Iron was first used in Britain around the 7th century BC. The procedures for making iron objects are complex. It takes several stages of production to reach a finished artefact. The process begins with the extraction of iron ore.

Iron Ore Extraction

The geology of Norfolk dictates where suitable sources of iron ore could be found in the past. Iron ore is relatively abundant in Britain and was available in most counties. In Norfolk some of the sands laid down in the Lower Cretaceous period in the west part of the county are cemented together by iron oxides to form carstone. This iron-rich red sandstone is likely to have been used as an iron ore. In the east of the county iron rich minerals within the sands and gravels laid down just before the late Cenozoic Ice Age form nodules and areas of ‘hard pan’ that could also be smelted into iron. It is also possible that other smaller deposits of ore were found and used up in the past.

Excavation of the ironworking pits between Weybourne and Runton.

The extraction of these iron ore nodules may leave holes or pits in the ground. Over 1000 of these iron extraction pits have been recorded between Weybourne and West Runton (NHER 6280) on the north Norfolk coast. Archaeologists excavated some of these holes or pits in the 1850s. Every red circle on this map is an iron ore extraction pit. Similar pits can be seen on aerial photographs of Roughton Heath (NHER 38670).

After iron rich ores have been selected and dug up, they were, where possible, heated or roasted to reduce impurities. Although there are no clearly identified roasting pits in Norfolk it is possible that some of the pits excavated at Runton (NHER 6280) were re-used for this. After the ore had been heated it was then ready for smelting.

Smelting – Ore to Iron

Smelting turns the iron ore into metal. The waste products of this process are called slags. Different shapes and sizes of slag are used by archaeologists to identify how and when the iron was smelted. Smelting slag has been recovered from many sites in Norfolk including Ingoldisthorpe (NHER 1553) and Middleton (NHER 3349).

The process of smelting was carried out in furnaces, the two main types being the bloomery and the blast furnace. The bloomery furnace was used from the Iron Age period until the around 1500 AD. Several have been excavated in Norfolk.

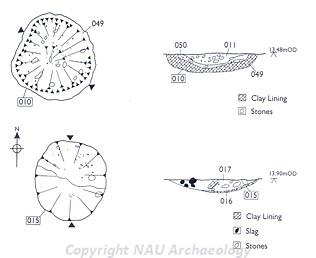

Early ironworking furnaces excavated at Aldeby. (© NAU Archaeology.)

Excavations in Aldeby (NHER 34099) revealed evidence for Early to Middle Iron Age iron working. Nine furnaces were excavated. These unassuming clay lined pits were probably used for smelting iron. They were found with Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age pottery and might be the earliest evidence for iron working anywhere in the country.

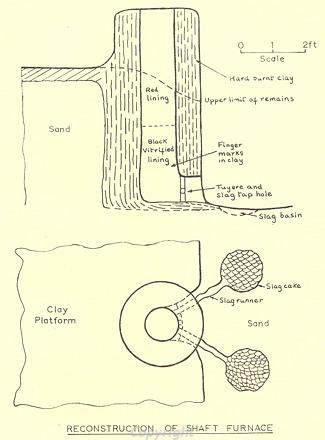

A 2nd century AD Roman iron smelting furnace excavated in the 1950s at Ashwicken.

A Roman iron smelting site was revealed during excavations in the 1950s in Ashwicken (NHER

3382). Furnaces and slag were excavated. Another Roman ironworking furnace (NHER 1008) has also been excavated at Scole. This was unusually complete and the excavation revealed parts of the shaft up to 0.4m high, a stoke hole and a pair of small depressions which were designed for slag to seep into. Excavation of the furnaces enabled archaeologists to work out how they worked.

A reconstructed ironworking shaft furnace from evidence excavated at Ashwicken.

Bloomery furnaces were exclusively fuelled by charcoal. They usually consisted of a cylindrical clay shaft between 1 and 1.5m high with a hearth or fire at the bottom of the shaft. The fire was lit and when the furnace was hot, roasted ore and charcoal were added to the top of it. To achieve a high enough temperature to smelt iron (between 1180 to 1540°C), air was forced into the furnace with bellows through a hole in the clay shaft at the base. This hole is called a tuyere.

The hottest part of the furnace was near the tuyere. This is where the liquefied slag separated from the solid iron and flowed to the bottom of the furnace. The iron particles formed a spongy lump called a bloom, which usually attached itself to the furnace wall just below the tuyere. It grew here until it started to interfere with the airflow. It was then removed, either from the top of the furnace or from a hole in the side. A bloomery furnace produces wrought iron – a solid bloom of metal that can then be reworked by hammering whilst it is hot into manageable lumps or shaped bars or billets.

Another example of a bloomery furnace has been found in Norfolk at West Runton, not far from the extraction pits described above. Excavations in 1964 uncovered iron smelting debris and furnace bases (NHER 6353). The metal working debris dates to the 10th and 11th century AD. A large piece of tap slag (slag which had run out of the furnace) was recovered.

Although bloomery furnaces were still being used, blast furnaces were introduced around AD 1500. Originally they were fuelled by charcoal, but by about 1750 they were being fuelled by coke. Coke is stronger than charcoal, so the height of furnaces could be increased without stack contents compressing and blocking the air blast. This meant that more iron ore could be converted into iron in one go. In addition the bellows for a blast furnace were powered by water rather than hand. This meant that higher temperatures could be reached. Higher temperatures meant that more of the ore was converted into iron – the process was more efficient.

The iron produced in a blast furnace is cast iron. As the temperature in the blast furnace was higher than in the bloomery furnace, the iron was actually molten. The iron ran out into moulds for ingots or objects like guns. The high levels of carbon in cast iron, however, makes it brittle, so it needs to be refined so that it can be hammered into shape by the smith. To do this the iron was re-melted in an open charcoal hearth. The carbon in the iron was removed and a bloom (just like the one formed in a bloomery furnace) formed in the hearth. The bloom, whilst still hot, was then hammered to remove most of the trapped slag and shape it into a bar.

Blast furnaces and refining hearths were used in the late medieval and post medieval period. Unfortunately none of these types of furnace have been excavated or recorded in Norfolk.

After the iron was smelted it need to be smithed to make it into an object.

Smithing – Iron to Object

The lump of iron formed at the smelting site would have been forged or smithed whilst hot to make it into artefacts. Smithing is a complex art and involves hammering, heating and quenching (plunging into cold water) the metal in a series of cycles of working. It may seem strange but these processes leave very little archaeological evidence – most smiths’ equipment was portable. Smiths were also generally tidy people who cleared up any mess or large bits of waste material (slag) they left behind. Slag was often put on the roads to create a hard surface to walk on.

The blacksmith's workshop in Heydon. (© Eastern Daily Press.)

One type of slag that smiths can’t remove from an area they work in is hammerscale. Hammerscale is the small sparks seen flying around when a blacksmith works or hammers an object. These small magnetic particles fall on the floor and are often the only clue that suggests blacksmithing has been going on. A gully and a pit in New Buckenham (NHER

40629) in Norfolk contained hammerscale suggesting that a blacksmith once worked nearby.

Several structures have been excavated between Austin Street and Norfolk Street, King’s Lynn (NHER 31393) including a blacksmith's workshop. The workshop was identified after archaeologists took soil samples to test for the presence of hammerscale.

At Kilverstone an excavation (NHER 34489) uncovered three circular Late Roman structures that were associated with blacksmithing. One structure contained a wooden pump, one of only two examples to be excavated in Britain. A blacksmith's hoard, including an anvil and tongs - tools of the trade, was found in a pit on the site.

Smithing practices have not changed substantially since the post medieval period. Smithing took place in a hearth or forge. There would have been a shelter protecting the hearth from the elements. The dim lighting under the shelter would have enabled the smith to judge the temperature of the metal.

The same techniques are still being used in Heydon today where a 19th century single storey brick forge (NHER 12729) is still in use.

Foundries - Industrialising the Process

The first known foundry in Norfolk was set up in 1797 by Robert Ransome. By 1801 there were three in Norwich and three in other areas of Norfolk. By 1845 White's Directory recorded 44 foundries in the county. Raw materials were imported (iron, limestone and coke) and finished objects such as agricultural machinery, railings and domestic goods produced. Many local foundries developed their own specialities. For example Cubitts foundry at North Walsham provided all the lock gear and balance beams used on the North Walsham and Dilham canal (NHER 13534).

The old iron foundry on Coslany Street, Norwich.

Unfortunately the buildings belonging to these fascinating firms have not yet been integrated into the NHER. Norfolk Landscape Archaeology does, however house the records of the Norfolk Industrial Archaeology Society that work hard to record industrial archaeology like the foundries before it disappears.

We are fortunate that they do so. Ironworking carried out in modern furnaces, forges and smithies helps us to understand the archaeological evidence for blacksmithing in the past and help us to recreate the processes by which our ancestors created iron from ore and objects from iron.

Katy Fullilove and Megan Dennis (NLA), 28 September 2006.

Further Reading

Scott, B.G. and Cleer, H. (eds.), 1984. The Crafts of the Blacksmith. (Belfast, UISPP Comite).

English Heritage, 2006. Archaeometallurgy. Centre for Archaeology Guidelines. (English Heritage).

Hutchison, P., 2006. ‘The Historical Metallurgy Society’. Available:

http://hist-met.org/, Accessed 28 September 2006.