After the Roman invasion new religions and gods were introduced. Native Britons already had their own deities. These old and new beliefs gradually became integrated. New Roman style temples were built and used by both Romans and natives.

Caistor St Edmund Roman Temple (NHER 9787)

In 1932 part of a temple wall was discovered in Caistor, not far from Venta Icenorum (NHER 9786). In 1949 full excavation of the site uncovered a Romano-Celtic temple.

A Roman seal box lid found at the site of a Roman temple at Caistor St Edmund. NWHCM 1929.152.X5:A (© NCC)

Finds on the site of the temple are as varied as they are numerous, with a spread of Roman coins ranging from the reign of Domitian to Constantine I, pottery, Roman sherds, tiles, metalwork and Neolithic worked flints. Amongst the more interesting artefacts uncovered were a trumpet brooch, a miniature iron knife, and an Early Saxon brooch.

Great Walsingham Roman Temple (NHER 2024)

Finds of Roman pottery and building material at Great Walsingham in 1950 indicated the presence of a significant archaeological site, as did cropmarks in the area. The finds on this site were also abundant. From 1984 onwards metal detecting recovered a large number of objects. these included a portrait bust of Minerva, a model of a three-horned deity, masks of Cupid and representations of satyrs. These indicate the presence of a Roman temple.

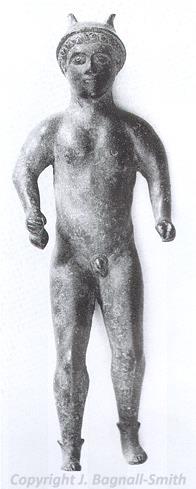

A Roman figure of the god Mercury found at the Walsingham Roman temple site. (© J. Bagnall-Smith.)

Votive material included three rings with inscriptions to the gods Mercury, Toutates and to the Matres Transmarini. Finds associated with the god Mercury around the temple site are so common that it is highly likely he was the most popular deity worshipped here. The cupid and satyr artefacts also suggest the presence of a cult to Bacchus.

Huge amounts of Roman metalwork were found. Amongst the metalwork was a make-up spoon, a snake bracelet and a large handle from a box or cauldron. Other finds included an iron knife, studs with Celtic style ornamentation and a circular decorative plate from a harness.

What stood out about the collection of artefacts was the number of brooches in immaculate condition. These also originate from various geographical locations, many are British but a higher percentage seemed to be continental in origin. These may have been votively deposited at the site.

Crownthorpe Roman Temple (NHER 8897)

When part excavations took place in 1959 on a cropmark in Crownthorpe, the regular rectangular foundation of a Roman temple was found. Tesserae, wall plaster, pottery, tile fragments, iron nails and a single coin were found that year on the temple site, as were traces of a veranda and cella wall. As with many sites of this sort, there are also traces of archaeology dated around the Iron Age, Late Saxon and medieval periods.

A copper alloy Roman cosmetic pestle from the Roman temple site at Wicklewood. The handle is in the shape of a duck. NWHCM 1983.43.9:A (© NCC)

After numerous excavations a rough plan of the temple was obtained. The temple was built out of flints and mortar with tile bonding courses. Nails found on site imply that timber was also used in the construction. The amount of tesserae found suggests that the floors of the temple were covered with mosaics.

In the centre of the site lay a mass of mortared flints, the function of which is unclear, though it is possible it may have been used as an altar platform or the base of a statue of a deity.

The presence of a temple is usually associated with other dwellings in the region, so it is possible there would have been settlements nearby but for a while none were detected. A Roman road ending abruptly in the Wymondham area supports the theory of a settlement as, obviously, it would have to have ended somewhere significant. Finally, a long term metal detecting survey yielded over one thousand Roman coins and other metal artefacts found around the site. It is suggested that these represent a Roman settlement presumed to have been active between 70 to 180 AD.

Due to the nature of the site's condition it isn’t easy to pinpoint an exact date of occupation or construction of the temple itself, but any time in the vicinity of the second or third century AD seems likely, with it’s destruction possibly taking place some time in the reign of Constantine the Great.

Nic Zuppardi (Notre Dame High School, Norwich), September 2005.