This Parish Summary is an overview of the large amount of information held for the parish, and only selected examples of sites and finds in each period are given. It has been beyond the scope of the project to carry out detailed research into the historical background, documents, maps or other sources, but we hope that the Parish Summaries will encourage users to refer to the detailed records, and to consult the bibliographical sources referred to below. Feedback and any corrections are welcomed by email to heritage@norfolk.gov.uk

The parish of Shouldham is located to the west of Norfolk, within the Nar Valley. It lies to the east of Marham, south of Wormegay and north of Fincham. The village itself lies in the lee of a chalk ridge that rises above the fens and the valley floor. Mere plot is the only area of deep peat that remains and it lies to the west of the conifer-clad sandhill known as Shouldham Common; a dominant feature within the landscape. The name Shouldham derives from the Old English meaning ‘homestead that paid rent’. The parish has a long history and was certainly well established by the time of the Norman Conquest, its population, land ownership and productive resources being extensively detailed in the Domesday Book of 1086. This document reveals that before 1066 the lands were under the jurisdiction of Thorkell and that after the conquest Ralph Baynard held the lands here. The parish had plentiful agricultural resources including numerous sheep as well as beehives, a mill and a fishery. Shouldham's two churches were also mentioned in this document.

The fenland resources of Shouldham mean that the parish was occupied from as early as the Mesolithic period of prehistory. Virtually every field on the southern slopes on the valley has produced worked Mesolithic (NHER 36175) and Neolithic flints as well as pot boilers scatters (e.g. NHER 23282 and 24081). Five of these flint tools take the form of axeheads (NHER 15810 and 15811) but other tools like scrapers have also been found. It is also worth noting that an intriguing flint 'anvil stone' of prehistoric date has been found at the highest point of Shouldham Warren (NHER 17287).

Fieldwalking has discovered two sites of particular interest amongst the numerous and widely distributed flint scatters. The first of these is located near to Shouldham Warren and constitutes a Mesolithic site protected by the peat. This location was reused later during the Neolithic period for flint working, probably on a seasonal basis (NHER 23283). The other site is situated atop a ridge in the valley (NHER 24082) and had several distinct pot boiler scatters.

Aerial photographs of Shouldham reveal a number of enclosures which were visible as cropmarks. Several of these took the form of ring ditches (NHER 16150, 16151) and it is possible that these indicate activity in the parish during the Bronze Age. Indeed, the one near to Marham airfield (NHER 24296) seems a very plausible Bronze Age feature. When combined with the discovery of Bronze Age cremation urns in the area of the medieval priory (NHER 4255) the evidence may suggest some low-level occupation during this period. Other finds dating to the Bronze Age have been retrieved from the parish and comprise a bronze blade from an unidentified tool (NHER 34390) and a set of worked flints including a scraper (NHER 18541).

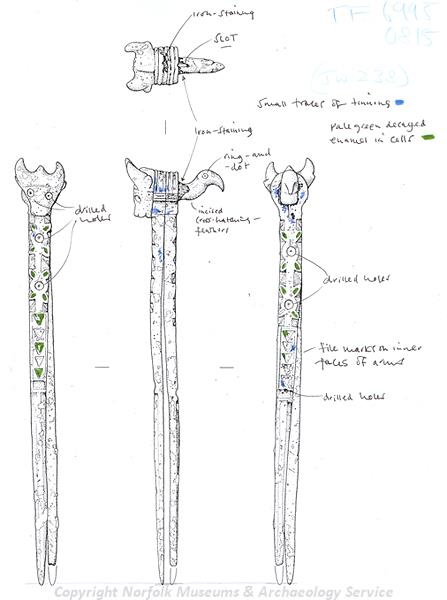

The anthropoid handle of an Iron Age sword. (© NCC)

The most important Iron Age find from Shouldham was discovered in 1944. Digging for gravel in a field uncovered an inhumation burial with an anthropoid sword (NHER

4256). This sort of sword is particularly rare and the sword from Shouldham has been recognised as one of international importance. Additionally, cropmarks visible on aerial photographs taken over fields to the northeast of Shouldham village show two potential Iron Age roundhouses (NHER

24083). Metal detecting has also found seven Iron Age coins including several silver coins (NHER

35714,

31797) minted by the Iceni tribe and objects such as terrets (NHER

34388).

A remarkable pair of Roman dividers. (© NCC)

Shouldham appears to have been a centre of some importance during the Roman period. A large settlement (NHER

28645) existed during this time and a huge array of finds relating to domestic life, manufacturing, religion and ornamentation have been recovered from the occupation area. Over 700 coins have been found here and their distribution may suggest some sort of ritual centre, a notion supported by the discovery of a votive staff on site and a votive palstave (NHER

39658) elsewhere in the parish. However, it is also possible that the sheer number of metalwork objects that this site was engaged in some sort of manufacturing and was thus an industrial centre. Perhaps this latter suggestion is more plausible as several pottery kiln sites (NHER

4252) and an ironworking site (NHER

4282) have been recorded in the surrounding landscape. A number of fine Roman artefacts have also been found at various locations in Shouldham by metal detecting. A bracelet was found in Church Lane (NHER

23322), a pendant in Gallow Lane (NHER

18199) a seal box northwest of Mill Farm (NHER

37136) and a brooch (NHER

21350) on Shouldham Warren.

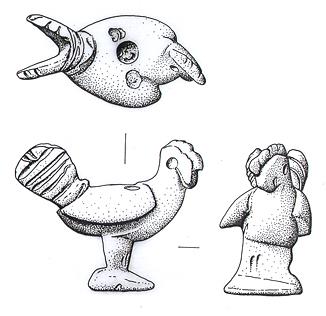

Roman figurine of a rooster. (© NCC and S. White.)

Two Early Saxon inhumation cemeteries have been recorded in Shouldham. The fact that one of them overlies the Roman settlement site (NHER

28645) strongly suggests that it was in an important ceremonial position. The other cemetery (NHER

35988) was identified by the number of brooches, pendants and dress fittings that were found. These items are good indicators of Saxon burials as individuals were often buried in their finest clothes and jewellery. A third much later cemetery (NHER

14177), dating to the Late Saxon/early medieval period, has been identified in Shouldham. This particular site was situated within a large pottery scatter, which may suggest that a settlement was located here during the end of the Saxon period. Several other interesting Saxon small finds have been found in Shouldham including a magnificent gold sword belt mount (NHER

28385), a pendant made from a pierced 4th century Roman coin (NHER

33342) and a cruciform brooch (NHER

35005).

Shouldham appears to have been an attractive location for contemplation and worship during the medieval period. A Gilbertine Priory (NHER 4255) was built to the northeast of the modern village in about 1190 to house a community of monks and nuns. It was dissolved in 1538 and the ruins were removed in part during 1840. The present Abbey Farm house sits over the nave of the Priory church and incorporates several blocks of medieval ashlar. Many earthworks belonging to the Priory lie to the south of the farm building and these consist of quite complex water channels, rectangular enclosures and fishponds. Indeed, many of these features are only visible on the spectacular aerial photographs of the site, as they are difficult to discern at ground level. However, the most striking feature of the Priory is the central north-south channel that neatly divides the site into two roughly equal portions for reasons unknown. As one would expect, a great variety of finds have been recovered from the Priory including medieval stone coffins and medieval page turners. A number of the buildings on Westgate Street also incorporate blocks of medieval stone (NHER 16433). As these buildings date to the 19th century it is possible that these blocks came from the Priory as it was pulled down during this period.

At this time the parish also had two fully operational churches: St Margaret’s (NHER 4290) and All Saints’ (NHER 4365), both of which were mentioned in the Domesday Book. St Margaret’s was still standing in 1519 but fell from use at some time thereafter. In 1840 its ruins were rediscovered after lowering a hill in a field adjoining the All Saints’ Church. Nothing much now remains but various flints and medieval bricks can be seen on a slightly raised ground surface at this location and ploughing has unearthed several human bones. The surviving All Saints’ Church is built from a mixture of carstone and flint. The tower appears to be one of the earliest features, dating to the late 13th/early 14th century and in the Decorated style. The modern appearance of the nave owes much to a restoration in 1870 but this work left the splendid 15th century nave roof intact. This special roof has alternating large and small hammerbeams and features hammerposts bearing carved angels.

Aerial photograph of the earthworks of the shrunken village of Shouldham. (© NCC)

The actual settlement in medieval times lay behind Colt’s Hall (NHER

46925) to the east of the modern village. This deserted medieval settlement (NHER

4283) was discovered in 1970. Investigation of the site in 1974 and 1983 showed very fine earthworks relating to building platforms, enclosures, tofts and a hollow way that ran east to west between the church and Colts Hall. The earthworks were fortunately underneath untouched pastureland and survived in good condition. However, since 2001 they have been subject to a protection agreement to ensure their continued survival. According to the Ordnance Survey, Shouldham had a livestock market twice annually during the medieval period. This site of this so-called ‘Fair Stead Market’ (NHER

18018) has been placed northwest of the village in the plantation of the same name. A full time market was operating in the town by 1334, perhaps explaining why Blomefield's History of Norfolk refers to the town as 'Shouldham Market'.

Fenland fieldwalking and metal detecting have found numerous sherds of pottery and several pieces of metalwork. However, these merit only a brief mention as they tend to be mundane items like coins (NHER 38072), buckles (NHER 35909) and strap ends (NHER 39658). Twenty-two sites with medieval pottery sherds were also recorded (NHER 19592).

In the post medieval period the hilly and windswept landscape of Shouldham was exploited for corn milling. 18th and 19th century maps show two windmills (NHER 14523 and 14524) in the parish and a kiln for lime burning (NHER 14621). An early 19th century tithe map also shows a pottery/brick kiln (NHER 11268) in Shouldham. The manufacture of bricks and the production of flour would have helped to supplement the income the villagers made from farming.

Several of Shouldham’s finer buildings were built during the post medieval period and have been listed as properties of architectural interest. The most impressive of these is Colt’s Hall (NHER 46925), which dates to around 1830. It has a gault brick facade but is otherwise made from reused clunch and carstone. The grand central door is below a seven-vaned fanlight with a roll-moulded timber surround, all within a semi-circular recessed bay. The major post medieval hall, ‘Frog’s Hall’ which was owned by Mr Catton, no longer exists. The site of this hall has been debated but it seems likely that it lies about 50m to the south of a collection of pottery sherds and building remnants located along the Norwich Road (NHER 11267).

The Spar (NHER 46926), which is set along the Green, is also worth a look. This house and shop date to around 1760 but have 20th century alterations including the plate glass shop front. However, perhaps the most interesting structure erected in the post medieval period was a freestone obelisk that was used as a drinking fountain (NHER 4284). It was in existence by 1839 but the exact location has been a matter of debate, with the most likely location being somewhere on Catton’s Plantation.

The most recent archaeological record for Shouldham relates to World War One and World War Two military sites. The RAF base at Marham (NHER 4510) extends into Shouldham parish. The Royal Flying Corps first used this airfield during World War One. The Royal Air Force took over the site during World War Two, at which time it had three Picket Hamilton forts. Readers may also be interested to know that the Cold War Hardened Nuclear Shelters built here in the 1980s are considered to be of national importance.

In 1979 a huge set of earthworks and collection of ruined buildings were reported in Shouldham Warren. The earthworks and buildings probably date to World War Two, and may be the remnants of a shooting range or temporary camp. This constitutes the only definite site from this era, as although the crash site of an aeroplane (NHER 14177) has been reported the actual crash site of the World War Two plane has not been substantiated.

This concludes the overview of the archaeology of Shouldham. Interested readers should access the individual records held for the parish to gain a fuller knowledge of Shouldham’s past.

Thomas Sunley (NLA), 3 May 2007.

Further Reading

Brown, P. (ed.), 1984. The Domesday Book (Chichester, Phillimore & Co.)

Pevsner, N. and Wilson, B. 1999. The Buildings of England, Norfolk 2: North-west and South (London, Penguin)

Rye, J., 1991. A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place Names (Dereham: The Larks Press)

Silvester, R. J., 1991. The Fenland Project Number 3: Norfolk Survey, Marshland & Nar Valley (Gressenhall, Norfolk Archaeological Unit)