Research and development into military aviation was under way as early as 1878 at Woolwich Arsenal, and a balloon factory had existed on a number of sites since shortly after that time. The first army military aerodrome was built on Salisbury Plain in 1911.

In 1914, at the start of World War One, there were only seven completed aerodromes in the whole of Britain. By its conclusion, there were 301 aviation sites, serving the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). The Royal Air Force (RAF) did not come into existence until 1918 as an amalgamation of these two arms.

Of these, some thirty fields were established in Norfolk, ranging from stations with many aircraft, to simple landing grounds equipped with only a telephone and storage shed. Runways were of grass, and it was Norfolk’s relative flatness that made it a good place for aviation sites. Early airfields were primitive, with accommodation and hangars of canvas. At the beginning of World War One, home defence was the responsibility of the RNAS, and many of the airfields were “night landing grounds” for anti-zeppelin actions. However, after bombing raids by German “Gotha” bi-plane bombers, in 1916 Home Defence duties were taken over by the War Office. Many sites were transferred to the bi-plane bombers. Airfields started to be divided into “Flight Stations” acting as area HQ’s and “Squadron Stations” as their satellites. These Flight Stations, together with the larger training depots, began to become more substantial, with more solid accommodation and hangers.

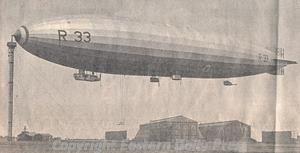

A 'Pulham Pig', an airship, at her mooring mast at Pulham airfield. (© Eastern Daily Press.)

In addition to airfields, the RNAS developed two specialist facilities; these were Airship Stations, and Flying Boat Stations. In Norfolk, the best known Airship Station was in Pulham (NHER

12413), from which flew the “Pulham Pigs” (as they were locally known). This was the scene of various experiments with airships, including long distance flights, and launching aircraft from special attachments on the ships. After the end of World War One, two zeppelins (surrendered by Germany as Prizes of War) were stored here.

The best known flying boat station was at Great Yarmouth (South Denes airfield) (NHER 13631) which was both a land and flying boat station. If the sea was too rough to land, flying boats could divert to Hickling Broad (NHER 8387) as a calm water satellite.

Structures on airship sites were characterised by massive hangars (or balloon sheds), gas generating plant, and mooring masts. Flying boat stations were more like conventional aerodromes, but with the addition of slip-ways. Whole books have been written about airfield buildings and architecture and it is not appropriate to go into detail here, particularly as few of the buildings from the period survive in Norfolk. For instance at Pulham, only a few remains and crop marks can be seen (although one of the huge hangars was dismantled and re-erected at another airship base in Cardington, Bedfordshire, where it remains. The flying boat station in Yarmouth has been demolished and built over, the last building going by 2004.

Another good example of this is at Narborough (NHER 13621), arguably the most significant World War One airfield in Norfolk. Originally an RNAS site, the field of 998 acres (huge by World War One standards, only the airship stations were bigger) was taken over by the RFC in 1916 and was developed as a major training station, with a satellite ground at nearby Marham (NHER 4510). Despite its importance, Narborough closed in 1920 and quickly fell into disrepair. Of over 100 buildings on the site, today there is nothing much to see except rubble. Instead Marham, the satellite station, became a major airfield after World War One, its original layout obliterated by later station development.

The conclusion of World War One saw a dramatic decrease in the number of airfields. In Britain, about 356 bases were abandoned, and by 1924 only twenty seven military ones were left. Generally, unless airfields were kept 'on strength', they did not leave much of a mark on the landscape after World War One. Many were ploughed up (e.g. Bayfield/Holt – NHER 13549) or otherwise returned to agriculture (e.g. Earsham NHER 13612). In some cases, so little remains that the actual location of the airfield is obscure (e.g. North Elmham NHER 29547 and Saxthorpe NHER 13625). In others, pretty much all that remains is a circular cropmark, of a whitewash/chalk circle which identified the landing area in World War One (e.g. Earsham NHER 13612 and Bayfield/Holt NHER 13549).

Few former airfields have been as comprehensively erased as Mousehold Heath in Norwich (NHER 12415) which has for the most part been covered by the Heartsease housing estate.

Married quarters built between 1928 and 1939 on Bircham Newton airfield. (© NCC)

A notable exception to this state of affairs was the airfield at Bircham Newton (NHER

1793) which was the only major site in Norfolk to stay operational in the inter-war years, having been opened in 1916. Initially a fighter station, then for bombers, it was in 1936 transferred to Coastal Command and underwent a major re-development. After much busy service during World War Two, the station was a training station for various RAF wings before being closed in 1962. It is now home to the National Construction College, which has preserved virtually all the old structures.

As already mentioned, the RNAS and the RFC were amalgamated into an independent Royal Air Force. This joining was not popular with the Admiralty and the Army, who had wished to keep control over their airborne arms. Therefore in the immediate post-war years, after the wholesale disposal of airfields, equipment and personnel, growth of the RAF was slow, and carried out against a quarrelsome background.

This continued until the mid-1930s when the increasingly uncertain situation in continental Europe led to serious expansion of the RAF. The first expansion phase saw the construction of Feltwell (NHER 4942) and the development of the World War One satellite base at Marham (NHER 4510).

Successive phases saw the development of Bircham Newton (NHER 1793 see above) and the building of permanent stations at Coltishall, (NHER 7697), Horsham St Faith (NHER 8137), Swanton Morley (NHER 2830), Watton (NHER 8908) and West Raynham (NHER 8685).

The architecture of these 'expansion era' sites is worthy of mention. It is an often overlooked fact that the inter-war years saw considerable opposition to many aspects of an independent air force. This opposition was partly based on arguments about the morals of air war (e.g. bombing civilians) and partly on concerns about the visual impact of many large airfields and associated buildings on the countryside.

As a result of the latter concern, much of the construction during the expansion period was carried out in consultation with the Council for the Protection of Rural England, and was of very high quality, adopting a neo-Georgian style. Expansion period airfields tended also to cluster all of their buildings (hangars, quarters, technical site etc.) into one area on the edge of the airfield: when World War Two commenced, this practice was changed, as groups of buildings in close proximity were vulnerable to bombing attacks. Airfields constructed during the war dispersed their buildings, sometimes over quite some distance. Also, bomb dumps were often concealed in nearby woodland.

A new feature appearing in these new airfields was the control tower, or watch office. Improvements in wireless technology in the 1930’s led to flying control becoming more sophisticated, and the watch office became increasingly important. A good example is to be found at Bircham Newton (NHER 1793).

In addition to the principal airfields, a new class of satellite aerodrome was introduced, where each parent field had one or more (usually two) satellites. This was designed to increase the effective capacity of the parent station without the expense of another fully equipped aerodrome. Examples of this include Bircham Newton (parent station) (NHER 1793) and its satellites, Docking (NHER 13551) and Langham (NHER 32435). Also see West Raynham (NHER 3685) and its satellites at Great Massingham (NHER 15168) and Sculthorpe (NHER 2007). Many of these satellites were developed into more substantial sites during World War Two (e.g. Sculthorpe and Langham).

Aerial photograph of Rackheath airfield. (© NCC)

On the outbreak of World War Two, the speed of airfield construction increased to a pace that is now difficult to imagine. Between 1939 and 1945 no fewer than 444 airfields were constructed in the British Isles, at a cost of over £200 million. In 1942 the peak of activity, a new field was being opened every three days. Also the scale of effort was enormous. For instance, the construction of Rackheath airfield (NHER

8170) near Norwich involved the laying of 504,000 cubic yards of concrete. Many of these airfields were 'Class A' bomber airfields with three concrete runways set in a triangular layout, with a concrete perimeter track, taxi-ways and dispersal points for aircraft. Examples of this layout may be seen at Sculthorpe (NHER

2007) and Langham (NHER

32435). It should, however, be noted that some airfields (e.g. Bodney NHER

5045 and Bircham Newton NHER

1793) remained grass only, with the added assistance of pierced steel matting.

Rackheath was one of a number of airfields built specifically for the Americans, who began operating from the UK in 1942. They rapidly built up a massive aerial force, mainly comprised of bomber and fighter units of the Eighth Air Force. U.S. Bomber Sites include Deopham Green (NHER 4260), which hosted B17 Flying Fortresses used in the daylight bombing campaigns from 1943, and Hethel (NHER 9522) which was a Liberator base. A small sample of further airfields include North Pickenham (NHER 2697), Old Buckenham (NHER 9235), where James Stewart served, and Sculthorpe (NHER 2007). An example of a U.S. fighter site is Bodney (NHER 5045) which had Thunderbolts and, later, Mustangs.

It should be noted that the above is intended very much as an overview. At the end of World War Two, Norfolk had some thirty seven major military airfields, and numerous subsidiaries. Those wishing to go further into what was a phenomenally busy and complex period should refer to the 'Further Reading' section at the end of this piece.

The last type of World War Two 'airfields' worth mentioning are 'decoy sites', or dummy airfields. These were constructed in the vicinity (but not too close to) genuine operational stations. Each real airfield had at least one decoy, some having more. There were two types of decoys, the 'K' type for daytime use, with fake wood and canvas planes (to correspond with the aircraft type on the real airfield), and 'Q' type for night use. 'Q' type decoys used mock flare-paths and runway lights. Some decoys filled both 'K' and 'Q' roles. Variations and even craftier deceptions based on these principles developed throughout World War Two. Many of the decoys were actually bombed, and on more than one occasion, allied aircraft tried to land on them, indicating the success of the deception. However, opinion is mixed as to their effectiveness. After the war, documents indicated that the Germans quickly caught on to the deception. There are several stories of dummy bombs being dropped on dummy airfields.

By their nature, decoy sites have hardly left any trace, but infrequently there remain the old control bunker or generator building. Examples of this include Wormegay (NHER 32381), a 'Q' site, and North Tuddenham (NHER 15019) a 'K'/'Q'.

A brief word is necessary here about airfield defence, although it could form a separate piece in itself. Passive defence included initially camouflage, trenches, gas decontamination centres (e.g. at Bircham Newton NHER 1793) and sand-bagging. However, during the Battle of Britain, as all over the country, there appeared gun posts, pillboxes, anti-aircraft guns (for example at Watton NHER 8908) and extensive barbed wire entanglements.

A defensive position unique to airfields was the Pickett-Hamilton Fort, a circular sunken concrete pillbox. This remained flush with the airfield’s surface to allow movement of aircraft, but could be manned and raised to allow firing in the event of ground attack. These are rare survivals, but examples can be found at Horsham St Faith (now Norwich Civil Airport) (NHER 32454) and at Swanton Morley (NHER 2830).

At the end of World War Two the huge airfield construction programme came to an end. Indeed this had begun some time before. Most airfields were closed down and eventually sold off. Some were returned to agriculture, in which case survival of the airfield remains varies. For instance, Docking (NHER 13551), a grass airfield is now agricultural, but some of the remaining buildings are used for storage. In contrast, Matlaske (NHER 6689) has been entirely erased, save for traces of the perimeter track.

In other cases, the runways have been grubbed out for hardcore, but technical sites, and other buildings have been taken over by industry (e.g. Rackheath NHER 8170).

Quite a few airfields with concrete runways became in later years part of that particularly Norfolk enterprise, Bernard Matthews Ltd. The runways form foundations for many rows of turkey sheds. Examples are at Weston Longville, known as ‘Attlebridge’ airfield (NHER 3063) and Langham (NHER 32435).

Bircham Newton (NHER 1793), as mentioned earlier, is almost unique, in that most of its buildings survive.

Still other airfields (or parts of them) have been taken over by gliding clubs (e.g. Tibenham NHER 23222) and private aero clubs (e.g. Shipdham NHER 2773).

For those airfields remaining operational after World War Two, the ensuing Cold War and the introduction of jet engines led to several developments. Runways were strengthened and lengthened to accommodate both jet fighters and British and American nuclear deterrent bomber force. Operational readiness platforms, hard standings and concrete dispersal areas became standard.

Increased reliance on electronic navigation aids led to the building of technically advanced control towers.

The threat of nuclear attack by missiles in the mid-1950s led to fundamental changes in defence policy to perceived threats. As a result, early warning by radar technology progressed rapidly, with specialist radar stations proliferating (e.g. Neatishead NHER 31218).

With a fast, high flying enemy, anti-aircraft batteries became obsolete, and instead Bloodhound surface to air missiles were deployed on airfields. A Bloodhound site may be seen at West Raynham (NHER 3685).

In the late 1950s, pending the development of NATO’s inter-Continental Ballistic Missile, an intermediate range missile was deployed as a nuclear deterrent. Known as Thor, this was the only fixed launching system ballistic missile to be based on British soil. In Norfolk, the missile was deployed at Feltwell (NHER 41288) and North Pickenham (NHER 2697), and the distinctive remains of their launch sites are visible. They were discontinued in 1964.

Today, only Coltishall and Marham survive as Frontline Operational Stations in Norfolk and Coltishall closed in 2006. Other stations, such as Feltwell are in use as tracking stations. In these post-Cold War times, it remains to be seen what the future holds for those airfields that are left. For instance, it recently emerged that Bernard Matthews Ltd., is moving towards abandoning its concerns on airfields, due to changes in the economy and farming practice.

From the 1930s, airfields have been extremely complicated developments, and there have been many detailed publications on both the sites and their history. It is possible to go into such detail that volumes could be written about one airfield alone. Therefore this is very much an overview, and those with an interest can delve a great deal deeper if they wish.

Pieter Aldridge (NLA), May 2005.

Further Reading

Bowyer, M., 1979. Action Stations. 1 Wartime Military Airfields of East Anglia 1939-1945 (Cambridge, Patrick Stephens).

Dobinson, C.S., 2000. Fields of Deception (London, Methuen).

Fairhead, H., 1992. Norfolk & Suffolk Airfields (Bungay, Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum).

Lowry, B. (ed), 1996. 20th Century Defences in Britain (York, Council for British Archaeology).

McKenzie, R., 2004. Ghost Fields of Norfolk (Guist Bottom, Larks Press).

Pope, S., Airfield Focus – 9. Swanton Morley (GMS Enterprises).