This Parish Summary is an overview of the large amount of information held for the parish, and only selected examples of sites and finds in each period are given. It has been beyond the scope of the project to carry out detailed research into the historical background, documents, maps or other sources, but we hope that the Parish Summaries will encourage users to refer to the detailed records, and to consult the bibliographical sources referred to below. Feedback and any corrections are welcomed by email to heritage@norfolk.gov.uk

Brancaster is a large parish on the north Norfolk coast. Located between Titchwell and Burnham Norton the parish includes extensive areas of salt marsh and intertidal mud and sand flats as well as undulating agricultural land further inland. The parish also includes the smaller villages of Burnham Deepdale and Brancaster Staithe. Brancaster derives its name from the 3rd century AD Roman fort Branodunum (NHER 1001). It either comes from Old English meaning broom camp, or is a condensed form of the fort name that derives from Celtic meaning crow fort. The archaeology of the fort is well known but the area also has extensive World War Two defences and evidence for activity at other periods.

The earliest evidence for human activity in the area dates to the prehistoric period. Palaeolithic worked flints including a handaxe (NHER 1732) and an Upper Palaeolithic flint scraper (NHER 1732) have been discovered. Excavations at the Roman settlement site (NHER 1002) near the fort have recovered evidence for earlier activity here including Neolithic pits and a posthole also dating to this period. Elsewhere in the parish there is also evidence for Neolithic activity – several Neolithic flint handaxes (NHER 1361 and 14086), a leaf shaped flint arrowhead (NHER 14375), a flint chisel (NHER 17790) and a flint scraper (NHER 29199) have been recovered. Bronze Age pits have also been uncovered at the Roman settlement site and Barrow Common in the south of the parish may be named after a Bronze Age barrow (NHER 1363). Several possible ploughed out Bronze Age ring ditches (NHER 17235 and 18653) have been identified by the National Mapping Program from aerial photographs. A Middle Bronze Age spearhead (NHER 30123) has been recovered by a metal detectorist. There is also plenty of evidence for the later prehistoric period. The excavations at the Roman settlement site uncovered extensive evidence for Iron Age activity including an enclosure, an inhumation and more pits. A possible Iron Age farmstead (NHER 27060) and associated field system can be seen as cropmarks and there is also evidence for Iron Age occupation (NHER 27066) at another later Roman site in Burnham Deepdale. A relatively rare Late Iron Age silver coin (NHER 1364) has also been recovered.

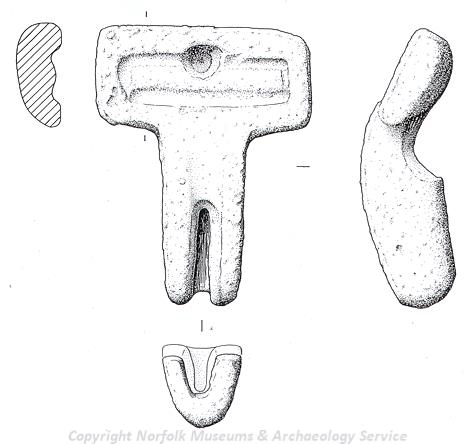

A Roman brooch mould from Brancaster. (©NCC)

The sequence of activity in the Roman period can be cautiously reconstructed. As we have seen there was activity and occupation here already in the Iron Age. An undated early Roman fort (NHER

1004) of playing card shape can be seen on aerial photographs north of Branodunum. It is likely that the Roman civilian settlement or vicus (NHER

1003, 1002 and

1004) grew up around this fort. Branodunum Roman Saxon shore fort (NHER

1001) was built to replace the earlier one between 225 and 250 AD. It was designed to guard against Saxon invaders and is the most northerly of these types of fort in Britain. Excavations from the 1800s to 1985 inside the fort show that it was occupied and in use until the 4th century AD. At the time of the building of the fort or shortly after the vicus outside it was extensively rebuilt and a 3rd or 4th planned settlement can be seen on aerial photographs. There are also numerous other Roman finds from the parish including some Roman skeletons (NHER

1372) from Brancaster Hall and possibly a mosaic (NHER

31152) that was uncovered at the caravan park in the 1960s and then covered back up again. There are also more ephemeral remains such as the probable Roman occupation cropmarks (NHER 27066 and

26795) recorded by the National Mapping Program and vague reports of a hoard of Roman coins (NHER

1370) being found in the parish around 1600.

There is much less evidence for activity in the Saxon period, although finds of Early Saxon pottery, a comb and a brooch from the vicus (NHER 1002 and 1003) may indicate that for some time there was continued occupation here. Late Saxon pottery (NHER 12700 and 15317) has been found elsewhere in the parish and a Saxon coin (NHER 18509) of Eadgar (AD 959 to 975) was found on the golf course. There was probably a Late Saxon church on the site of St Mary’s in Brancaster (NHER 1390). St Mary’s, Burnham Deepdale (NHER 1733) still has a Late Saxon tower that was built between 1050 and 1100. The church also contains a lovely Norman font depicting the months of the year. It is possible that the farmstead identified by the National Mapping Program may be a Saxon farm (NHER 27060).

Burnham Deepdale Church, view of the chancel, showing the Late Saxon round tower and the south porch. (©NCC)

By the medieval period the centres of occupation at Brancaster, Brancaster Staithe and Burnham Deepdale were settled. The earlier church at Brancaster was replaced with a 12th century one, parts of which still survive. There are marks of medieval ridge and furrow (NHER

11586 and

26756) and field systems (NHER

26993,

26995 and

27068) visible on aerial photographs. The identification of possible medieval oyster beds (NHER

27063) demonstrates the importance of the sea as a resource. Scatters of medieval pottery (NHER 15317,

37375 and

40262) and metal finds, including a medieval dagger pommel (NHER

35644), are testament to continued activity in the area.

The Old Maltings, Brancaster. (©NCC)

During the post medieval period reclamation of the salt marshes began and a series of earthwork banks and ditches (NHER

26771,

26777 and

26794) were cut to drain the marshland for agriculture. The sea continued to be used as a resource and shellfish pits (NHER

26767 and

26768) were dug but the sea was also seen as a threat and sea defences (NHER

26670 and

26675) were built. The largest malt house (NHER

1377) in Britain was built in 1747 in Brancaster Staithe with Roman building material from the fort, but was demolished in the early 19th century. Other buildings were also built using material from the fort walls that were destroyed in the 18th century. Dial House (NHER

18216) was formerly the Victory pub and had its own brew house. Although the building dates to the early 17th century renovations and extensions including Roman material were added in the 18th century. The house is now owned by the National Trust.

Dial House, Brancaster. (©NCC)

Town Farm House (NHER

18217) and Staithe House (NHER

18218), large and grand houses, date to this period and demonstrate the wealth of some in the area. These buildings are now protected as Listed Buildings. Other buildings have been less fortunate. Brancaster’s two windmills (NHER

15006) have been dismantled and the post medieval lime kiln (NHER

15834), which was used by Henry Smith until World War Two, has been demolished.

World War Two battery at Brancaster, the best preserved coastal battery of its date in Norfolk. (©NCC)

Brancaster’s archaeology extends to the modern period. There are extensive defensive structures around the coast centred on the Royal West Norfolk Golf Clubhouse. These include pillboxes (NHER

15653,

15654 and

30299), a rare coastal battery (NHER

31113), a radar station (NHER

31786) and anti tank structures (NHER

18220 and

26787). It appears that training also took place here as a slit trench (NHER

27062) and many bomb craters (NHER

26653) created during practice exercises can be seen on aerial photographs. As well as these military monuments Brancaster also boasts Norfolk’s oldest motoring telephone box (NHER

33409) – a yellow and black phone box dating to before the 1950s. The parish contains a wide range of archaeology from a variety of periods. From the earliest activity at Iron Age occupation sites and the presence of the Roman forts in the area to the modern ruins of World War Two defences and training there is plenty of evidence for the changing human uses of the landscape.

The oldest AA telephone box in Norfolk is situated just off the A149 in Brancaster. (©NCC)

Megan Dennis (NLA), 10th October 2005.

Further Reading

Brown, P. (ed.), 1984. Domesday Book, 33 Norfolk, Part I and Part II (Chichester, Philimore).

Knott, S., 2005. ‘St Mary, Brancaster’. Available:

http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/brancaster/brancaster.htm. Accessed 26 January 2006.

Knott, S., 2005. ‘St Mary, Burnham Deepdale’. Available:

http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/burnhamdeepdale/burnhamdeepdale.htm. Accessed 26 January 2006.

Langley, C. and Smith, L., 2003 ‘Roll of Honour – Norfolk – Brancaster’. Available:

http://www.roll-of-honour.com/Norfolk/Brancaster.html. Accessed 26 January 2006.

Mills, A.D., 1998. Dictionary of English Place Names (Oxford, Oxford University Press)

National Trust, 2005. ‘National Trust Brancaster’. Available:

http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/main/w-vh/w-visits/w-findaplace/w-brancaster.htm. Accessed 26 January 2006.

Rye, J., 2000. A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place-names (Dereham, The Larks Press).

Unknown, 2006. ‘BRANODVNVM’. Available:

http://www.roman-britain.org/places/branodunum.htm. Accessed 26 January 2006.