The word ‘villa’ is Latin in origin and refers to a kind of agricultural establishment where people lived and farmed, although this term could also be used to refer to more luxurious accommodation. However, there is a degree of controversy over what a villa actually was, as archaeological evidence for these sites varies so much. Safe to say, a villa could denote a single principal dwelling, or a group of buildings inhabited by a landowner of some prestige, his family, and estate workers.

They usually have a rectangular floor plan and use stone, solid floors and often have adjoining bath houses for use by the owner and his family.

Feltwell Little Oulsham Drove villa and bath house (NHER 5205)

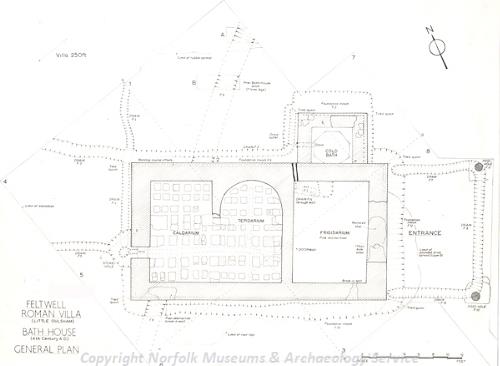

The Feltwell villa came to light in 1960 after ploughing uncovered tiles, pink mortar and large flints commonly used for such buildings. Later excavations uncovered what turned out to be an adjoining, internal, bath house, and although the brick and tile remains were in poor condition it was still possible to see evidence of a caldarium with a furnace in the northwest end, tepidarium, and frigidarium with an octagonal cold bath on the northeast side.

A plan of the Roman villa and bath house excavated in Feltwell in the 1960s. (© NCC)

An iron sword with scabbard of Early Saxon origin was found in situ in the hypocaust of the villa in 1961. It seems that the sword had been placed under concealment in the hypocaust when part of the tiled floor had been moved. Although X-rays reveal it is not of a remarkably high quality of craftsmanship, it is nevertheless believed to be the earliest of its type to have survived in Britain. Peculiarly, the antler grip of the sword has survived in good condition, though the wooden hand guards on and around the grip have decayed and the pommel is missing. The pommel is likely to have been boat-shaped, a staple feature of swords of that particular era.

It is unlikely that the Feltwell sword was made in England. Archaeologists suppose it was brought over with the first Anglian settlers or maybe raiders. Its presence does not, however, automatically imply that there was any specific form of long-term reoccupation of the site. It is more likely that in those troubled years following the decline of secure Roman presence, such a treasured item would have been buried more for safety’s sake than anything else.

A large bronze brooch, a necklace fastener, glass beads, a coin and various sherds of pottery dated around the fourth century have also been found around the site. Finds associated with the Roman villa itself include a steelyard and two objects of elephant ivory. A few hundred feet southwest of the bath house lies a large mound containing the foundations of a Romano-British house or farm.

The villa itself is thought to have been small and simple, lacking in frivolous mosaic or tessellated floors, with plain plastered walls and wooden floors more the style. As for the bath house, it is unlikely it would have been constructed with the intention of providing the owner a place of leisure or luxury, it was more likely to be something of an estate amenity, posing the possibility of it being used by estate workers as well as the owner of the villa and his family.

There is no evidence to suggest the villa remained in use after it’s Roman occupation in the fourth century, although finds around the site point to the possibility of later settlers in the region, probably due to the rich agricultural potential of the area.

Feltwell Glebe Farm bath house (NHER 4921)

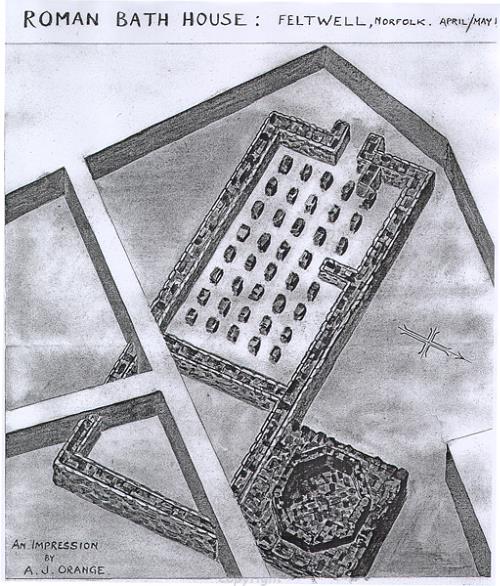

The bath house at Feltwell Glebe Farm was excavated in 1962, after the discovery of Roman building material and pottery sherds on the site. Further digs concluded that the bath house had been badly robbed, but despite this the perimeters of the building were still apparent, with hot and cold baths and a frigidarium, the floors of which had been robbed of their tiles. All the masonry from the bath rooms had also been robbed.

A watercolour receonstruction of Feltwell Roman bath house. (© NCC)

It is believed that this site was in use for a considerable amount of time, this is becuase large quantities of ash and soot were found around the stokehole, in the west end.

Finds from the site include the usual array of pottery vital to the dating process, a lead ball with iron ring, small fragments of lead and iron, nails, and a coin of Tetreus. A key possibly belonging to the building was also found in the area. The well itself yielded an abundance of bones, broken tiles and flints. The heads of five oxen were found in a well in the hot room. These bones has not been butchered for food and may have been ritually sacrificed.

Grimston villa (NHER 3575)

Photograph of excavations at Grimston villa in 1906.

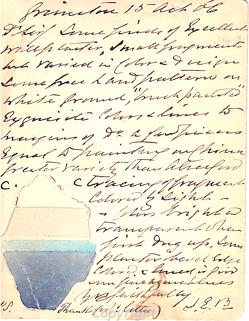

The Roman villa at Grimston was discovered in 1860, but excavations didn't begin until 45 years later in 1905. It is a tripartite winged corridor villa, the finds including painted plaster, tesserae, Samian sherds, lead objects, bone and of course pottery. Two rectangular objects of fired clay with a central hole were also found.

A postcard written by J.E.B. in 1906 describing the discovery of painted wall plaster at Grimston villa.

Much of the material was removed from the Grimston site before it was properly identified as a place of archaeological significance, even to the extent of tiles from the site being reused in farm buildings.

Gayton Thorpe villa (NHER 3743)

Discovered in 1906, the two blocked winged corridor villa at Gayton Thorpe has yielded an abundance of finds, despite having been badly damaged by ploughing pre-excavation. Whilst Roman sherds, building materials and pottery are typical of the area there are also a number of artefacts dating from the Iron Age, Early Saxon and medieval eras. One fascinating find in particular is that of a Roman tile-stamp bearing the emblem of the Sixth Legion – something very uncommon in the Norfolk area, as the sixth legion are normally associated with the Hadrianic period of the Roman occupation of Britain.

The main excavation of the villa began in 1922 when it was believed that the building might have been the summer residence of a Gaulish official. Finds included three coins, a set of bronze toilet implements, a brooch, a bracelet, bones, a glass jar and an iron knife.

Evidence suggests that the whole villa was roofed with tiles, and a hypocaust was also found in one of the rooms. Tesserae used to create mosaics were uncovered in red, white and blue, and there were additional fragments of small bluish semi-transparent glass found in a large mosaic in one of the rooms. The toilet implements found on the site are intriguing because they look similar to modern equivalents. Among them were an earpick, tweezers and a nail-cleaner. Such sets are not uncommon in other Roman sites, and an almost identical set can be seen in the Guildhall Museum in London.

A fieldwalking survey in the 1980s concluded that there may well have been a number of other buildings located in the vicinity of the villa, amongst them a detached bath-house with a tessellated floor. A spring located nearby suggests why this estate set-up may have developed: the water supply would have been a prime attraction for the builders of the villa, and a considerable advantage to settlements nearby. The site was most recently investigated in 2006. Geophysical survey located the bath house and other features in the surrounding landscape. The mosaic was re-excavated although it was found to be in fairly fragmentary and eroded condition.

The villa was occupied by around 150 AD, and the presence of coins, pottery and other articles suggests that this occupation lasted until around 300 AD.

Methwold (NHER 4780)

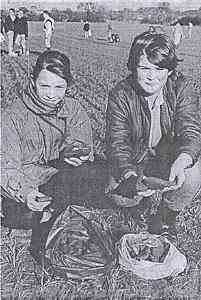

Methwold is home to a Roman villa with a hypocaust (a furnace that heats rooms through narrow gaps in the walls), first excavated in 1887, then left until rediscovered in 1932. Three small rooms were found, one warmed by the hypocaust, and all showing the presence of tiles on the floor. From 1990-1994 finds such as floor tiles, roof tiles, oyster shells and box tiles were found on site, and there were also fragments of opus signinum.

Methwold High School students fieldwalking on the site of Methwold Roman villa. (© Eastern Daily Press.)

Amongst the finds uncovered on site were seven Roman coins, a dolphin brooch, a votive bronze axe and a decorative bronze mount depicting a lion’s head.

There are a number of Roman masonry buildings located along the Norfolk fen edge, and the Methwold villa is one of these. It may have represented the centre of a Roman estate, a principal dwelling with other buildings surrounding it. It is also believed that the fen edge might have been home to a Roman temple as well, probably as a result of the numerous settlements in the vicinity.

Nic Zuppardi (Notre Dame High School, Norwich), September 2005.