This Parish Summary is an overview of the large amount of information held for the parish, and only selected examples of sites and finds in each period are given. It has been beyond the scope of the project to carry out detailed research into the historical background, documents, maps or other sources, but we hope that the Parish Summaries will encourage users to refer to the detailed records, and to consult the bibliographical sources referred to below. Feedback and any corrections are welcomed by email to heritage@norfolk.gov.uk

The bustling parish of Poringland is situated in the south of Norfolk. It lies to the south of Bixley and to the north of Howe. The origins of its name are uncertain, it should mean ‘land of the people of Porr’ but no such name is known. Porr means leek in old English, so perhaps the parish has some connection with the growing of this vegetable. Nevertheless the parish has a long history and was certainly well established by the time of the Norman Conquest, its population, land ownership and productive resources being extensively detailed in the Domesday Book of 1086. This source mentions extensive agricultural smallholdings and, more importantly, the presence of a church in this period.

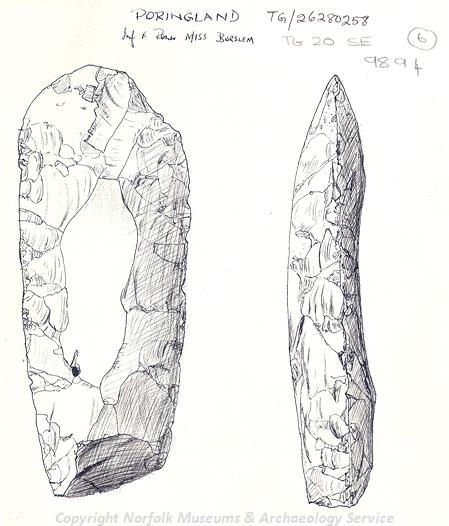

Part of a Neolithic flint axehead found in Poringland. (© NCC)

The earliest archaeological evidence for human activity in the parish dates to the Neolithic period. This takes the form of flint implements (NHER

9893), in particular chipped or polished axes (NHER

9892,

9894 and

14843). However, the scattered distribution of these finds does not suggest any significant occupation. A single scatter of prehistoric potboilers (NHER

9899) has been found, but these are very common across Norfolk and not indicative of human settlement in this low a concentration.

As we move into the Bronze Age activity seems similarly limited. Work at the gravel pits recovered pieces of pottery (NHER 9895) from this period. It was also claimed that urns and human remains were also recorded but subsequently lost. This is somewhat frustrating as these finds may have indicated the presence of burials or a barrow here, which would have been a significant find for the parish. Aerial photography has identified old field boundaries and a ring ditch (NHER 15770) which may be from the Bronze Age, but this is the sum total of information relating to the Bronze Age. Pottery sherds (NHER 13559) found to the southeast of the village centre are the only Iron Age finds that have been recovered up to now.

Metal detecting has recovered a number of splendid Roman objects. The most significant and glamorous of these was a gold ring inset with a coin of the emperor Postumus (NHER 34477). This artefact is an incredibly rare example of such jewellery, and is one of only two ever found in Britain. Unsurprisingly the British Museum purchased the piece, allowing a little piece of Poringland’s past to be viewed by a large audience. A gold thumb ring (NHER 9896), found in 1818 on a ploughed surface, constitutes the other glamorous Roman find. More mundane finds made include Roman greyware pottery sherds and a military buckle (NHER 13559) and a coin of Constantine (NHER 30241). A dense grouping of sherds of very similar form (NHER 34698) may also suggest a kiln due east of Blackford Hall, at the boundary between Stoke Holy Cross and Poringland, was operating at this time.

The presence of Saxon inhabitants in the parish is attested to by the discovery of twelve Christian burials (NHER 9902) in a probable churchyard dating to the latter part of the period. More burials have been postulated on the Heath. Here, five iron spearheads showing fire damage were retrieved from a mound (NHER 9898) and surely show some sort of ritual or burial deposit made early on in Saxon times. Sadly artefacts are thin on the ground with only a fragmented disc brooch and pieces of pottery surviving (NHER 13559). Hopefully further work in the parish can improve the understanding of this part of the Poringland’s history as the current evidence certainly provides a reason for such curiosity.

All Saints' Church, Poringland. (© NCC)

The majority of medieval evidence in Poringland comes from buildings. A little known fact is that in medieval times there were two churches here: St Michael’s and All Saints’. The site of St Michael’s (NHER

9905) is in West Poringland, with the church being demolished in 1540. The reason for this action is unknown but it was so completely removed that many local people were unaware of its existence. Interestingly the nearby 16th century farmhouse at Westgreen Farm (NHER

25736) has structural elements that date to the medieval period so it is possible either this building had some links to the church or that stone from the ruins was incorporated into it at a later date. The church that remains, All Saints’ (NHER

4703), dates mostly to the 14th to 15th century but has a Norman tower (possibly part of the church mentioned in Domesday). It forms the impressive centre point of the modern village with the grotesque figures peering round the gables at roof level proving particularly eye-catching. Those entering the church may want to take in the beautifully carved font with its depiction of a large flower, shield-bearing angels and animals representing the four authors of the Gospels. Two of the cottages situated in Rectory Lane (NHER

4702), Middle Cottage and No. 3, also relate to the medieval period as they were once combined as part of a hall house. That the medieval period may have been a quiet time for the parish may be suggested by the lack of objects recovered. Apart from a nice example of an Edward I penny (NHER

25315), minted at Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk, little of significance was found.

Church Farmhouse, Poringland. (© NCC)

Poringland’s post medieval landscape would have been dominated by the imposing Poringland Heath windmill (NHER

4762). This towering structure was reputed to be the highest standing windmill in the country but fame did not prevent its replacement with a tower mill in 1825, and even this does not survive to the modern day with its demolition occurring in 1906. Other industrial remains on record include a brick kiln (NHER

4763) noted on an 1830 map and a flint and cement tank (NHER

4699), which may have been a component of a tannery. Its association with the fine 16th century Church Farmhouse (NHER

4700) on the periphery of the village may have suited this function as tanning was an unpleasant and smelly process.

A number of post medieval residential buildings survive in Poringland. Of particular interest is the brick and flint built Porch Farm (NHER 4701), dating to the 16th century. Whilst undergoing restoration it was found to have a hidden room although whether this related to its possible function as a priest’s house, as suggested by a documentary source of 1900, is unclear. A somewhat more recent structure is the K6 telephone kiosk (NHER 45852) south of All Saints’ Church, of a design produced in 1935 by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. Metal detecting has retrieved a small number of objects and a large coin hoard (NHER 9900), comprising of forty-six silver coins and one bronze coin – which was dated to 1851. Possibly more artefacts await discovery, which would allow a fuller interpretation of the post medieval period.

The legacy of World War Two is clear to see in Poringland as a number of defences were erected and still remain in some form. Some of these such as the Type 22 pillbox in Mill Close (NHER 31129) were presumably intended to protect the radar tower to the north. The ventilation of an underground ‘buried reserve’ (NHER 32836) has also been noted 300m northeast of the radar and may have related to its defence. Aerial photography has also shown marks in a field a short distance northwest of Spruce Crescent that likely indicate the presence of a searchlight battery (NHER 34192), which would have highlighted any aeroplanes approaching the radar and main areas of habitation. A 1940 Home Guard Shelter (NHER 18232) has also been discovered to the southern extremity of the village, overlooking the approach along the Bungay road. However, perhaps the most poignant record of the wartime is the fact that the remains of a crashed Blenheim IV Z7304 aeroplane of the 18th Squadron landed here (NHER 13674). A tragic collision with the Stoke Holy Cross radar pylon wiped out the entire crew including Kenneth Thomas Tagg, a Met Forecaster based at RAF Wattisham.

Thus concludes the archaeological overview of the parish, and any interested readers should consult the individual records for more information.

Thomas Sunley (NLA), 11 December 2006.

Further Reading

Brown, P. (ed.), 1984. The Domesday Book (Chichester, Phillimore & Co.)

Norfolk Federation of Women’s Institutes, 1990. The Norfolk Village Book (Newbury, Countryside Books)

Rye, J., 1991. A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place Names (Dereham, The Larks Press)