Deposit models are not uncommon in urban archaeology: they are a method of estimating the depth and nature of archaeological deposits across an area, and are usually derived from past excavation evidence. In Great Yarmouth, however, there is very little in the way of excavation evidence (e.g. Rogerson, 1976). Instead, the Great Yarmouth Archaeological Map created the model from 142 boreholes

The boreholes were drilled with a Dando Terrier window sampler, which is a compact, self powered drilling rig ideal for the streets and rows in Great Yarmouth. Drilling was carried out by Norfolk County Laboratory, part of Norfolk County Council. The sampler collects one-metre length samples of soil (tubes). After each tube was extracted, the sampler was returned to the borehole for the next metre, so the tubes for each borehole were 0-1m, 1-2m, 2-3m and so on, up to a depth of six metres.

The tubes were sealed, and taken back to the laboratory for analysis. The position and height above Ordnance datum of each borehole was recorded in three dimensions.

Back in the lab, the tubes were opened and examined for details about the soil throughout the full length of the borehole, and the location of any artefacts is noted. Distinct layers were noted and the exact position and depth of the top and bottom of each recorded electronically.

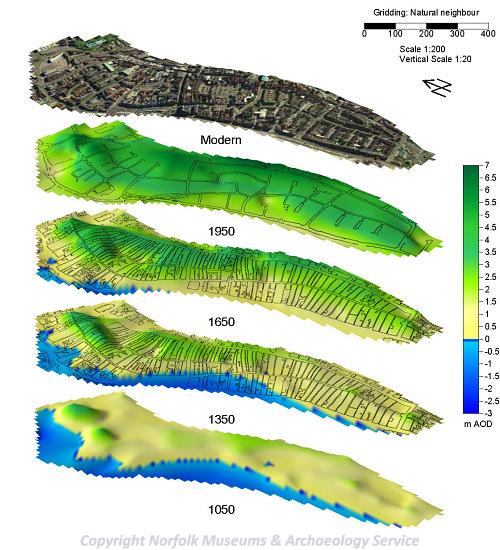

Obviously, most archaeological layers recorded in one borehole do not stretch far enough to be visible in other boreholes. However, we can match layers of similar date, leading to the creation of a series of former land surfaces (palaeotopographies).

The land surfaces formed from the deposit model data are not exact: we have no way of knowing if a borehole has gone through a pit or a well, giving an artificially deep reading. However, the deposit model is designed to give a general idea of the depth and nature of archaeological deposits, rather than an exact depth at an exact spot.

The deposit model has been constructed by interpolation of all available borehole data. The model also includes information from excavations around the town, such as the Norfolk Archaeological Unit excavations in Fullers Hill, in 1974 (Rogerson, 1974).

Layers were dated using artefacts recovered from the boreholes. Pottery fragments were dated by type, while wood was dated by radiocarbon dating.

The different layers in each borehole log were matched up to form a series of palaeotopographies.

We found that we could identify four man-made layers, and three natural layers:

- modern: anything after about 1950AD

- post medieval: anything after about 1650AD

- late medieval: anything between 1350AD and 1650AD

- early medieval: anything between 1050AD and 1350AD

- windblown sand: this occurs before and during the early medieval period, mostly on the eastern half of the town

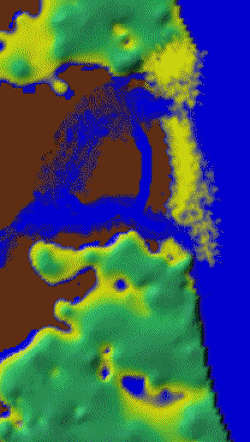

- estuarine mud: this occurs on the western half of the town. Most of it predates the early medieval deposits, but some may be as late as 1600AD

- marine sand and gravel: these predate the Medieval deposits, and are predominantly of the North Denes formation

The deposit model shows a distinct series of geological and archaeological phases. The area where Great Yarmouth now stands started out as the mouth of a great estuary. Since the last ice age, a south bound current has laid a spit of sand across the mouth of the estuary, from the north end to the south. The sand spit blocked off the estuary, leading to the formation of the peat that was cut to make the Broads. The sand spit was breached by the sea, and left as either a low tidal island or a shoal until about 1300 years ago, when it gradually took shape. When it was first occupied, probably some time in the tenth century, it was a low lying sand spit, most of it about 1m (3 feet) above sea level.

Throughout the first few centuries of habitation, life on the sand pits must have been precarious. Large drifts of windblown sand buried houses, and moved sand dunes. By the time the walls were built, in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, the ground was over a metre higher, from a build up of windblown sand, demolished houses and rubbish.

People continued to bury their rubbish in the town until about 1600 - we have relatively few domestic finds from after that date. This suggests that night soil men (bin men) were employed after 1600.

Click here for the Great Yarmouth bibliography.