As soon as the Romans arrived in Britain the establishment of forts was vital if they were to assert themselves effectively. The Boudican rebellion resulted in a number of Roman settlements being burnt to the ground, so the addition of forts in East Anglia were vital if the rebellion was to be quashed. Most Roman forts would have been inhabited by an array of troops from different backgrounds imported from all over the continent, but later in the Roman occupation even native Britons could be found inhabiting them, having adopted the Roman way of life.

Brancaster Roman Fort (NHER 1001)

Cropmark evidence around the 1830s first drew attention to the site of the Branodunum (Brancaster) Fort, and in the ensuing years various excavations turned out Roman material and finds. It is believed that the fort, probably constructed 225-250 AD, replaced an earlier construction. The garrison included units from Gaul and Dalmatia. Finds within the fort suggest it was occupied around the third and fourth centuries AD.

A Roman gold finger ring set with a cornelian intaglio depicting a portrait bust from Brancaster Roman fort. (© NCC)

The fort’s plan is quite conventional, situated on a ridge with a rampart enclosure and stone wall surrounded by ditches. It has gateways in the centre of each wall on all four sides, with guard chambers connected to them; each corner of the fort’s wall is rounded with internal turrets.

The walls of the fort have deteriorated over time. They were demolished in 1770 and with the materials were re-used in the construction of the Great Malthouse at Brancaster Staithe (NHER 1377).

Finds from the fort include a silver ring, knife, bone and ivory pins, deer antler, tiles, pottery, coins and oyster shells. The consumption of oysters was pretty common for the Romans, who had a keen taste for fish. The presence of oyster shells whilst fieldwalking is usually a good indicator of Roman presence in the area. Another excavation uncovered the remains of six or seven individuals including a child. A gold ring was also found on site, showing two heads, with an inscription reading VIVAS IN DEO (translated as 'live in God'), of Christian origin.

Thornham Fort (NHER 1308)

Thornham Roman Fort was discovered in 1946 when an aerial photograph identified signs of an enclosure indicated by cropmarks. It soon became apparent that the site of the fort was also the site of Iron Age structures, with cropmarks marking out the location of an Iron Age fort and roundhouse. Amongst the Samian sherds, traces of Roman building material and other finds were a coin showing Antonius Pius, a chalk block apparently used as a gaming board and over five hundred oyster shells.

Aerial photograph showing the cropmarks of Thornham Fort. (© NCC)

Again, the fort is of typical rectangular design, with each of the corners rounded. Interestingly, pottery found sealed beneath the rampart footings implies that the fort would have been constructed around the first century AD by native engineers familiar with Roman military techniques. It is also likely that the incentive behind it’s construction was the aftermath of the Boudican revolt of AD 61, as the Romans prepared to make a move against the remaining rebels.

The coins and pottery found in the fort both suggest second century occupation, although inside the enclosure five Christian Saxon bodies were found, that of a youth around seventeen years old, a young man, a child of about nine to ten years of age, a baby and an infant with yellow beads by it.

Dating of the ramparts and their chalk remains confirmed occupation of the fort in the first century. After AD 61 the fort was abandoned only to be re-occupied between around 120 to 200 AD. A further fifteen Christian burials were also found along with grave goods.

Woodcock Hall Roman Settlement and Fort (NHER 4697)

Iron Age pits, Roman settlement, a crematorium, two forts, a road and even medieval to post medieval evidence of a moat, pit and brick kiln have all been found at Woodcock Hall, Saham Toney.

Aerial photograph of the 2nd century AD Roman fort at Saham Toney. (© NCC)

Inevitably the excavations uncovered a wealth of finds, growing steadily in abundance. In the 1930s to 1960s tesserae were found along with Roman sherds and the odd Iron Age or Roman coin. Excavations in 1971 revealed pits, a brick kiln, more pottery and other Roman finds.

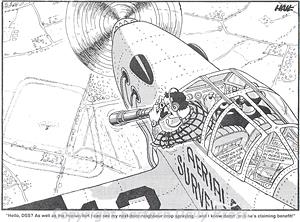

Cartoon depicting the discovery of Saham Toney 2nd century AD fort. (© Eastern Daily Press.)

The following year sherds, tile, timber and metalwork were found along with a Palaeolithic hand-axe. Then in 1972 a Roman coin hoard was found, and the excavations from then onwards yielded an impressive number of artefacts, some of which were of Iron or Bronze Age origin, but predominantly Roman.

Judging by the nature of the finds it seemed the original fort was replaced by a larger one built as a consequence of the Iceni rebellion of East Anglia. The second fort was manned by an estimated eight hundred legionaries and cavalry. Adjacent to it was found another smaller encampment, probably used for housing horses for the cavalry.

The Woodcock site lies on Peddar’s Way, a major Roman road running across west Norfolk, and therefore a successful trading route in the region.

Caister-on-Sea Roman Shore Fort (NHER 8675)

A Bronze Age ring ditch, a Roman bridge, corn drying kiln, drain, floor, hearths, a hypocaust, mausoleum, lime works, an inn and a fort have all been found at Caister-on-Sea. Digs began in one way or another around 1837 when skeletons, coins and sherds were found in a pit lined with Roman tile, and continued up until 1997.

The ruins of the Roman fort at Caister on Sea. (© NCC)

The fort itself is situated on what was the shoreline of a large estuary extending southwards inland. What remain are the western part of the interior of the fort and portions of the defences. The fort was probably subdivided into a rectilinear grid of streets. It’s construction is dated to around the early third century AD and finds range from items of military equipment but also more personal items including hair pins, which is evidence of women being present within the fort, possibly from the late third century onwards.

Towards the end of the second century AD, the coasts along the southeast of England came increasingly under threat from Saxon raiders, so defence structures in these areas were common, as they were in many other areas across Roman Europe. A common feature of the shore forts were their impressive stone wall defences, backed by an inner earth mound, surrounded by ditches. There would have been parapets and turrets dotted along the defensive structure at intervals.

The Caister-on-Sea fort is a relatively typical shore-fort in terms of its design. The abundance of information contained within the fort’s archaeology has been priceless in its assistance in dating the fort. Surviving shore forts are not very common, and their limited numbers mean those that have survived are of national importance, as they communicate a vast amount of valuable information on the Roman’s strategic military policies during their periods of use.

Nic Zuppardi (Notre Dame High School, Norwich), September 2005.