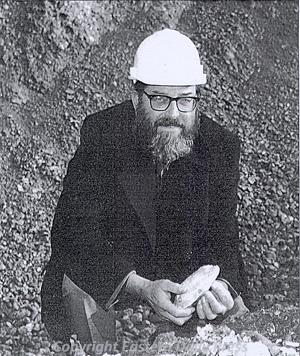

John Wymer, 1928 to 2006. (© Eastern Daily Press.)

A unique practitioner and scholar has been lost to East Anglian, British and world archaeology. From the moment on the 30 July 1955 when he discovered a third part of a human skull at a gravel pit at Swanscombe to the publication of the discoveries at Pakefield in the 15 December 2005 edition of Nature John Wymer led an enormously productive archaeological life. We in East Anglia have had the privilege of his company for many years. He served as President of the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society from 1990 to 1992 and was elected President of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History in 2001. He was also an active member of the Scole Committee and of the CBA East Anglia.

Having discharged his National Service commitments in the RAF Wymer began work as a teacher at Wokingham in 1956. After a short while he was appointed archaeologist at Reading Museum. As well as conducting major excavations such as of the Mesolithic site at Thatcham and of the long barrow at Lambourn, he found time to create a masterful display of Roman material from Silchester. For four years between 1965 and 1969 he worked in South Africa with Professor Ronald Singer of the University of Chicago. Their work culminated in the excavation of the deeply stratified Palaeolithic sequence at Klasies River Mouth, a site of enormous significance for the prehistory of South Africa where the world’s earliest bones of Homo sapiens sapiens were recovered. Things became too difficult in South Africa but the Singer/Wymer collaboration continued in England, first with the Palaeolithic site at Clacton in 1969-70. A field trip to Iran was followed by five seasons at Hoxne, where the discovery of hand-axes in 1797, had prompted another John, Frere of Roydon Hall, to suggest the very great antiquity of Man.

After funding problems had brought an end to major Palaeolithic field projects Wymer served two years during 1979 and 1980 as a Research Associate in the Environmental Sciences Department of UEA. This sojourn gave him time to write some important works which were to see publication in the 1980s. His surroundings were to change utterly and he spent most of 1981 in south-east Essex on a 7-hectare multi-period site at North Shoebury. Again funds ran short: what was supposed to be a much longer project ceased after one year. In 1983 he was appointed a Field Officer with the Norfolk Archaeological Unit with which he spent seven very productive years, excavating an early Mesolithic site at Banham, several barrows, at Bawsey, Longham, Lyng and Southacre, the latter with its Anglo-Saxon execution cemetery, and recording Late Palaeolithic flints in-situ within peat below the low water mark at Titchwell.

The 1990s saw what might be described as “the climax of the Wymerian”, comprising the Southern Rivers Palaeolithic Project, the English Rivers Palaeolithic Survey and the Welsh Lower Palaeolithic Project. Working with Wessex Archaeology Wymer surveyed and topographically assessed every known Palaeolithic site in England and Wales and the seven published volumes will remain the sine qua non of research projects and curatorial decisions for many years to come.

Throughout his career Wymer made sure that his archaeological activities were promptly and lucidly reported. As well as papers concerning individual sites he was also adept at the collection, ordering and synthesis of disparate data. This rare skill can be seen in his Lower Palaeolithic Archaeology in Britain as Represented by the Thames Valley (1968), Gazetteer of Mesolithic Sites in England and Wales (1977), The Palaeolithic Age (1982), and Palaeolithic Sites in East Anglia (1985). His bibliography runs to more than 120 publications. Along with a crisp and clean writing style came a great ability as a draughtsman. This was most apparent in his treatment of flint artefacts. Knowing, as an accomplished knapper, by which means an object had arrived at its final form, he was able to produce wonderful drawings, uncluttered, simple and informative. His lectures were a joy to attend. Whether addressing an international symposium or an evening class, he transmitted his ideas with precision, accuracy and unfailingly with humour. His ability to explain without condescension the complexities of the Pleistocene to the layman was outstanding. Indeed his modesty shone through even when he was in full flow on a chosen subject. A talk on Palaeolithic cave art given to a group of inmates at Wayland Prison was a source of lasting inspiration for many of them.

John Wymer was no narrow-minded specialist and far from a constant talker of shop. Just as Pleistocene studies necessitate a wide range of interdisciplinary cooperation, so were his interests eclectic. Amongst his many loves were steam railways, the writings of A.E. Housman, Saki and Anthony Powell, the piano music of Jimmy Yancey and Cripple Clarence Lofton, the singing of Bessie Smith, the wit of Groucho Marx, fine ale, mussels and, above all, life. As a bon viveur, boogie pianist and companion he will be missed by many both within and outside the archaeological community. As an archaeologist and prehistorian he will not be forgotten.

Andrew Rogerson (NLA).

Published as:

Rogerson, A., 2006. 'John James Wymer MA, Hon DSc, FSA, FBA, MIFA', CBA East Anglia Region Newsletter. Issue 3.