INTRODUCTION

Most of the images submitted here are my own work and represent the visual method of problem solving I employ as part of my research into the origins of Castle Rising Castle (NHER 3307), its local environment and areas spanning across the whole of East Anglia. I hope visitors to Norfolk Heritage Explorer website appreciate that the images and text represent a personal response to the site.

My work began in March 2002 as a routine record and physical re-appraisal of the castle keep as part of my new appointment as Head Custodian. Originally, I sought to establish a sound archaeological sequence for the construction of the keep and defences in the hope of understanding the practicalities of daily life within such a site. The main source for this analysis has been the site excavation report by Morley & Gurney (1997) which established a reliable sequence based upon dating evidence. In the process of investigation, three fundamental questions remained unanswered; primarily why here? Rising Castle apparently defends nothing, guards no crossings nor overlooks any area of strategic value. Second, why was the castle decorated like a church? Third, where is the monastery?

The answers to these questions are contained within a forthcoming work but the common factor which accelerated the research was the realisation that the castle was not essentially military but had a religious theme. Within a short time I became acquainted with the oral tradition that Felix, the first Bishop of East Anglia (around 630 AD) who reputedly fell from his boat in the nearby River Babingley and converted West Norfolk by founding churches at Babingley, Shernborne and Flitcham. I believe there is good archaeological evidence for Middle Saxon settlement at Babingley based upon the fieldwork conducted by Morrallee (1982) and that the vast earthworks of Rising may have begun as a non-defensive monastic enclosure possibly established by Felix himself.

There is a further connection between Felix and Rising; i.e. the recurring image of man-cats. The connection seems obvious to most; however, contrary to common belief felix in Latin means happiness, whereas the name for cat is ‘felinus or feles’. However, feles is so close to the pronunciation of Felix that it is highly likely that oral transmission has contributed to the association.

I decided to submit images which not only serve as illustrations for my broader text but also to celebrate the magnificent artistry of the Romanesque and Gothic builders.

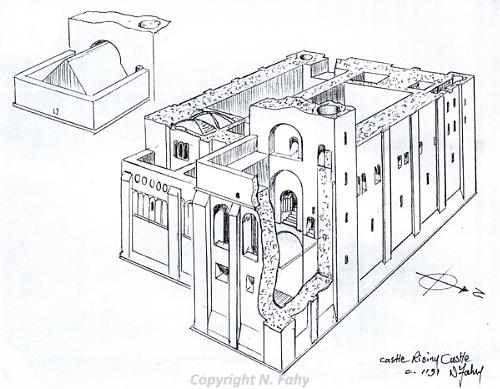

Perspective cut-away sketch of the castle keep. (© Norman Fahy.)

The main structure of Castle Rising keep shows a distinct break in construction around a level two thirds above the foundations (around 1151). This is demonstrated not only by the change but also by the quality of the workmanship and the material employed. The earlier builders appear to have belonged to a class of masons reserved for cathedrals, monasteries and churches, unlike those who followed towards the end of the 12th century who apparently lacked the skill of their forebears and were challenged by a rapidly depleting source of local sandstone known as ‘Silver Carr’ as identified by Allen (2004).

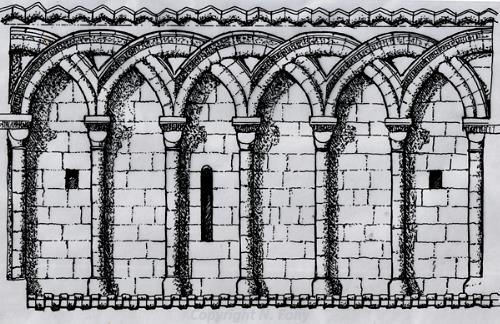

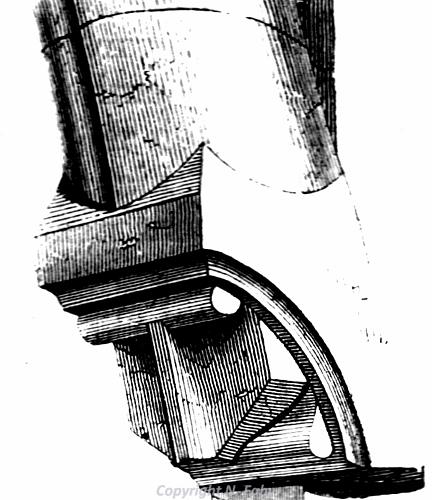

Forebuilding decoration (reconstruction). (© Norman Fahy.)

One of the most striking features of Rising Castle is the beautiful decorated frieze which adorns the forebuilding stair wall. Unlike most Norman castles, this example is lavish and replicates blind arcades more typical of cathedrals, churches, monasteries and fonts of the mid 12th century, the inference being an ecclesiastical purpose at the time of construction.

This drawing seeks to replicate the original grandeur of the Norman masonry which is best seen around mid-morning when the deep mouldings are thrown into sharp and dramatic relief. Visitors to Norwich Cathedral (NHER 226) ‘Ambulatory’ will encounter similar carved work which has been protected from the elements and still retains colour, this begs the question - was Rising Castle originally lime-washed and painted?

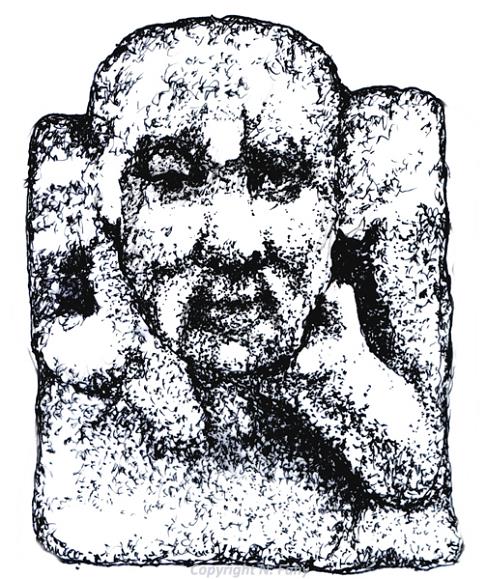

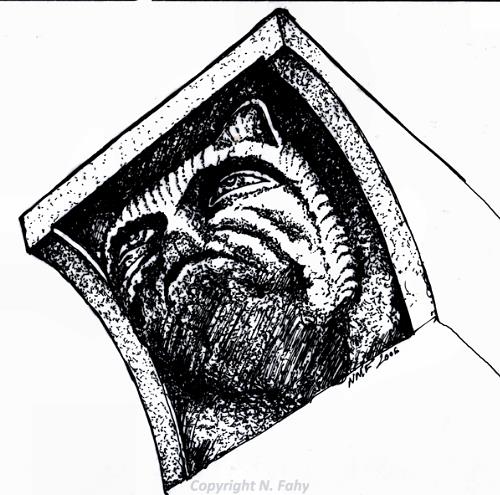

Great Hall corbel (© Norman Fahy.)

There are a series corbel stones (often wrongly referred to as gargoyles) which project from the south wall of the Great Hall with an isolated example in the north-east corner.

These decorative carvings date to the 14th century and served as stone supports for a replacement roof. The earlier Norman roof would have been a simpler affair with timber shingles, a shallow pitch and probably plain, figured corbels which were later removed leaving socket holes, some of which were clearly re-used to receive the Gothic work.

Most of the surviving 14th century corbels depict a male figure with one hand either resting the chin or possibly nursing a toothache. The other main carving over the entrance of the Ante Chapel is a ‘tongue-poker’ which represents a childish way of face pulling with the tongue truly pushed out and a common motif in churches of the period. It is unsure if these carvings were specifically designed for the castle or were selected from a mason’s yard as pre-fabricated items and simply chosen for their visual appeal.

The corbel I chose to illustrate was originally covered in grass but has recently been cleaned and conserved. This work has revealed a wealth of carved detail such as clearly defined buttons down the front of the coat and quilting on the sleeves.

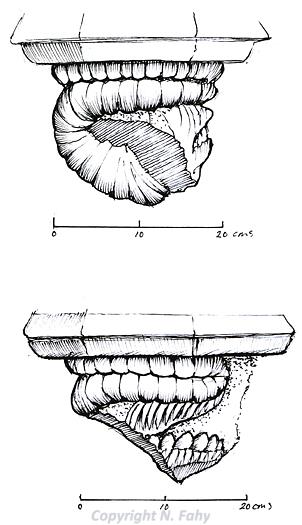

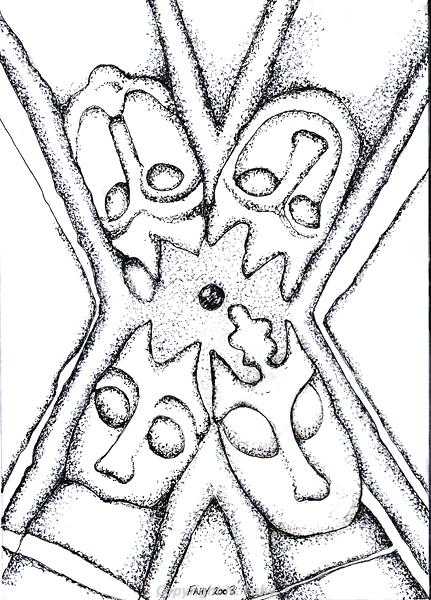

Vestibule corbel. (© Norman Fahy.)

The Vestibule boasts a collection of interesting carvings which belong to a later age than that of the original construction around 1140. The insertion of a Gothic rib-vault in the late 12th/early 13th centuries resulted in images which are both recognisable and perplexing. There are carvings of oak leaves and acorns which may refer back to the D’Albini heraldry, also an intricate knot of vine leaves which may have religious significance. The inclusion of a shellfish carving may be interpreted as a fossil ammonite which could equally reflect the maritime origins of Castle Rising or one of religious pilgrimage.

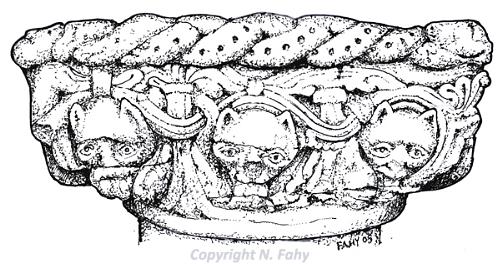

Chapel heads. (© Norman Fahy.)

The theme of cats is once again repeated within the keep chapel. Here, suspended over the chancel is a finely crafted mid 12th century quadripartite vault with naïve carvings radiating from the apex. Pevsner (1999, p.260) refers to the rib-vault boss of the chancel as decorated with ‘four faces’. Brown (1999, p.56) goes further and describes ‘four opposed crowned heads’. But closer scrutiny of these carvings reveals that three of the heads not only appear to be convincingly crowned humans, but the fourth is unmistakably that of a cat. Two of the humans have large crowns with the third human wearing a more modest coronet but with what may be an ‘oak leaf’ symbol placed centrally. The fourth head is strangely truncated below the nose with two triangular shapes on top of the head which may present cat’s ears.

There are a variety of possibilities for these images, but this writer believes they may represent the monarchs Stephen and Matilda. Having married Henry I’s widow, William D’Albini constructed his keep to honour his new bride. By the time the work reached the private chapel vault around 1150, William may have decided to make a statement in stone which pledged allegiance to his wife’s nephew, included himself (with oak leaf motif) alongside royalty, but also made reference to St Felix in his rebus form as the cat.

Intriguingly, there are carved forms of rib-vault comparable to the Rising example which have survived at the Gloucestershire church of Elkstone (Zarnecki 1951) and the exemplar of Anglo-Norman artistic expression at Kilpeck (Bailey 2000). Both examples display radiating heads but the Kilpeck vault specifically depicts cat’s heads which I feel is incidental.

The image of a man-cat has recently been exposed at Wymondham Abbey (NHER 9437), also a D’Albini foundation. This appears to be re-used material possibly from a nearby Saxon church and placed high in the east end of the north aisle. There is also the image of a man-cat amongst the array of iconic figures carved into the western façade of Castle Acre Priory church (NHER 4096).

Other more local examples of cat imagery include the 12th century font in South Wootton church (NHER 3295). Great Bircham church (NHER 1722) displays an obvious stone spout in the form of a cat’s face which has clearly been moved from the roof level to the lower bell tower. Weybourne church (NHER 6278) (Linnell et al, 1990) also has a feline label-stop on the south doorway which may be a re-used Saxon corbel stone.

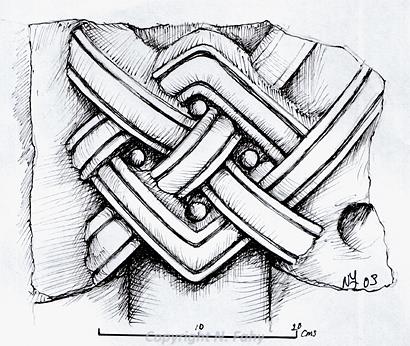

Lobby ‘Celtic’ knot. (© Norman Fahy.)

This window decoration is possibly the best in the castle and represents the Herefordshire School style previously discussed perfectly. The stone chosen for this work runs counter to the general castle construction which is locally sourced, the Lobby window and part of the north-east newel stair are carved from Caen stone specially imported from Normandy which has two fine Celtic knots fashioned into the central shaft.

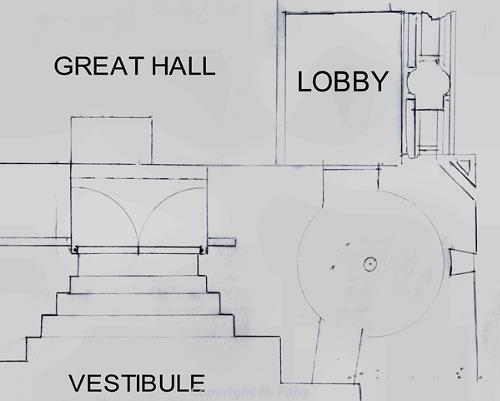

Great Hall doorway (reconstruction). (© Norman Fahy.)

The original entrance to the Great Hall was from the Vestibule, the doorway of which is decorated in a riot of Norman chevrons and ‘chip’ designs which have a distinctive ecclesiastical flavour and are also repeated on the Chancel arch of the chapel. Similar designs within Norfolk can also be found at churches such as those at Barton Bendish (NHER

4513), Haddiscoe (NHER

10702) and Heckingham (NHER

10511).

The illustration reconstructs the entrance as it would have appeared to visitors before the insertion of a Gothic rib-vault in the 14th century. This work possibly reveals miscalculations on the part of the mason which resulted not only in an asymmetry of the round-headed doorway but also the need to include a segmental arch at the centre to avoid having an inordinately narrow entrance. It appears the original design for the Vestibule incorporated a break in the wall immediately above the Great Hall entrance which may have served as a position accessed via the east mural passage for a sentry to observe visitors below. This viewing point later became the doorway to the White Room which was added to the tower in the late 12th century judging from the Romanesque windows and stone dressing marks are pre-Gothic.

Great Hall doorway plan (reconstruction). (© Norman Fahy.)

As part of the exercise to re-create the Great Hall entrance it was necessary to first establish if there had once been doors and second which direction would they have swung. The answer came from the drawing and illustrates how a pair of doors could have been draw-bolted and when opened arc into a space provided in the castle wall. Further to this, it is apparent that a series of timber steps were required to elevate a visitor from the Vestibule to the level of the Great Hall. This plan also incorporates useful detail of the Lobby which is discussed below.

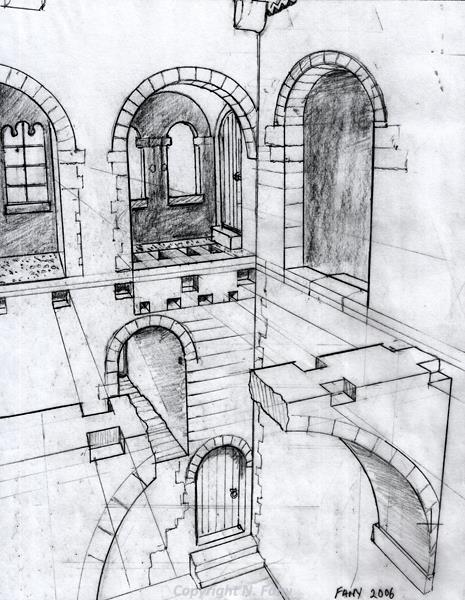

Perspective sketch of the Lobby (reconstruction). (© Norman Fahy.)

The function of the ‘Lobby’ has been debated for decades, but this writer controversially suggests that the area may have originally been designed for the purpose of singing.

Brown (1999, p.50) describes the Lobby as; ‘a small groined entrance lobby in the thickness of the north wall and formed out of the first window opening’. At present, visitors simply pass through this area without any knowledge of its original importance.

For most people, like Bradfer-Lawrence (1932 p.37) the lobby is simply a part of the mural passage thrust through the north wall arcade during the 16th century. However, there are a few clues as to the original function of this area provided by three 19th century commentators. First, Harrod’s work (1857, p.56-7) includes a plan illustrating the first floor of the castle and designates the lobby as ‘F’. This image clearly shows a complex segmental arrangement of masonry which may or may not have projected into the basement level of the castle.

Second, Taylor (1850, p.22-3) provides not only a plan but also a written description of the area which concurs with Harrod’s analysis:

‘The window at the east end, (E) which is of two lights, is worthy of careful examination, being rich in ornamental detail. Near to this is a curious arrangement, consisting of three [sic] openings, by which for some purpose a connexion was made between the ground floor and the first storey; the express intention of them will afford matters for conjecture, but it may readily be conceived that in the case of siege, when even internal communication might be cut-off the means of conveying provisions or even information from one apartment to another, might be turned to a considerable advantage’.

Taylor appears to be convinced that the lost structure once represented communication shafts which he actually illustrates with four openings on his plan and not three. In partial support of Taylor’s siege theory it must be observed that the door which originally secured the Great Hall basement from its counterpart space to the south was draw-bolted on the Great hall side. Third, Clark (1884, p.370):

‘Four of these bays open by large arches, at the floor-level, into the great chamber, of which this gallery thus formed a part. The eastern bay communicates with the well-stair. It is groined, and its side towards the chamber seems to have been partially closed, and there are three small shafts which seem to have opened into the mural chamber below. They cannot be for garderobes, and their use is obscure. This bay has a very handsome window, of two lights, coupled, and the shaft common to the two is worked in a rather remarkable fret or knot. These windows had shutters. There is no trace of glass.’

Again, as with Taylor ‘three’ shafts are described in the written record and yet four are depicted on his first floor plan.

The lobby occupies the first of four large window arches which form the north wall of the Great Hall. The two-light lobby window is constructed from Normandy ‘Caen’ stone and incorporates two elegant carved Celtic knot designs either side of the central shaft. Unfortunately, the frame is both weather-worn and crudely re-constructed with brick on its western extremity. The fine rendered groin vault remains intact and despite the ancient deposit of grime may still carry evidence of colour.

Originally, access to this chamber may have been exclusively from the northeast newel stair having once opened a right-hinged door. There is evidence within the masonry of the lobby arch which may suggest that the area would have been completely separated from the Great Hall by a wainscot screen which could have included an alternate access door or hatch. Collectively, these factors suggest something of much greater importance than previously considered by other observers; the result of this recent research may reveal something of greater and profound significance.

There is faint but positive evidence that the walls of the Great Hall basement once exhibited a rendered surface which suggests that area was not originally confined to the basic function of storage. The theory presented here is that the basement of Castle Rising was much more than a storage room and may have once served as an area of congregation. This has since prompted the consideration of variations explanations for the lobby structure, one of which surprisingly includes the conveyance of sound.

Friar (1996, p.12) refers to various systems of amplification used by medieval monasteries;

'In many monastic churches acoustic chambers were intended to provide extra resonance and amplification during the singing of plainsong and to make 'hauteyn speche ring out as round as gooth a belle'. Those at Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire consisted simply of rows of ceramic jars laid on their sides, but elsewhere sophisticated drain-like series of boxes were constructed beneath choir stalls for the same purpose'.

This description certainly carries some similarity to what once existed at Rising and prompts an array of thoughts as to the original function. The consideration here is that the Great Hall basement may have once served as a meeting point for the entourage of the castle during religious calendar dates and that the ‘sound holes’ provided an ethereal addition to proceedings.

Notch-heads. (© Norman Fahy.)

The southwest tower of the castle has caused much debate amongst architectural historians and archaeologists alike as it not only contains Norman columns and capitals but is also juxtaposed by an early Gothic lancet window which must be late 12th century in construction and huge ‘notch-heads’ which could reasonably date from the early 13th to the early 14th centuries.

Keen eyed visitors to the castle may have noticed two curious carvings nestling near the top of the southwest tower. These carvings look like two frowning, beak nosed masks and repeat a medieval motif form known as notch-heads which Parker (1905, p.155) describes as;

‘a kind of corbel, the shadow of which bears a close resemblance to that of a human face; it is common in some districts in work of the 13th and 14th centuries and is usually carved under the eaves as a corbel table’.

The notch-head designs clearly belong to substantial lengths of masonry which suggests they were intended to be embedded deeply within a wall and designed to support a great weight, i.e. roof timbers. If this is correct, they were intended for the interior of the castle or another structure but were never used. Notch-heads were frequently used as label-stops for church windows and doorways of the period and vary in design from region to region; good Norfolk examples can be seen both at Flitcham (NHER 3484) and Grimston (NHER 3608) parish churches; also, the Fenland church of St Mary West Walton (NHER 2210) demonstrates Parker’s description of eave decoration which dates to between 1225 and 1240 (Mortlock and Roberts 1985, Vol.3, p.158).

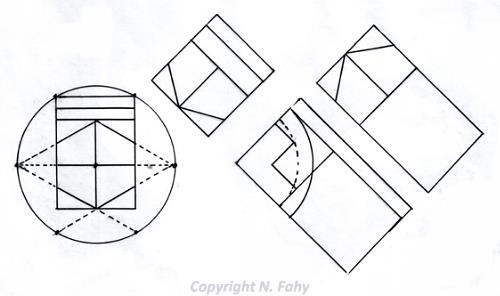

Geometric analysis of notch-heads. (© Norman Fahy.)

I decided to investigate how a medieval mason would have designed such a carving and was surprised at the complexity of the work. I actually had to resort making a modelling clay miniature to appreciate the geometric construction involved to produce a projection drawing. This revealed that the whole design is based upon a hexagon and achievable using a compass and square, both stock instruments used by stone masons since ancient times.

Notch-head after Parker. (© Norman Fahy.)

The font. (© Norman Fahy.)

This can be found in the nave of St Lawrence (NHER

3309) in Castle Rising and originally belonged to the 11th century church associated with the castle (Harrod 1857, p.50) (Taylor 1850, p.7). Curiously, the font is only decorated on two sides which suggests that it was originally designed to stand in a corner; however the plinth was found directly between the north and south doors. The local historian David Grimes claims that the traditional location for fonts in Norfolk was the northwest corner of the nave or next to the north door.

The three carved heads are frequently mistaken for horned devils, but on closer inspection they appear to be anthropomorphic cats with beards and expressions. One explanation may be that they represent the Holy Trinity in some curious way. Pevsner (2000, p.254) tentatively refers to the heads as cats, whereas Mortlock and Roberts (1985, Vol.3, p.23) simply regard them as ‘animal masks’.

Pounds (1995, p.15) reminds us that when early fonts were being carved there remained elements of pagan belief among ordinary people and that some of the symbols are difficult to reconcile. The author cites forms found in the West Country consisting of square topped bowls, central pillars and four corner shafts which include images of reptiles and cat-like creatures together with ‘rope-like moldings worked into knots and patterns’; this is a fair description of the St Lawrence font apart from the fact that the Norfolk example is supported by a single pillar and is therefore an early 12th century form. The decoration on the Rising font is of a distinctly ‘Celtic’ design and reminiscent of the Herefordshire School of sculpture which existed precisely when Rising keep was being erected (Thurlby 2002). There is further evidence of the Herefordshire School within the fabric of the castle; for instance those stone heads which project from the roundels of the fore-building stair, the carved string-course figures of the tower and the elegant Celtic knots attached to the mural passage window – all belong to the Herefordshire tradition.

Reedham Cat. (© Norman Fahy.)

Following the theme of cats and attempting to link St Felix with that image, I was led to those locations which recorded Felix’ progress from Dommoc (Dunwich), the newly appointed Bishop of East Anglia appears to have established two Norfolk churches, one at Loddon (NHER

10538) and another at Reedham (NHER

10419) near to the Suffolk border (Williamson 1997, p.144); (Farmer 1988, p.157) before sailing round the Norfolk coast until he encountered The Wash. Early sources for this account include; William of Malmesbury, Liber Eliensis (Ely) and Liber Albus (Bury St Edmunds).

Whilst Loddon church appears to have no archaeological remains dating to the 7th century, Reedham church is a spectacular example of recycled older material. The detailed analysis presented by Allen (2004) explains how Leziate quartzite; i.e. the main stock material of which Castle Rising is constructed, came to be an integral part of the east Norfolk 13th century structure. Apparently, Roman builders recognized the value of ‘Silver Carr’ stone and employed its use in the construction of Brancaster Fort (NHER 1001); further to this they appear to have shipped the material via the river Babingley, around the north coast then navigated the River Yare to deliver sound building stone for the construction of a lighthouse at Reedham. A quick examination of Reedham church reveals a fascinating amalgam of material comprising of Roman brick, tile and Silver Carr stone sourced from Sandringham. The re-constructive illustration of the Reedham cat reveals that the masonry may once have served as an internal corbel or roof support.

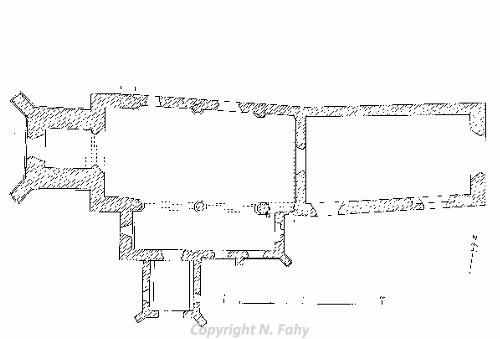

Babingley church plan 1 (after Batcock). (© Norman Fahy.)

In an effort to expand my knowledge of the St Felix story I chose to examine the ruined church dedicated to that saint at Babingley (NHER

3257). I feel Morrallee (1982) has already established early 7th century occupation on this site via field walking thus implying Felix managed to attract a community of converts. Unfortunately, the site chosen for an initial chapel must have been prone to flooding during Spring tides etc. What transpired may be that Felix’ community re-located to the area presently occupied by Castle Rising and its earthworks.

Batcock (1991) interprets a sequence of construction from the standing fabric and divides it into three distinct phases; ‘The first consists of the arcade and aisles, added to a pre-existing nave whose west wall probably aligned with the west walls of the aisles; this phase makes use of much Sandringham stone, and is poorly coursed. Secondly, the chancel was added to the nave; the masonry here is similar to the nave, but uses more carstone higher up. The third phase involved the extension of the nave to west and the addition of the west tower; there is still scarring where the original west wall was pulled down. Carstone is greatly used, particularly in the lower part of the tower’.]

The process of medieval church construction normally began with the chancel followed by the development of the nave, aisle, side-chapels and bell-tower from secular funds. Batcock perceived the distribution of Sandringham stone (Silver Carr) within the construction of Babingley church but may have been unaware that the resource became scarce towards the end of the 12th century and the reason for the material appearing at higher levels of construction may be due to re-cycling of Norman stonework in the 14th century.

My interest was primarily drawn to the ground-plan which demonstrates a difference in alignment between the chancel and the rest of the building. This arrangement is referred to as a ‘weeping’ chancel by Cautley (1949) and suggests an early foundation of which the chancel which may have been laid-out with a poor method of determining the magnetic cardinal points.

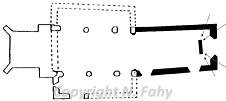

Babingley church plan 2 (after Batcock). (© Norman Fahy.)

Further to an interest in the building sequence of Babingley church I followed a line of enquiry regarding a series of square holes radiating from the chancel. There had once been four but one had been sealed at some point in time. The insertion of surveying poles through those that remained revealed something really interesting; each hole provided a clear view or squint of the high altar from outside.

Squints or hagioscopes once provided views of the high altars in many medieval churches. However, this was to allow celebrants in side chapels to synchronise their rituals with those of the chancel. The squints at Babingley clearly do not follow this arrangement and it would have been unheard of for parishioners to view the act of Eucharist from outside.

One possible explanation for these squints may lie in the work of R.J. Brown (1998, p122) which includes a fascinating reference to ‘Anchorite or Hermit Cells’ within his study of English village churches;

‘Anchorites and anchoresses were people who sought to live solitary and pious lives, and they were almost regarded as saints by the common people. They were inducted to their cell by the Bishop in ritual procession. This cell usually took the form of a lean-to annex built on to the cold, north wall of the sanctuary of the church. Here they would spend the remainder of their lives, for once they were inside, the entrance was permanently blocked up. Their only contact with the outside world was through a small opening in the inside wall, giving a permanent view of the High Altar, so that the occupant could observe the priest celebrating mass – and a small barred and shuttered window in the outer wall that admitted some light and enabled food and drink to be passed to the occupant’.

The presence of hermit cells attached to a 14th century church is rare and more typical of the Saxon period. This may imply that Babingley survived as a pilgrimage destination well into the medieval period

Watkin (1948) presents a detailed record of the contents of St Felix’ church ‘Babbynglee’ during the reign of Edward III (1327 to 1377) and reveals a wealth of possessions held by Bartholemew the Rector which included a gold chalice and valuable music books. The church was valued together with that of nearby Wolferton at 13½ marks.

Blomfield & Parkin (1805-10, Vol. VIII, p.347) reflect upon the medieval heraldry once displayed within Babingley church; ‘In the church were arms, Sable, a cross ingrailed, Or, Ufford Earl of Suffolk; Sable, three standing cup, covered argent, Boteler or Butler, Gules, a Chevron, Or’. The display of such arms suggests the activity of wealthy medieval benefactors donating funds to a church which could be regarded as both remote and otherwise insignificant. Further to this, the Will of John Cobbe (see Fuller) dated Babingley 25th March 1486 clearly bequeaths 20 pence to provide a guild light of St Felix suggesting an enduring cult centre long after the Black Death. The fate of the medieval chancel screen from this church is recounted by Herbert-Jones (1883, pp. 310-11).

APPENDIX A.

The screen in Babingley Church, when the church was "put into repair" in 1850, was already in fragments, and the panels containing the figures were lying, broken and disfigured, in a pile of rubbish. In 1854 they had entirely disappeared, and had been, according to the statement of the clerk, broken up for firewood. Some watercolour drawings were made of eighteen of the panels just before their destruction; these are to be found in Vol. I of the "Additional Illustrations" to Mr Dawson Turner's copy of the "History of Norfolk," by Blomefield, now in the British Museum. The figures in these coloured copies are reduced to about six inches, and are painted with the finish and lustre of early illuminated work.

The following suggestions as to the identity of the figures are founded in part on the description of the saints and their emblems given by Dr. Husenbeth, and, in most of the instances, on the observations of Mr G. Gilbert Scott, to whom the subject has been referred…...

Figure iii. On a gold and red background, dressed in green and scarlet robes, of the form commonly appropriated to an apostle or evangelist, - a man's figure with a staff and book, and an animal at his feet which is like a stoat or weasel.’

Of the twelve saints depicted on the screen, only one seems to have eluded identification by both Husenbeth and Gilbert Scott. However, the figure of a saint dressed in apostle’s robes carrying a staff and book with mammals at his feet really must be a representation of St Felix and a demonstration of the survival of his cult at Babingley into the medieval period.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, J.R.L., 2004. Carrstone in Norfolk Buildings: Distribution, use, associates and influences. BAR 371. Banbury.

Bailey, J., 2000. The parish church of St Mary & St David at Kilpeck. Four Seasons Press. Hereford.

Batcock, N.,1991. The ruined and disused churches of Norfolk. East Anglian Arch. 51. p88

Blomefield, F., 1805-10. An Essay towards a topographical history of the county of Norfolk IX continued by C. Parkin, (London, 2nd edition), note - Babingley, Vol VIII. p 351, Flitcham, Vol VIII. p 410, Shernbourne Vol X. p 350.

Bradfer-Lawrence. H. L., 1929. Castle Rising – A short history and description of the castle. King’s Lynn.

Brown, R. A.,1999. Rising Castle Castle. English Heritage. London.

Brown, R.J.,1998., The English Village Church. Robert Hale. London.

Cautley, H.M., 1949. Norfolk Churches. Alard & Co. Ltd. Ipswich.

Clark, G.T., 1884. Mediæval Military Architecture in England. Vol 1. Wyman. London.

Farmer, D.H., 1988. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford University Press.

Friar, S., 1996. A Companion to the English Parish Church. Bramley Books. Surrey.

Harrod, H., 1857. ‘Castle Rising’. Gleanings among the Castles and Convents of Norfolk. Norwich. 25-70.

Herbert-Jones, 1883. Sandringham Past & Present. Sampson Low & Co.. London.

Linnell, C.L.S. et al, 1990. Weybourne Priory and Parish Church. North Walsham. Norfolk.

Mortlock, D. P. & Roberts, C. V., 1981. The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches. Vol. 1. North-East Norfolk.

Mortlock, D. P. & Roberts, C. V., 1985. The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches. Vol. 2. Norwich Central and South Norfolk.

Mortlock, D. P. & Roberts, C. V., 1985. The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches. Vol. 3. West and South-West Norfolk. Acorn Editions. Cambridge.

Pevsner, N., & Wilson, B., 2000. Buildings of England. Norfolk 1 & 2: North-West and South. Penguin Books. London.

Pounds, N., 1995. Church Fonts. Shire Album 318. Shire Publications. Princes Risborough.

Taylor, W., 1850. The History and Antiquities of Castle Rising, Norfolk. Kings Lynn.

Thurlby, M., 2002. The Herefordshire School of Romanesque Sculpture. Logaston Press. Herefordshire.

Watkin, A., 1948. Archdeconry of Norwich; Inventory of Church Goods temp Edward III. Norfolk Record Society. Vol. XIX. Part II.

Williamson, T., 1997. The Origins of Norfolk. Manchester University Press.

Zarnecki, G., 1951. English Romanesque Sculpture 1066-1140. London

PERIODICALS

Morrallee, J., 1982. ‘Babingley and the birth of Christianity in East Anglia’, NAHRG News, 31, 7 – 11.

OTHER SOURCES:

Fuller n.d. ‘The Will of John Cobb 1486’. Norwich Archdeaconry Register. 98