fairly widespread especially in areas that have been metal detected. Other interesting Roman finds include a carnelian intaglio of Minerva (NHER

5059), a copper alloy duck figurine (NHER

35101) and some late Roman military objects (NHER

35288).

Fieldwalking has also identified a possible Early Saxon settlement (NHER 24703) and a cemetery (NHER 35101) where several Early Saxon brooches and other personal ornaments have been recovered. These include a disc brooch with an unusual openwork design (NHER 35101). Another Early Saxon brooch (NHER 35288) was found by a metal detectorist. It is rumoured that All Saints’ Church, Threxton (NHER 4686) has Saxon foundations although there is nothing showing above the ground to corroborate this. A series of Late Saxon to medieval pits (NHER 36308) have been excavated however. These were on the site of the former village hall. They were probably cesspits at the back of a row of small houses or tenements. Exciting Late Saxon finds include brooches (NHER 4685, 4707 and 12770), a bridle link (NHER 35289) and a lead plaque (NHER 35101). This plaque may be a model for a strap end. This would be pressed into a clay mould so that a copper alloy copy of the lead model could be produced. A Late Saxon or medieval bone skate was also discovered.

All Saints' Church, Threxton. (© NCC)

All Saints’ Church, Threxton (NHER

4686) has a Norman tower. The rest of the structure was built 1300. It was heavily restored in 1866. St Andrew’s, Little Cressingham (NHER

4722) is partly ruined. The building contains Norman fragments although it is mostly in Decorated style. It was repaired and restored in the 18th and 19th century. Several areas of medieval settlement have been identified after fieldwalking. These include areas of occupation (NHER

4706,

24679,

24703 and

24706) around Little Cressingham High and Low Common. Low Common Farm (NHER

24679) has recently been demolished although the scatter of material around it suggests there was occupation here in the medieval period. A possible short-term settlement (NHER

24673) is located in the centre of one of the commons. This may only have been occupied for a short time before being returned to common land. Two named areas of medieval settlement have been identified. Hopton Manor (NHER

18339) was located around Hopton Farm. The deserted medieval village of Threxton (NHER

4707) is well known and the church and Church Farm are all that now remains at the centre of the village. There were twenty three taxpayers living there in 1377. By 1635 there were only four open fields and in 1805 one house. Slight earthworks of the village can still be seen. Possible medieval buildings (NHER

36308) have been excavated on the site of the former village hall. Earthworks of medieval ridge and furrow (NHER

31782) can also be seen on aerial photographs. Medieval pot is found widely on most fields within the parish. A seal ring bearing a cross of Lorraine (NHER

4690) is a rather more unusual find.

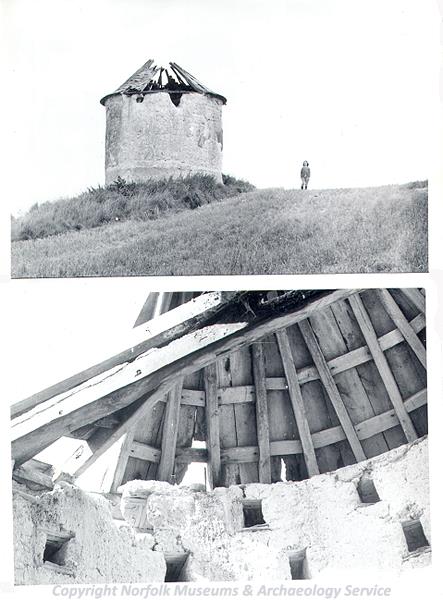

The exterior and interior of a post medieval dovecote at Threxton. (© NCC)

Thomas Barton did antiquarian research within the area in the post medieval period. He amassed a large collection of local objects, most probably from the Woodcock Hall site (NHER

4697), and placed them in a museum in his home Threxton House (NHER

5070). The other large house in the parish is called Clermont (NHER

5071). Clermont or ‘The Hall’, as it is known locally, was built in 1812 by William Pilkington. It was originally a hunting lodge for Lord Clermont. This grand plastered brick Italian style building even had its own pumphouse (NHER

44324) to pump water up to the gardens. There is also a post medieval dove cote (NHER

4692) and icehouse (NHER

5069). Little Cressingham is famous for its very unusual post medieval water and windmill (NHER

4714). This is one of only two such examples in Norfolk and has been lovingly restored by the Norfolk Windmill Trust. The mill had three sets of stones – one on the first floor driven by a waterwheel and two on the fourth floor driven by sails. The sites of two other windmills are known. The smock mill (NHER

15246) was demolished in 1821 when the water and windmill was constructed. Another windmill (NHER

31122) is marked on an 18th century map. The site of a saw mill (NHER

11833) has now been destroyed by a plantation of trees.

Megan Dennis (NLA), 5 May 2006.

Further Reading

BBC, 2003. ‘BBC – Norfolk Restoration – Little Cressingham Mill’. Available:

http://www.norfolkmills.co.uk/Windmills/lt-cressingham-smockmill.html. Accessed: 5 May 2006.

Brown, P. (ed.), 1984. Domesday Book, 33 Norfolk, Part I and Part II (Chichester, Philimore)

Brown, R.A., 1986. ‘The Iron Age and Romano-British Settlement at Woodcock Hall, Saham Toney, Norfolk’, Britannia XVII, 1-58

Davison, A.,1994. ‘The Field Archaeology of Bodney and the Stanta Extension’, Norfolk Archaeology XLII Part 1, 57-79

Neville, J., 2003. ‘Norfolk Mills – Little Cressingham water windmill’. Available:

http://www.norfolkmills.co.uk/Watermills/lt-cressingham.html. Accessed: 5 May 2006.

Neville, J., 2004. ‘Norfolk Mills – Little Cressingham smock windmill’. Available:

http://www.norfolkmills.co.uk/Windmills/lt-cressingham-smockmill.html. Accessed: 5 May 2006.

Mills, A. D., 1998. Dictionary of English Place Names (Oxford, Oxford University Press)

Rye, J., 2000. A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place-names (Dereham, The Larks Press)

Wayland Partnership, unknown. ‘Wayland Site – Lt Cressingham & Threxton Homepage’. Available:

http://www.wayland.org.uk/site/site/Lt%20Cressingham%20&%20Threxton. Accessed: 5 May 2006.