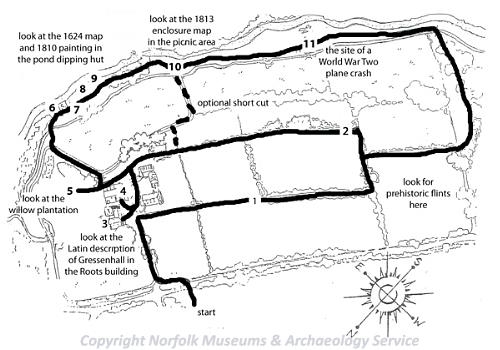

A map of the Gressenhall Farm Heritage Trail. (© NCC)

Take a walk around Gressenhall Farm and discover prehistoric worked flints, a medieval chapel and the site of a World War Two plane crash. The walk is just over two and a half kilometres and may be muddy in places. Along the way you can look for prehistoric worked flints, examine ancient maps and research old paintings of the landscape.

Please obtain a ticket from the shop before following the trail and keep to the paths.

1. Prehistoric Gressenhall

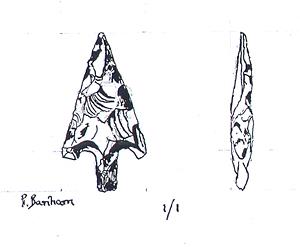

Beaker period barbed and tanged flint arrowhead from Brundall. (© NCC)

Worked and burnt flints found on these fields (NHER

29257,

29249,

29234,

29233,

28577 and

28576) indicate that there were people here thousands of years ago. These finds include a barbed and tanged arrowhead and worked flint flakes. You can see some examples of flint tools in the 'First Farmers' gallery in the workhouse. As you walk along the field see if you can find any more worked flints.

Prehistoric flint pot boilers from Middleton. (© NCC)

A number of prehistoric pot boiler sites, or burnt mounds, have also been found in the parish. Pot boilers are pieces of burnt flint that have been used for cooking. They were heated on a fire and then the hot stones were dropped into water to heat it up.

2. Roman Gressenhall

Pieces of Roman pottery (NHER 29243), a Roman quern (NHER 11356) and a Roman coin (NHER 22808) have been found in Gressenhall. None of these finds come from the farm itself. There was a 1st century AD Roman fort at nearby Swanton Morley. So we know the Romans were around but there isn’t any evidence for a Roman settlement here.

3. Saxon Gressenhall

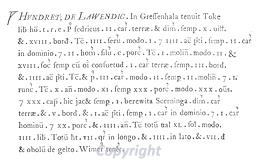

The Domesday Book entry for Gressenhall.

The village of Gressenhall is first recorded in the Domesday Book that dates to 1086. The name Gressenhall comes from Old English and means 'a grassy or gravelly nook of land'. William of Warrenne held land here. He was one of the richest and most powerful noblemen in the country after the Norman conquest and the builder of Castle Acre planned town (NHER

43123) and castle (NHER

3449). His holding in Gressenhall included meadows, two mills, woodland and sheep, goats, pigs and cattle. You can see the Domesday Book entry and a translation in the Roots building.

4. Medieval Gressenhall

In the 13th century this part of the parish of Gressenhall, where the farm now stands, was known as Rougholm. It was here that the de Stutevill family, the lords of the manor of Gressenhall, founded a chapel (NHER 2822) that was dedicated to St Nicolas (a popular saint in Norfolk, more well known today as Father Christmas!).

The chapel was originally founded as a college of priests, overseen by a master, and we know that the first master's name was Adam de Skyppedam (possibly from Shipdham). Otherwise, the medieval history of the chapel is a bit obscure but we know that in the 15th century there were a number of buildings here including a barn and a larger building that has a hall and a solar chamber for the master. It is unclear from the medieval documents whether the original chapel was a separate building or simply a room within the large building where the master and the other priests lived.

If you go into the barn you can see some large blocks of stone in amongst the bricks and flint. These are reused stones, probably taken from the medieval buildings, so at least one of the chapel buildings must have been built of stone. One block has a carved edge suggesting the building might have been quite ornate.

By the time of the Reformation in the early and mid 16th century, the chapel was a poor and humble institution and it had no goods or church plate of any value. It escaped the first wave of Henry VIII's Dissolution in the 1530s, but it had been dissolved by the 1550s and the buildings and land became a secular manor house and farm.

5. 16th century Gressenhall

Part of the modern farm is now planted with willows and is managed as a coppice (NHER 29233). Coppicing is a form of management when the trees are cut right down almost to the ground every seven to ten years. This encourages the trees to regrow, producing long thin poles of wood which are useful for things like making fences. In the early 16th century, and probably in the medieval period too, some of these fields, close to the river, were planted with alder trees. A man was fined in the manorial court in the early 16th century for cutting down some of the alder trees. Trees like alder and willow grow best in damp land, and they were probably managed by coppicing in the medieval and post medieval period just as they are today. The poles of alder that would have been grown here had wet pulpy middles that were scooped out, leaving a hollow pole, excellent for use as a water pipe. The many medieval monasteries in Norfolk often had complex water management systems and would have needed miles of water pipes. Some of them might have been supplied from the alder coppice at Gressenhall.

6. 17th century Gressenhall - the land

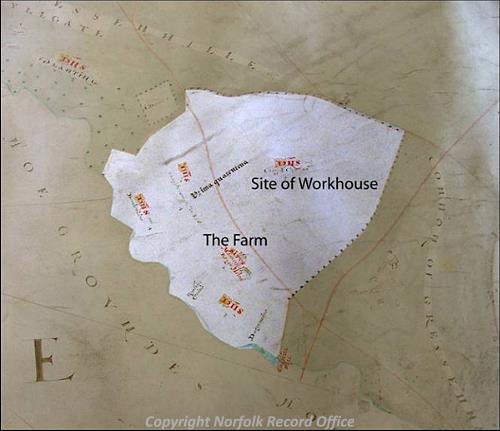

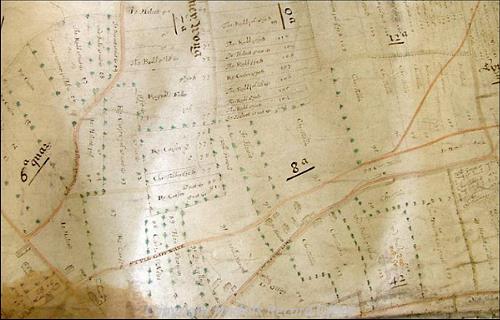

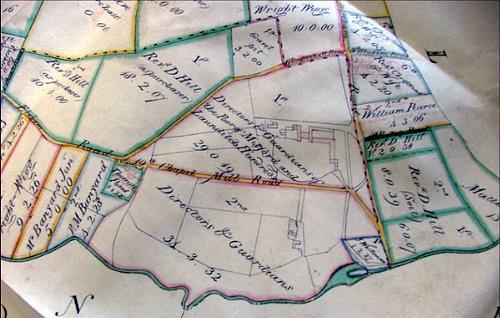

Map of the area of Gressenhall Farm drawn in 1624. (© Norfolk Record Office.)

The map of the farm shown above was produced in 1624. You can see the outline of the land held by the farm. The manor house is shown to the south of the road. To the north of the road is where the workhouse now stands. This outline of the farm persists to the present day because it was this block of land that was given to the workhouse in the late 18th century.

Detail of the 1624 map of Gressenhall showing strip fields just north of the farm. (© Norfolk Record Office.)

In the early 17th century there were over one thousand strips in the open fields of the parish and the map shows several strip fields intermingled with small enclosed fields. A strip was about as wide as the piece of grass between the boardwalk and the river. The landscape looked very different to how it does today. It would have been much more open, like the huge prairie fields of the Fens and West Norfolk today, with few hedgerows and few obvious boundaries. In Gressenhall there were three large open fields each divided up into hundreds of these small strip fields. Even though everyone had their own strips, the open fields were farmed communally and regulated by the manorial courts.

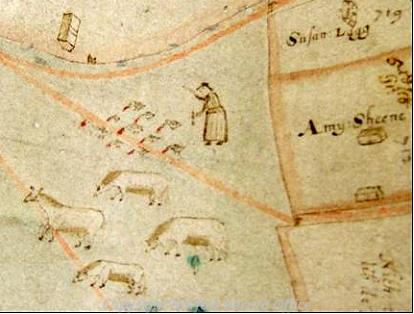

Detail of the 1624 map of Gressenhall showing pigs on the common. (© Norfolk Record Office.)

In the 17th century the farm was surrounded by a large common. This common land was very important for local people. The 1624 map shows local people keeping pigs, geese and cattle on the commons which would have been areas of grazing land with some trees.

Detail of the 1624 map of Gressenhall showing geese and cattle on the common. (© Norfolk Record Office.)

It was difficult to keep any animals on your strips in the open fields when they were under crops (which would have been eaten). You had a responsibility to keep your animals off neighbours' strips, which was diificult to do on such a small space. Keeping animals on the commons was not without problems though. It was difficult to keep your animals under control, disease could spread between peoples' animals and it was hard work to catch them.

From the late medieval period people began to enclose small parts of the open fields, a process known as piecemeal enclosure. This usually meant getting together with your neighbours and swapping strips in the open fields so that you could build up a consolidated block of land that you could then fence or hedge, forming a small field. On the 1624 map there are several small hedged fields next to the strip fields. By doing this people still had strips in the open fields but also had somewhere secure and practical to keep their animals. In fact an excavation carried out in 1999 on the site of the black barn revealed several late medieval ditched field boundaries (NHER 28575), probably small enclosed fields close to the farm.

7. 17th century Gressenhall - the buildings

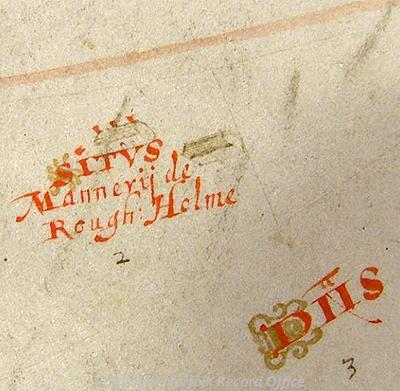

Detail of the 1624 map of Gressenhall showing the manor of Rougholme. (© Norfolk Record Office.)

The detail of the map shows the manor house and another building next to it. If you look at the farmhouse today you can see that the farmhouse and barn are in approximately the same positions as the buildings shown on the 1624 map.

Francis Blomefield, who wrote a history of Norfolk in the early 18th century, described the remains of the chapel as a long narrow building, most of which was still standing in the 18th century. It seems likely that the building shown on the 1624 map, on the site of the present barn, may be the remains of the medieval chapel, or the medieval hall where the master and priests lived.

The manor house shown on the map has a tiled roof and three chimney stacks. An early 17th century survey described the site as having a 'mansion house, barns, stables, orchards and gardens'.

The present barn and farmhouse are unlikely to date back to the medieval period. The reused blocks of stone in the barn suggest that the medieval buildings were demolished, perhaps after 1624 when the map was made. The present buildings erected in the 17th or 18th centuries on the same site as the earlier structures.

8. 18th century Gressenhall

A painting of Gressenhall Mill and workhouse dated to 1810. (© NCC)

The buildings we can see today in the farmyard were mostly constructed in the 18th century. The workhouse (NHER

2819) itself was built in 1777, one of the earliest 'Houses of Industry' in Norfolk. The building was in use as a workhouse until 1948. Look at the early 19th century painting of the workhouse in the pond dipping hut. You can find out more about the history of the workhouse in the displays inside the main museum building.

9. 19th century Gressenhall - the mill

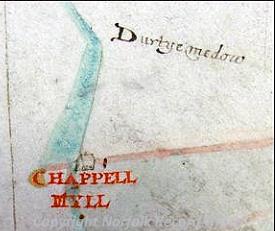

Detail of the 1624 map of Gressenhall showing Chappell Mill. (© Norfolk Record Office.)

Through the trees you can also see a large white house, which is a former miller's house. The miller worked in a large 19th century watermill that was burnt down in 1914. There has been a mill on this site since the medieval period and it may also have been the site of one of the mills mentioned in the Domesday Book.

The medieval mill (NHER 12758) was timber framed and thatched (we know that because medieval accounts record repairs to the mill and the cutting of reeds from the mill pond to use as thatching materials). There is a building called Chappell Mill marked on the 1624 map. Unfortunately the map is too faded to pick out many details of the building. The painting of 1810 shows a timber framed and thatched mill. You can also see the buildings of the farm on the far left of the painting hidden among the trees.

The 19th century water mill before it was burnt down in 1914.

The 19th century watermill was one of the largest and most advanced in the area and was converted into a steam mill in 1847. When the mill caught fire in 1914 it took the Dereham Fire Brigade one and a half hours to get to Gressenhall. By the time they arrived the flames from the mill fire could be seen in Norwich.

The river and mill pond crop up fairly regularly in the records of the manorial court. One man was fined for fishing in the mill pond without a licence. Another was fined for putting hemp into the mill stream.

Hemp was an important crop in the medieval and early post medieval period. In order to make rope or cloth from hemp the fibres had to be separated, a process that involved rotting the hemp in water. This was a very polluting process and was prohibited in rivers and streams. Instead the hemp was rotted in small rectangular ponds known as retting ponds. Today many of these survive as earthworks and cropmarks (NHER 10210). One has been excavated in nearby Beetley (NHER 20564). In the 18th century the male inmates of the workhouse were set to work picking hemp and flax amongst other tasks.

10. 19th century Gressenhall - the land

The 1813 parliamentary enclosure map of Gressenhall. (© Norfolk Record Office.)

In 1813 Gressenhall was enclosed by an Act of Parliament. This meant that the landscape changed completely. Parliamentary enclosure fields are fairly large and have straight hedged boundaries just like the fields you can see on the farm today. By the time of enclosure the workhouse had been built and the farm was used to provide food and employment for some of the people living in the workhouse. The farmhouse itself was used as a workhouse infirmary during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

By looking at the 1813 enclosure map we can see that Parliamentary Enclosure had an immediate and dramatic impact on the landscape. The open fields and small enclosed fields were replaced by large fields with straight hawthorn hedges. This wholesale replanning of the landscape had a huge impact on local people who had grown up in the landscape. During the 19th century farming became increasingly efficient and mechanised and large tenant farmers were farming for profit rather than for subsistence. In the early 19th century the farm was tenanted out as it was no longer possible to run it with a dwindling labour force from the workhouse.

8. 20th century Gressenhall

Records show that an American Liberator aircraft crashed on the other side of the river (NHER 12801) at this spot on 27th March 1944, following a mid air collision with another plane.

Sarah Spooner (NLA), Summer 2006.