Introduction

Tracing the history of a house can be a fascinating experience, but it can also be a frustrating one. Sometimes there will be many records surviving for the building you are studying, sometimes none at all, and the likelihood of finding relevant material decreases the further back you go in time. You may also be surprised at how time-consuming the research can be. This guide provides advice on how to get started and lists resources which you may find useful.

Chaucer House is a 15th or 16th century timber framed and jettied house in Bawdeswell. (© NCC)

Step 1 Ask around locallyYou may be surprised by how much you can learn locally. Ask your neighbours if they know anything about the house. Check whether there is a local historical society (look in the Exploring Norfolk’s Archaeology pack) or ask at your local library. Libraries also often have a local history section containing copies of maps, archives and local history books. There may also be collections of old postcards and photographs that might feature your house.

Step 2 Identify the materials used in the building

You can find out a lot about the history of a house just by looking at it. It takes professionals years to develop expertise but you can start with the basics and begin by looking at the types of materials used to get an idea of the date of your house. You can find out more about general building materials on the Looking at Buildings website. Before the Industrial Revolution most houses were built with local materials. The most common building materials in Norfolk are flint, carstone, clunch, brick, timber and clay lump. Plaintiles, pantiles and thatch are used on roofs.

Flint

Flint is the most common local building material in Norfolk. It is used throughout the county. Early flint buildings are generally built of the unprepared cobbles mortared together. Later brick or stone details for corners or door and window dressings are introduced. Flint was not knapped until the 14th century. Knapping involves the chipping of the flint to reveal the interior black surface. An early example of a knapped flint building is the chapel of St James Hospital in Horning (NHER 8444). Squared knapping involved the squaring of the block of flint as well as the preparation of the face of the block. This was costly and consequently was generally used for churches and high status buildings such as the Benedictine Priory, Great Yarmouth (NHER 4295). Galeting, the use of small flakes of flint or other material pushed into the mortar between the larger blocks, was introduced in the early 15th century and is used to good effect in the Norwich Guildhall (NHER 657). It was common until the 19th century. Another decorative technique was the combination of flint with another material to produce flushwork. Panels of stone were cut to shape and then spaces between these stones were filled with knapped and squared flints. These could be used to produce intricate light and dark chequerboard and other designs. The earliest example of flushwork is probably the Friary gatehouse at Burnham Norton (NHER 1738) which dates to 1320. This technique was popular and continued to be in use, with ever more intricate designs and workmanship until the 19th century.

Foulsham House. (© NCC)

CarstoneCarstone was used widely in the Saxon period and can be seen in many Saxon churches in Norfolk. More recently it has only been used in the northwest of Norfolk where it is locally available. In the 17th century it was combined with brick. In the 18th century it was used in more minor buildings such as stables and outbuildings. In the 19th century it was built into almshouses, estate cottages, lodges and schools. It wasn’t used for major buildings or those of higher status until the 19th century when it was used extensively in Hunstanton (NHER 44245, 42737 and 1292) and Downham Market (NHER 12227, 122222 and 2471) and surrounding villages. Carstone has also been used for decorative building techniques like chequered designs and in the 18th century galetting.

Clunch

Clunch is used in a similar area to carstone and was dressed and treated like stone, although it is considerably less durable.

Brick

Until 1370 locally made bricks were not widely used. Once brick had become accepted for major buildings in the 15th century its use filtered down to smaller more modest houses although it was usually used for embellishment rather than the main building material in these smaller properties. Often a timber framed building was sandwiched between two brick gables, or brick gables were added to older houses. Sometimes bricks were used for the front of the house (the part which made an impression) but cheaper local building materials or rubble were used for the rear of the building. It wasn’t until the 16th century that smaller houses were constructed entirely of brick. Until the advent of the railways bricks were made locally and from the 17th century permanent kilns were built near to major towns. There are some local brickworks in Norfolk that can be identified by the colour, shape and size of the bricks. These include the Heacham Brickworks (NHER 1422) that were famous for the deep rich red colour of the bricks and also for the production of decorative moulded plaques. The Gunton brickworks at Costessey were also famous for their moulded and decorative brick tiles known as Cosseyware. Bricks have been used consistently since the 16th century and gradually replaced timber. The way the bricks were placed developed over time and can be a good indicator of the date of a house. To see an explanation of the different types of brickwork used at different times go to the Hidden House History website. An in-depth history of bricks has been published on the Looking at Buildings website.

Timber

Timber was a popular building material from the medieval period to the end of the 17th century. In Norfolk timber was most popular in the south where there were still considerable supplies of wood. In other areas timber was much more expensive. This meant that old timber frames were reused and recycled. External cladding on timber-framed buildings were generally wattle and daub panels. These were often replaced with clay lump in the 19th century as they wore out. In the 18th century many ‘old-fashioned’ timber framed buildings were modernised and clad in brick or plaster made to look like brick. Good examples of this can be seen in New Buckenham (NHER 40617, 40621 and 40630). From the front the buildings appear to date to the 18th century but the brick and plaster fronts hide much earlier medieval timber frames. By the Victorian period, however, timber frame was back in fashion and many houses were built with mock timber frames.

Clay Lump

This was used in the south of Norfolk. Clay was combined with horsehair or straw and moulded into blocks and air dried. Blocks were cemented together with a type of clay slip. Clay buildings must have a solid flint or brick foundation and need to be protected from the weather by a layer of limewash or tar. This method of construction did not become common until the 17th century. Clay lump was mostly used in low status dwellings – cottages and outbuildings.

Plaintiles

These clay tiles are as old as brick and were fired in the same kilns. They were first used in high status houses before more modest dwellings.

Pantiles

These are Dutch in origin and are S-shaped clay tiles. They were first imported into Norfolk in the 17th century. English production didn’t begin until 1710 and the earliest use in Norfolk dates to around 1740. From the mid 18th century onwards pantiles were glazed, in Norfolk almost always black. Pantiles gradually replaced thatch from the middle of the 18th century.

St Margaret's, Hockham is a medieval timber-framed hall house. (© NCC)

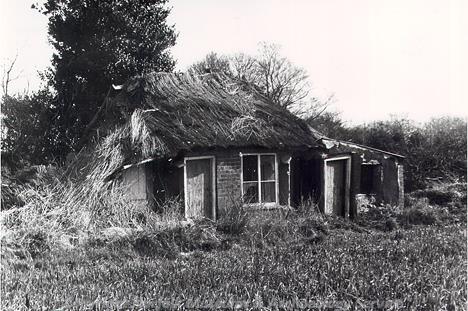

ThatchThatch is continually replaced. This makes it incredibly difficult to date but documentary references show that the use of thatch was common even before 1066. Norfolk reed is the best thatching material although it is expensive to cut and transport. Straw was cheaper and lighter and was more commonly used on smaller houses. Norfolk reed was used extensively by the architects of the Arts and Crafts movement in the early 20th century. More information on different types of thatch and the materials used for thatching can be found on the Looking at Buildings website.

The School House, Hardingham, built in Gothick Revival style. (© NCC)

Step 3 Look at the style of the buildingAfter considering what your house is made of the next step is to look at how it was constructed and the style of the building. You can look at the various different component parts of the house - windows, doors, the facade (front) and other features. These can all provide clues as to the age of the building.

Windows

The style of windows changes through time. They can be a good clue to the date of your house but remember that they have often been replaced with more modern styles and occasionally old windows can be put into a more modern house to mimic an earlier style. To see an explanation of the different styles of window used at different times go to the Hidden House History website.

Doors

The style of doors and doorcases or frames are also important to consider, although like windows they can be easily replaced. Remember to look at the external and internal doors and door furniture such as boot scrapers, door knockers, bell pulls and letter boxes. You can find out more about the styles of different doors on the Hidden House History website.

Façade

The way a house looks – the design of its façade or front has altered over time. The facade reflects current fashions and the way the house has been constructed. The facade can be covered with a more expensive material or decorated with terracotta, bricks or marble. A facade will also alter over time. In the Georgian period many houses in Norfolk were faced in red brick to hide their timber framing. Several good examples can be seen in New Buckenham (NHER 40617, 40621 and 40630). You can find out more about how building facades changed over time on the Hidden House History website.

Features

Small architectural details can reveal a lot about the date of construction of a house. By identifying original doorknobs, chimneys, weather vanes, railings, brackets and tiles you can find clues about the age of your building. Look at the Hidden House History website for more examples of dated features.

Binham from the air. (© NCC)

Step 4 Look at maps and aerial photographsYou may be able to roughly date when your house was built by looking at old maps. You may also be able to identify changes in the boundaries and size and shape of the building. Some maps also include the names of owners and occupiers. There are a variety of different maps available for consultation:

Ordnance Survey maps (1830 onwards)

The earliest Ordnance Survey maps date back to the 1830s. The first edition 6 inch Ordnance Survey maps (surveyed between 1879 and 1886) are available online on E-Map Explorer. Other Ordnance Survey maps are available at Norfolk Landscape Archaeology and the Norfolk Heritage Centre or can be ordered directly from Ordnance Survey.

Tithe maps and apportionments (around 1836 to 1850)

Tithe maps usually cover a whole parish and show individual buildings and field boundaries. The apportionment that accompanies the map lists the names of the owners and occupiers of each property. Tithe maps are available online on E-Map Explorer. Digital tithe maps can be consulted at Norfolk Landscape Archaeology. Most are also available on microfilm at the Norfolk Record Office.

Inclosure maps and awards (around 1750 to 1850)

These large scale plans give details of land ownership, highways, footpaths and boundaries. They do not exist for all parishes and may not cover a whole parish. Some Inclosure maps are available online on E-Map Explorer. They are also available at the Norfolk Record Office.

Private estate maps (from the 16th century onwards)

Private estate maps only survive for some parishes. They cover land owned by one large estate only but occasionally mention adjacent land owners. They are available at the Norfolk Record Office.

Road order maps (1773 onwards) and deposited plans (1809-1952)

Road orders were made to close or divert roads and footpaths. Deposited plans show land affected by Parliamentary Bills concerning railways, canals and turnpike roads. They include the names of owners and sometimes of land affected by the proposed schemes. They are available at the Norfolk Record Office.

Aerial photographs

You may be able to roughly date your house by looking at aerial photographs. You may also be able to identify changes in the boundaries and size and shape of the building. The Norfolk Aerial Photographs Collection housed by Norfolk Landscape Archaeology contains over 80,000 photographs dating from the late 19th century to the present day and can be consulted by appointment. Aerial photographs taken in 1946 and in 1988 are available online on E-Map Explorer.

Moat Farm, a 14th or 15th century timber framed hall house in Bedingham. This photo shows the queenpost roof. (© NCC)

Step 5 Find documentary sourcesDocumentary sources may help you to trace the history of the building's structure. They can give information on previous uses of the building. You can also find out about who lived in your house in the past. The best place to start a documentary search is the internet. The Norfolk Record Office has an online catalogue and there are several other websites highlighted here that can help you to trace the history of your house. To obtain as complete a picture as possible you will have to look at a variety of different sources.

Published information

If your house is of special historic or architectural interest it may be ‘listed’ by English Heritage. The descriptions of listed buildings can be consulted online on the Norfolk Heritage Explorer. In addition to the information available on the website Norfolk Landscape Archaeology hold photographs, plans, survey reports and aerial photographs of buildings which can be consulted by appointment. Pevsner’s Buildings of England and the Victoria County History should be available in your local library or can be consulted at Norfolk Landscape Archaeology. Local directories are published lists of residents and tradesmen for each town or village. They can be used to trace the occupants of a house. In Norfolk they were published intermittently during the 19th century, although the earliest for Norwich dates to 1783. They include White’s, Kelly’s and Jarrold’s Directories. They are not complete. They are available at the Norfolk Record Office and some have been digitised and can be searched on the Historical Directories website.

Unpublished information

Unpublished documents such as title deeds, sale particulars, census records, electoral registers, taxation and rating records, manorial records, wills, probate records and manorial records can all be helpful when trying to identify when your house was built and more specifically who lived there and when. Most of these records are kept at the Norfolk Record Office or The National Archives at Kew. The Norfolk Record Office has compiled a useful guide to using unpublished records to research your home called Tracing the History of your House.

Certain records are available online. The system of compulsory land registration now operating in England and Wales developed gradually during the 19th and 20th centuries. In some counties, registration did not become compulsory until the 1950s. The land register includes details on the location and extent of the property, current owners and details of mortgages and rights of way. The land register can be consulted by members of the public and information downloaded online from the Land Registry.

You can search the 1901 census and the 1841 to 1891 censuses online. Searches are free although a charge is made to download images and see an image of the actual census page. The location of surviving manorial documents from Norfolk are recorded in the Manorial Documents Register.

Unpublished information can also include building plans and architectural drawings. Since the late 19th century, new buildings and developments have required approval by the local authority. Norfolk Landscape Archaeology and the local Planning Departments of the district councils may hold planning applications and architectural drawings. Some older planning applications are held by the Norfolk Record Office. Norfolk Landscape Archaeology, Norfolk Heritage Centre and the Norfolk Record Office also have collections of photographs of local buildings. Some are available online on the Picture Norfolk database.

A 19th century house in Catfield constructed of puddled clay and straw with a skin of bricks added in the 19th century. This type of construction is typical of vernacular architecture in the Broads. (© NCC)

Step 6 Record your findingsNorfolk Landscape Archaeology is responsible for safeguarding Norfolk’s archaeology and our aims are to record, conserve, interpret and provide information and advice on the historic environment. We would be very interested in including your research in the Norfolk Historic Environment Record so that it is freely available to future generations. Please contact Norfolk Landscape Archaeology to discuss the best way to record your work.

If you have enjoyed researching the history of your house you may like to find out more about how people were living in your local area before your house was built. You can use the Norfolk Heritage Explorer to find out more about the archaeology of your village and build a picture of how people lived in the past. You can explore the past yourself by fieldwalking, carrying out a building survey or investigating a local archaeological site. Find guidelines and advice in our other "how to..." articles.

M. Dennis (NLA), 23 January 2007.

Further Reading

Books

Barratt, N., 2001. Tracing the History of Your House (London, Public Record Office).

Clifton Taylor, T., 1987. The Pattern of English Building (London, Faber and Faber).

Cunnington, P., 1999. How Old is Your House? 3rd revised edition (London, Alphabet and Image Ltd).

Brunskill, R.W., 2000. Illustrated Handbook of Vernacular Architecture. 4th revised edition (London, Faber and Faber).

Powell, C., 1984. Discovering Cottage Architecture (Princes Risborough, Shire Publications).

Websites

House Detective, 2003-2006. The Online House Detective. Available:

http://www.house-detectives.co.uk/ Accessed 12 April 2007.

Padimax Limited. 2002-2206. My Old House - Every house has a story to tell what's yours? Available:

http://www.myoldhouse.co.uk/ Accessed 12th April 2007.

The National Archives, undated. Starting house history research. Available:

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/househistory/guide/ Accessed 12 April 2007.

The Building Books Trust, 2004-2006. Looking at Buildings. Available:

http://www.lookingatbuildings.org.uk/ Accessed 12 April 2007.

BBC, undated. Architectural Styles Across Britain. Available:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/gallery_buildingstyles_01.shtml Accessed 12 April 2007.

Tinniswood, A., 2001. A History of British Architecture. Available:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/architecture_01.shtml Accessed 12 April 2007.

The History Channel, 2004. Hidden House History. Available:

http://www.hiddenhousehistory.co.uk/?gclid=CNLp193s8IcCFQ5eEQodL3gRgg Accessed 12 April 2007.

Geffrye Museum, undated. Geffrye Museum. Available:

http://www.geffrye-museum.org.uk/ Accessed 12 April 2007.

Ross, D. and Britain Express, 2003. English Architecture - a history. Available:

http://www.britainexpress.com/architecture/index.htm Accessed 12 April 2007.

The NAtional Archives, 2002-2007. Access to Archives. Available:

www.a2a.org.uk Accessed 12 April 2007.

The Generations Network Inc., 2007. Ancestry.co.uk. Available:

www.Ancestry.co.uk Accessed 12 April 2007.

Tyrell-Lewis Associates Limited, 2001-2007. Bricks & Brass - the period house website. Available:

http://www.bricksandbrass.co.uk/ Accessed 12 April 2007.