We go a long way back into the depths of time this month to the Old Stone Age in the so-called Palaeolithic period. This period spans the time from around 800,000-10,000 BC. The find for this month is an early or lower Palaeolithic ovate Hand Axe that unusually was found on the surface of a ploughed field near Wymondham.

The axe was made in antiquity by roughing-out the shape from a flint nodule with a hard hammer stone such as quartzite. This initial stage would then be followed by carefully working the edges of the flint from both faces with a soft hammer such as antler or a softer variety of stone like sandstone. The purpose of the finished tool would be have been primarily for the butchery of meat.

Photographic image of the Palaeolithic flint Hand Axe

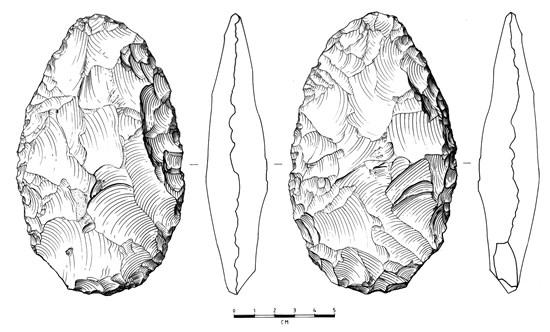

A hand-drawn illustration of the same Hand Axe

In archaeological recording it is common to hand-draw flint tools. The two graphics above illustrate why this is the case. The top photographic image gives a good idea of shape and surface colouration, but because of lighting constraints and limitations regarding depth of focus, it does little to help researchers understand how the flint was made. However, the illustration (the lower image) drawn by our Historic Environment Services illustrator Jason Gibbons, not only reproduces complete accuracy, but allows the flint to be studied in detail under a whole range of lighting conditions. This photographically-unseen information can then be interpreted and faithfully recorded on the drawing. The so-called ripples that are often featured on the surface of a struck flake are like ripples on the surface of a pond, in that they lead back concentrically to their origin. On the drawing therefore the ripples shown on each struck facet lead back to a point of striking, revealing much more than a simple photograph could ever do about how the axe was made.

The expert drawing gives fitting testament to the fantastic skill of the prehistoric craftsman who carefully fashioned the tool, and evidences his intimate understanding of the material he was using and the techniques required to manipulate it circa 400,000 years ago.

The full record of this Palaeolithic Hand Axe can be viewed on the Portable Antiquities database website on www.finds.org.uk and is record reference NMS-C94303.