Great Yarmouth started to recover from the depression of the late Medieval period in the late 16th century. The reasons for Yarmouth's continued depression had included a drop in trade, loss of herring industry to the Low Countries and the silting up of the Havens. Added to that was the cost of Yarmouth's town walls. Yarmouth's walls were effectively obsolete by the time they were finished, in 1390. Cannon had already been in use in warfare for some time (indeed, Charles IV of France had defeated the English at La Réole in 1324 using cannon). By the mid 15th century, massive artillery pieces such as Mons Meg rendered Yarmouth's walls useless. While Yarmouth had acquired some cannon by the start of the 16th century, it was not until 1539 that these were put into any order. Three earth bulwarks were built along the South Denes, covering the Yarmouth Roads and the haven mouth. No traces of these works survive. Indeed, they were declared nearly useless by the Duke of Norfolk in 1545. As if to prove this, a French privateer sailed past the bulwark in 1546 and captured an English merchant ship in Yarmouth Roads. The Duke of Norfolk also described the town wall as "the weakest walled town he ever saw" (Kent, 1988, 195). The duke ordered the clearing of the moat, and the reinforcing of the wall. While Kent states that "with bucket, basket and spade they levelled the sand dunes, dug out the moat and heaped up earth and sand behind the wall" (Kent, 1988, 197), boreholes drilled as part of the Great Yarmouth Archaeological Map showed that the majority of the rampart appeared to have been built of domestic rubbish. It is possible that the domestic rubbish recovered from the borehole (detailed here) originated as rubbish thrown into the moat, then emptied behind the walls as part of the reinforcing process. The reinforcing process was repeated several times, in 1557 and 1587, and remains as a ridge of high ground on the eastern edge of the walled town, visible in the Great Yarmouth deposit model, and on various historic maps of the town. Parts of the rampart survive in the churchyard of St. Nicholas Church.

The wall was not thick enough to mount artillery upon it, so several gun platforms, called Mounts, were constructed. The first mount was on St. George's Plain, underneath St. George's Church, and was built in 1569. It is visible on the 1588 map of Great Yarmouth in the British Library (Shelf Mark Cott.Aug.I.i.74) as a large earth mound, straddling the walls, with several cannon mounted upon it.

This was built into the New Mount in 1588, and traces of it can still be seen. The South Mount was built in 1570, as a small earth mound with two cannon mounted upon it. The Main Guard was also known as the Mount, and was built around 1626, in response to a number of raids from pirates. Excavations around the area of the Main Guard uncovered evidence of the 16th century ramparts, overlain by a much wider cobbled surface, presumably intended to mount artillery pieces. Overall, the ramparts and Main Guard has been raised 3.5m (11.5 feet) (Emery, 1998, 7).

At the start of the Civil War (1642), Great Yarmouth declared for Parliament, and set about renovating the defences. A large ditch and earthwork were constructed to the North of the town, and ditches and earthworks to the south were renovated. The northernmost defences remained in place until the 19th century, and are visible on several maps of the period, including Faden's map of 1797 (although, interestingly, not on Paston's map of 1668). Boreholes drilled as part of the Great Yarmouth Archaeological Map recovered waterlogged material and the remains of reed plants in the area of the moat.

Yarmouth built a new fort at the haven entrance in 1653, during the First Dutch War. The fort does not seem to have been a serious fortification: four ships were taken by a pirate under its guns, in 1654, and the fort had to be repaired in 1660. Part of the fort collapsed into the sea in 1832, and the remainder was demolished in 1833.

Three batteries (the North Star, South Star and Town batteries) were built in 1781, during the American War of Independence, with an additional battery sited in Gorleston. The Gorleston battery was demolished around 1816, and the site is under the junction of Upper Cliff Road and Cliff Hill. The Town battery was sold in 1859, and now lies underneath the houses on Marine Parade, between Paget Road and Euston Road. The North and South Star Batteries were repeatedly re-armed, and kept on until 1898, when the North Star battery was demolished, to make way for Collingwood Road. The South Star battery was finally demolished in 1924, and the site is now occupied by Harboro Crescent.

One factor unites Yarmouth's defences: with the exception of the battery on Gorleston cliffs, all of Yarmouth's defences were remarkable in their uselessness: the wall was built to withstand a pre-cannon assault, after cannon had been used in battle. The bulwarks built in 1539 were vulnerable to attack by raiding parties and too far from the town to be reinforced (not to mention the attack by a French privateer that they failed to prevent). When it was first built, the Mount caused part of the wall to collapse, and provided an easy method of ingress, should the town ever have been assaulted. The Harbour Fort failed to protect shipping in Yarmouth Roads. In fact, the fort was one of the few Yarmouth defences that was actually tested: it was successfully stormed in 1688, by a mob from the town. The North, South and Town batteries were under armed and badly sited. The South Star battery failed to protect the town against German raiders in November, 1914. It is lucky for Yarmouth that its defences were never properly tested. Ironically, the only battery that was sited in a position to defend the town or Yarmouth Roads was the shortest lived: the battery at Gorleston overlooked Yarmouth Roads and the haven entrance, yet was first to be demolished at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The majority of the defensive works around Yarmouth were, however, highly visible from the town, and had a profound effect on morale in times of crisis.

In the First World War, Yarmouth became a naval port, and a Royal Naval Air Station was built on the South Denes. Several zeppelin were shot down by aircraft from this station. RNAS Yarmouth was equipped with seaplane ramps and a grass airstrip, and deployed both seaplanes and conventional aircraft. The area became a landing site for civilian seaplanes after the war. The South Star battery was reinforced by a battery in Gorleston and several anti-aircraft batteries. Anti-invasion defences were also built

(such as the two pillboxes, 18493 and 18494, visible from the A47).

Yarmouth was heavily defended in the Second World War by a network of batteries, pillboxes and other defences. Most of these have been demolished, but some pillboxes, such as that on North Drive survive. As with the rest of Yarmouth's defences, they were fairly ineffectual, and did not prevent Great Yarmouth being heavily bombed, and the anti-invasion defences resulted in the beaches being unsafe into the 1950s (Kent, 1988, 222).

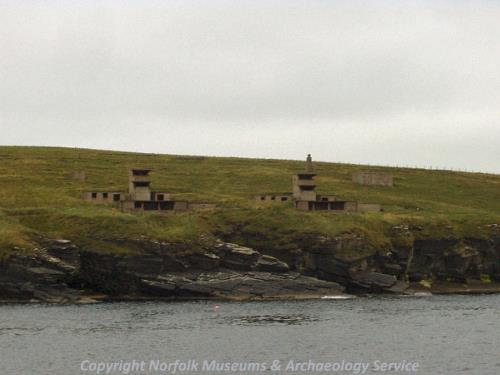

None of Yarmouth's batteries survive, but they were built to the same pattern as these batteries at Hoxa Head, South Ronaldsay, to cover Scapa Flow.

Click here for the Great Yarmouth bibliography.