This Parish Summary is an overview of the large amount of information held for the parish, and only selected examples of sites and finds in each period are given. It has been beyond the scope of the project to carry out detailed research into the historical background, documents, maps or other sources, but we hope that the Parish Summaries will encourage users to refer to the detailed records, and to consult the bibliographical sources referred to below. Feedback and any corrections are welcomed by email to heritage@norfolk.gov.uk

The name ‘Oxborough’ is derived from the Old English for a fortified place frequented by oxen. The parish is part of the Breckland local government district, and was enlarged by the abolition of Caldecote civil parish in 1935, an area of 700 acres which makes up the north of the modern day parish. Along the northwestern border runs Oxborough Wood, which includes a nature reserve at its most southerly tip. The parish is bordered to the south by the River Wissey, and to the north by Caldecote Fen and Fen Wood. Oxborough parish contains the village of that name and the remains of Caldecote village, as well as the area to the southwest which is referred to as Oxborough Hythe.

Evidence of occupation, or at least seasonal exploitation, has been recovered for periods from the prehistoric onwards. Numerous examples of individual worked flints such as axeheads (NHER 2604), hammerstones (NHER 4793), and daggers (NHER 14840) have all been found, as well as areas of burnt flints (NHER 4586), which indicate domestic activity. The densest activity can be seen in the southwestern part of the parish, where three of the greatest concentrations have been recovered, on or near the floodplain of the River Wissey (NHER 32828, NHER 32830, NHER 40844).

A Bronze Age dirk from Oxborough. (© NCC)

Whilst evidence of early prehistoric activity is not particularly dense, possible Bronze Age sites are more numerous. A number of undated ring ditches are scattered across the parish, and some or all of these may be attributable to the Bronze Age (NHER

15132, NHER

15134, NHER

15138). One site that has been confirmed as Bronze Age is a barrow located in the southeasterly corner of the parish, which also shows later reuse during the Saxon period (NHER

25458). Objects of the Bronze Age are reasonably common, and include a number of palstaves (NHER

2617, NHER

2618) and axeheads (NHER

4793, NHER

22984), as well as a hoard of nineteen spearheads (NHER

2615). The most stunning and almost unique find has been a complete ceremonial dirk, recovered in My Lord’s Wood just north of the River Wissey (NHER

29157).

Iron Age activity is harder to trace, and there are no monuments in this parish that have been confirmed to date from this period. Iron Age pottery, personal adornments and coins have been recovered north of Caldecote Farm (NHER 1021), in association with a large number of objects from the prehistoric to post medieval periods, which may indicate occupation on this site at least periodically throughout human history in this area. Iron Age objects have been found sporadically in other areas (NHER 33549, NHER 33538), but this site has an unrivalled density of evidence.

Indeed, during the 19th century this site (NHER 1021) was initially interpreted as a Roman cemetery, due to the large numbers of Roman pottery sherds recovered. This may be correct, but with the more recent recovery of roof tiles, furniture fittings, vessels and toilet articles, it seems likely that at least part of this large site was also occupied by the living. Two kilometres to the east (NHER 24053, NHER 28671) building materials, tiles and opus signinum, as well as personal objects and fine pottery have been recovered, suggesting the presence of one or more Roman buildings. Aerial photographs of the area (NHER 36697) have documented cropmarks that indicate a villa complex may have been present at some point during the Roman period.

Although many objects have been recovered at both of these potential occupation sites, considerably more have been found across the parish. These finds commonly include pottery sherds (NHER 17686, NHER 21086), brooches (NHER 20169), and coins (NHER 20172, NHER 23506). Of particular interest is the recovery of a Roman votive axe (NHER 20175), a miniature copper alloy weapon probably deposited as a gift to one or more deities.

Interestingly, both of the potential Roman villa areas show continued use into the Saxon period. In the case of the site near Caldecote Farm (NHER 1021), the finds are largely personal ornaments or dress fittings, with some pottery sherds. On the north side of the road which borders the more easterly villa site (NHER 24053, NHER 36697, NHER 17686) large concentrations of Anglo Saxon metal objects have been recovered, indicating the presence of an Anglo Saxon cemetery close to, or in the grounds of, the Roman villa (NHER 34131). Both sites appear to be predominantly from the Early Saxon period.

Two hundred metres northeast lies another Early Saxon cemetery (NHER 34355, NHER 25458), this time reusing a Bronze Age burial site. Just 400 metres to the north of that lies yet another Early Saxon cemetery. All of these sites have been identified on the basis of the very high concentrations of ornamental metal objects recovered from the areas. Although they are all listed as separate sites, their close proximity to each other is suggestive that they may represent a single, if widely distributed burial site, or perhaps several areas of Early Saxon use, one or more of which may be a cemetery.

Objects from the Early Saxon period are most common, but there have been small numbers of Middle and Late Saxon period objects recovered from other areas (NHER 23520), including a few horse trappings (NHER 23506). It should be noted that at the time of the Domesday Book the parish was considered to be of average value, and contained two mills and one fishery by this point, although there is no mention of a church. Caldecote, a separate parish at this time, was of considerably less size and value, and again apparently without a church. However the remains of St Mary’s Church, Caldecote (NHER 2619), a medieval church associated with the now deserted village, still remain, though they are too poor to be dated.

The village itself (NHER 2634) is just south of Caldecote Farm, and is thought to have been in decline by the mid 15th century, becoming completely deserted by the 16th century. All that remains today are two fields containing scattered debris of masonry buildings, and one which retained crofts, ridge and furrow ploughing evidence and a street until it was affected by modern farming activities. Another deserted settlement has been suggested on land just south of Oxborough village, but no evidence has been seen on aerial photography and the possibility seems doubtful.

Amongst the medieval buildings of Oxborough there are a number that survive only in record, including a 13th century leper hospital (NHER 12389), an unidentified guildhall (NHER 21985), and the site of the guildhall of Corpus Christi (NHER 21986). A surviving set of fishponds has also been identified (NHER 33611), and these may be the ones mentioned in the Domesday Book. In addition to monuments, large numbers of medieval objects have been recovered, most commonly coins (NHER 20172), personal or horse ornaments (NHER 32085), furniture or book fittings (NHER 34688) and pottery sherds (NHER 2621). Some of the most interesting pieces include a complete medieval ampulla of 12th to 14th century date (NHER 32985), a possible Papal Bull (NHER 20168), and an early medieval silver ring brooch (NHER 22096).

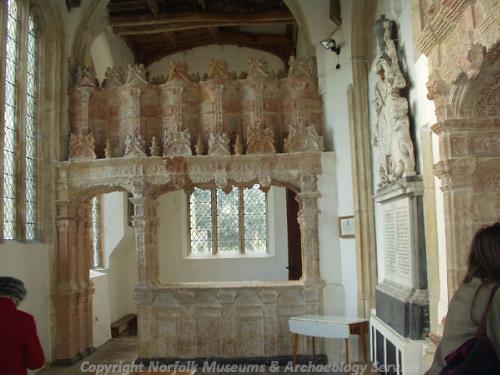

Terracotta screen, Oxborough Church. (© NCC)

In contrast to Caldecote, Oxborough village thrived during the medieval period, and the grade I listed church of St John the Evangelist (NHER

2642) is still in use today, despite losing its roof in 1948. Worship now takes place in the attached chancel, as the collapse of the large tower destroyed the nave roof. Highly picturesque, the walls of the church remain in place, their floors covered in green turf and open to the heavens. Luckily enough, the chancel also shelters some of the finest terracotta tombs and tombstones in England, examples of the peak of Catholic art on the eve of the Reformation.

Although established in the medieval period, the earliest remaining part of St John’s Church is the west window of the north aisle, which dates back to the 14th century. The Bedingfeld family, who were the sole owners of the parish from at least the mid 15th century, established the chantry chapel in 1496. Just fourteen years previously, Sir Henry Bedingfeld had obtained a licence from Edward IV to fortify Oxborough Hall (NHER 2627), a little late as the building work on the massive moated house had already started.

Oxburgh hall front elevation. (© NCC)

Oxborough Hall (NHER

2627) is a large square mansion house surrounding a courtyard, and retains a tremendous 15th century gatehouse approached over a closely pressed moat, flanked on either side by two seven-storey high octagonal towers. A staunch Catholic, Sir Henry Bedingfeld had been instrumental in placing Mary Tudor on the throne, and was governor of the Tower of London whilst Elizabeth was held there. Elizabeth appears to have held him no ill will despite his role as her gaoler, granting him the manor of Caldecote as reward for his service to her. Indeed it may have been this grant, putting Caldecote second to Oxborough in its lord’s favour, which paved the way for the final desertion of Caldecote village and the abandonment of St Mary’s Chapel.

However, both the family’s continued devotion to the Catholic faith, and their proactive support for the royal line during the Commonwealth damaged their fortune. As a result, the structure of Oxborough Hall has remained quintessentially Tudor, whilst many of the Bedingfeld’s peers continued to alter their stately homes with every changing fashion. No significant construction work took place until the hall range south of the gatehouse was pulled down in 1775. Fortunately it was rebuilt in the massive renovation work of the Victorian period, when the architects Pugin and Buckler gave the hall interior its current layout and were responsible for current romantic Gothic style exterior that represented the height of 18th century fashion. Although Oxborough Hall is now the property of the National Trust, the Bedingfelds remain in occupation, and their public support for the royal line continues, with Henry Paston-Bedingfeld currently holding the position of Her Majesty’s York Herald of Arms in Ordinary.

The parish also contains a number of other listed late medieval and post medieval buildings, including Chantry Cottages, dating to as early as 1483 (NHER 2641), the ruins of St Mary Magdalen’s Church (NHER 2628) near the Old Rectory, White House Farmhouse, a timber framed building dating to around 1600 (NHER 21995), as well as Oxborough Park, a tract of land massively extended in the 19th century and laid out around 1845 in a design of D'Argenville's 'Theorie' (NHER 30479). A number of coins and metal objects have also been found (NHER 39935), including a 15th or 16th century animal headed tap (NHER 25825) and a 16th or 17th century gold posy ring (NHER 40545), though post medieval objects from Oxborough are not as numerous as one might expect.

The remains of a number of later buildings also remain, including a disused pumping station (NHER 4796), Oxborough Watermill (NHER 14525), and a 19th century road bridge (NHER 46204), the later listed as a Scheduled Monument. Also listed is an interesting two-storey brick lodge located in the south of Oxborough village and dating to around 1830, possessing a pair of polygonal angle turrets and a statue in the niche above the central doorway (NHER 46206). There remains only one site constructed in the modern period, a probable World War One searchlight battery operative in 1918 just east of Caldecote fen (NHER 12417).

As we have seen, evidence for human exploitation and occupation of the parish of Oxborough dates from the prehistoric period right up to the current day. Confirmed Bronze or Iron Age evidence is scarce, but this may be altered in the future if some of the relatively high numbers of ring ditches are dated. Of particular interest is the possible existence of two Roman villa sites (NHER 1021, NHER 24053, NHER 28671), as well as the large scattered Early Saxon cemetery site (NHER 24053, NHER 36697, NHER 17686, NHER 34355, NHER 25458). However, by the late medieval period the parishes of Oxborough and Caldecote have both become dominated by the fortunes of the Bedingfeld family, and the development of Oxborough parish and village owes a lot to the building of the stunning moated Oxborough Hall (NHER 2627).

Ruth Fillery-Travis (NLA), 24 November 2006.

Further Reading

Knott, S., 2006. ‘St John, Oxborough’. Available:

http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/oxboroughcofe/oxboroughcofe.htm. Accessed 24 November 2006

Knott, S., 2006 ‘Oxburgh Hall chapel of St Margaret and Our Lady, Oxborough’. Available:

http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/oxboroughhall/oxboroughhall.htm. Accessed 24 Novemeber 2006

Morris, J. (General Editor), 1984. 'Domesday Book, 33 Norfolk, Part I and Part II' (Chichester, Phillimore & Co)

Rye, J., 1991. A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place Names (Dereham, The Larks Press)

Southall, H., 2006 ‘A Vision of Britain Through Time: Oxborough CP’. Available:

http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/relationships.jsp?u_id=10208749. Accessed: 24 Novemember 2006

Weikel, A., 2004. ‘Bedingfeld , Sir Henry (1509x11-1583)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford, Oxford University Press)